The Super League was a bungled sales pitch from start to finish

It could have been a news story tailor-made for the short attention span of the 2020s: the Super League, a football competition intended to rival or replace the UEFA Champions League at the summit of the European game, was announced last week. It floundered for a moment, before falling into abeyance in a shorter time than the Ever Given was stuck in the Suez Canal. We read analysis of the concept, understood its dynamics, assessed its strengths and weaknesses and wrote its obituaries all in a matter of days.

I am not a football devotee. But I do know public policy works and how you sell (or fail to sell) a product. The attempt to form the European Superleague was a bungled mission from start to finish.

The announcement of the ESL lacked a coherent communications strategy. There was no attractive or authoritative voice on the airwaves to make the championship’s case and extol its virtues. The president of Real Madrid, Florentino Pérez, was named chairman of the ESL; but a dry, seventy-something Spanish billionaire was never going to be the box office which the league’s ambitions deserve. Where was Gary Lineker, Thierry Henry or Gianluca Vialli to put a reassuring arm around the shoulders of uneasy fans?

The lack of coherence went deeper. The clubs involved have different traditions and ownership: Manchester United, Arsenal and Liverpool are owned by hungry corporate American ‘sportspreneurs’; Manchester City is the ornament of the deep-pocketed Abu Dhabis and Inter Milan of Chinese interests; while Juventus and Spurs remain more anchored in their historical patterns of ownership. This diversity meant that the motivation of the clubs varied. Some are heavily in debt and need to squeeze their income streams, some exist as passion projects which need only wash their faces, while others still are trophies which are, in balance sheet terms, purely outgoings.

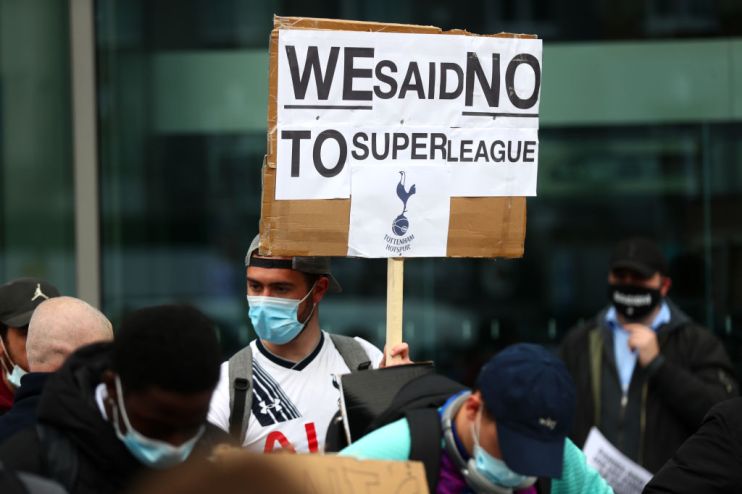

The political reaction to the creation of the new league was swift and fierce. Drawing on the anger of fans, Boris Johnson and Emmanuel Macron were quick out of the traps to condemn the ESL, the former calling it “very damaging for football”. The Spanish and Italian governments weighed in to defend the existing rights and privileges of UEFA. No one, it seemed, was in the mood for a revolution. The barricades were manned, but in the cause of the establishment.

The Super League was left without the heft or the agility to respond to a landscape much more hostile than it might have expected. After some curious inquiries, reporters discovered that public relations for the new championship were in the hands of Whitehall veterans inHouse Communications. The company is headed by Jo Tanner and Katie Perrior, both wise in the ways of the UK political jungle—Katie was director of communications for Theresa May in Downing Street—but had been contracted only hours before the ESL project was launched. They were left scrabbling for grip and it showed. Even hardened campaigners could only do so much without a strategy or a vision: and the ESL seemed to offer neither.

Success has many parents, but failure is an orphan, and the Super League has rapidly taken on the whiff of the orphanage. After the English clubs withdrew one by one from the doomed operation, JP Morgan, the bank which had agreed to provide finance, pasted on the more-in-sorrow-than-in-anger faces and issued a plangent statement: “We clearly misjudged how this deal would be viewed by the wider football community and how it might impact them in the future. We will learn from this.”

A nonsense, of course: there can be no learning without a clear-eyed assessment of what went wrong, and an honest reflection would be that JP Morgan had backed a promising but doomed project, and now had burned fingertips. It happens. But there must be corporate schmalz.

The Super League is dead now. What have we learned? It was a superficially profitable but badly conceived project which had no coherent narrative, no unifying purpose, and a lack of authoritative advice. It was led by money, not in itself a mortal sin but raised above the venial by shoddy planning. Football fans have triumphed, for the moment, and the phrase “lessons learned” is scattered around like confetti. It will be instructive to see who learns, what, and how.