3 things to look out for in next week’s inflation report

With no major changes expected at this week’s monetary policy committee meeting, eyes are already turning to next week’s inflation report by the Bank of England.

Here’s what to look for.

1. Forward guidance will disengage from unemployment

Bank governor Mark Carney’s comments at Davos suggest that the Bank is backing away from its seven per cent unemployment threshold. The Bank originally forecast that this would be reached in 2016, but the rate of joblessness is hovering only 0.1 percentage points above the threshold.

Berenberg’s Robert Wood is unimpressed with suggestions that the terms of guidance could be altered:

The point of guidance is to give more clarity about how policy is set. Changing guidance so soon, or switching to an alternative threshold variable, reduces clarity. Indeed, the big cost may be that future Bank announcements carry much less credibility.

Speeches by both Carney and monetary policy committee member Paul Fisher suggest that the Bank may augment forward guidance with a wage or productivity threshold, giving policymakers more flexibility to keep rates low for some time yet.

2. Inflation projections cut

While it’s now well understood that the Bank’s unemployment forecasts were way off base, it’s less well understood that they were also not expecting inflation to fall so quickly.

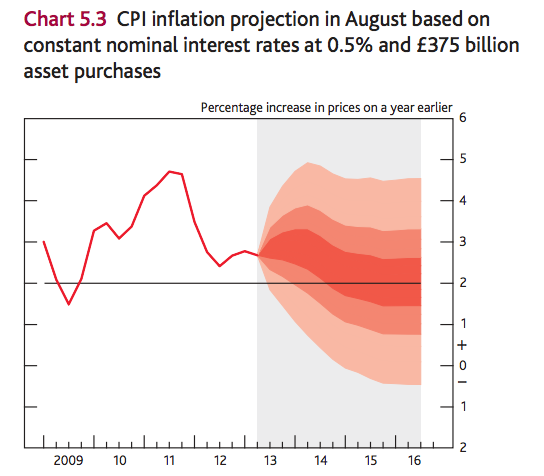

CPI fell back to target in December, which the Bank hadn’t projected would happen until after the end of 2016 if rates were held at 0.5 per cent.

Martin Beck of Capital Economics said:

The Committee is likely to revise down its near-term inflation forecast in February’s Inflation Report. January’s further rise in sterling provides another reason to expect this. And despite the pace of the fall in joblessness, pay growth shows no signs of taking off.

3. A major reassessment of the labour market

The Bank’s estimates for unemployment were not just wrong, they were way out.

In August, the Bank described the labour market:

Unemployment rate edging down, but likely to remain above 7.5% in 2013.

In November, it revised its view, cautiously saying that the rate had “fallen by a little more than anticipated”. But even as those words were printed, unemployment had plunged to 7.1 per cent.

This suggests a major issue with the Bank’s understanding of the market which might deserve a deeper reassessment.

The MPC minutes in January suggested this might be underway:

Shifts in the composition of unemployment had suggested that equilibrium unemployment might be lower than previously thought. In particular, most of the fall in unemployment in the three months to October had come from falls in medium and long-term unemployment. Higher transition rates out of longer-term unemployment had suggested that those affected might have retained a greater attachment to the labour market than had been feared.

This could indicate a simple cut in the unemployment threshold, but there’s an outside chance that the Bank will announce bigger changes to its understanding of the labour market.