Why it will take real bank reform to rid us of our addiction to candy floss credit

GROWTH is back. Unemployment is falling. Each week seems to bring a flurry of upgraded forecasts. The mood of the pundits has gone from gloom to boom.

But headline growth figures do not tell the full story. They only tell us about headline growth. Any government can raise output – and all other kinds of economic indices – by hosing cheap credit at the economy. As successive British chancellors have discovered, it is not quite the same thing as sustainable growth.

The signs are that we are in the early stages of yet another credit-induced boom. Even at this early stage of the “recovery”, we are more dependent on consumer spending and mortgage debt than before. The current account deficit – a good indicator of excessive demand – has deteriorated from 1 per cent of GDP in 2009 to approaching 4 per cent in 2013.

The savings rate has fallen. Britain now invests – in the correct sense of the term – a smaller share of her national income than 158 other countries.

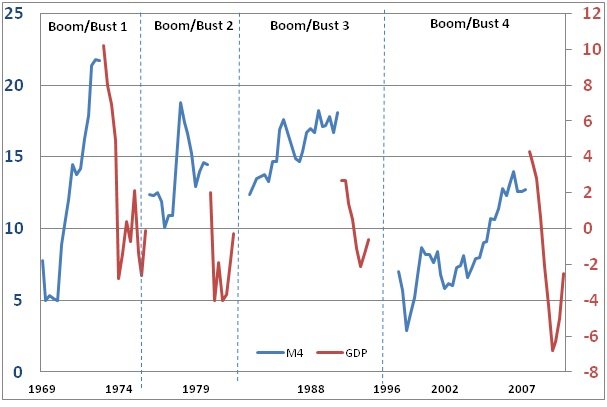

Since 1971, Britain has experienced four periods of sustained economic downturn. Each time, the fall in output was preceded by the same thing: a credit-induced boom. The same familiar pattern is happening again, I fear.

“Not so!” I hear you say. “Money measures aren’t growing wildly. M4 is under control. Thanks to Bank of England ‘forward guidance’, there’s no chance of repeating the mistakes of the past.”

True, M4 has not expanded wildly. But M4 does not tell us the whole story.

Look instead at the Divisia index, which measures not only broad money, but the ease with which it can be spent. Divisia is considered by many to be a better indicator of likely future spending. A canary in the monetary mine shaft, Divisia suggests we are headed straight into the familiar boom/bust credit cycle.

As for the notion that those wise experts at the Bank of England might use “forward guidance” to avoid the mistakes of the past, they cannot even forecast unemployment with any accuracy. It was only five months ago that our central bank bureaucrats confidently told us that unemployment would fall to its present level by 2016.

Appointing Canadian central bankers and hoping they manage interest rates better is not enough.

We need a tighter monetary policy – higher interest rates and an end to QE. If this flies in the face of conventional wisdom, remember that it was such wisdom that got us where we are. Years of gouging on a diet of cheap credit has clogged up our economy’s arteries with “malinvestment”.

M4 lending has outstripped M4 bank liabilities by around £400bn. Mortgage lending dwarfs lending to business, with bricks and mortar soaking up enormous amounts of credit.

After years of candy floss credit, an estimated one in ten British firms is a “zombie” company, capable of servicing its debts but not repay them. Undead, they can carry on doing what they do, but not expand into new markets or innovate. Might this help explain our poor export and productivity performance?

Raising interest rates would flush out the malinvestment. It would encourage savers. Debts would be paid down – or written off. We might at last live within our means.

Most important of all, we need real bank reform.

The monetary regime we have in place today has produced low(er) inflation. But inflation stability on one side of the equation has come with wild credit crunches and banking bubbles on the other. As long as banks are able to conjure credit out of thin air, we run the risk of credit bubbles.

How much a bank lends today depends on its appetite to lend, borrowers’ appetite to borrow – and regulators’ capital ratio requirements. To avoid credit bubbles, how much a bank lends ought to be a function of its deposits, in addition.

In my paper, published by Politeia, I propose a clear legal distinction between money paid into a bank as a loan – against which banks might extend credit – and money paid into deposit accounts, for safekeeping. Rather than a vertical separation between retail and institutional banking, I suggest a horizontal one within banks, with two tier accounts, rather like there used to be with building societies.

If customers placed more money into loan accounts relative to deposit accounts, the ability of the bank to extend credit would grow. Conversely, if customers shifted money into deposit accounts, the ability of the bank to create credit from nothing would be curtailed.

Douglas Carswell is Conservative MP for Clacton. His paper, After Osbrown, is published by Politeia.