The rise and fall of 20th Century monetarism, according to one of Margaret Thatcher’s advisors

The Bank of England has faced a lot of criticism over the past few years for failing to pay sufficient attention to the money supply.

Earlier this month, Mervyn King – a former Bank Governor – said it was “foolish” for central banks to have relied on forecasting models that ignored the role of money.

It was surely not a coincidence that the Bank included a sizeable segment on the money supply in its latest set of economic forecasts.

With the money supply coming back into prominence, its interesting to look back at a time when monetary aggregates were at the front and centre of the political debate.

Tim Lankester, Margaret Thatcher’s first private secretary for economic affairs, is well placed to do that. His new book, Inside Thatcher’s Monetarist Experiment, charts the rise and fall of monetarism in the late 20th Century.

Monetarism is a school of thought which suggests that a government’s primary macroeconomic objective is to control the growth of the money supply. Monetarists argue that changes to the money supply have a direct link to prices in an economy, making monetary management the most effective way to fight inflation.

The money supply is a simple concept. It measures the sum total of all the currency and liquid assets in a country’s economy. In practice, if the money supply is growing too fast, then the Bank of England should hike interest rates and stop printing money to finance government spending.

The theory was particularly attractive at a time when inflation was regularly running into double digits. Milton Friedman, monetarism’s most prominent advocate, said “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”.

Lankester was never a believer in the monetarist experiment. Yet he found himself having to deliver on a policy which, by his own estimates, ended up putting half a million people out of a job unnecessarily.

“There’s not much in economics that is strictly scientific. Milton Friedman said this (monetarism) was a science and Margaret Thatcher sort of bought into that idea,” he told City A.M.

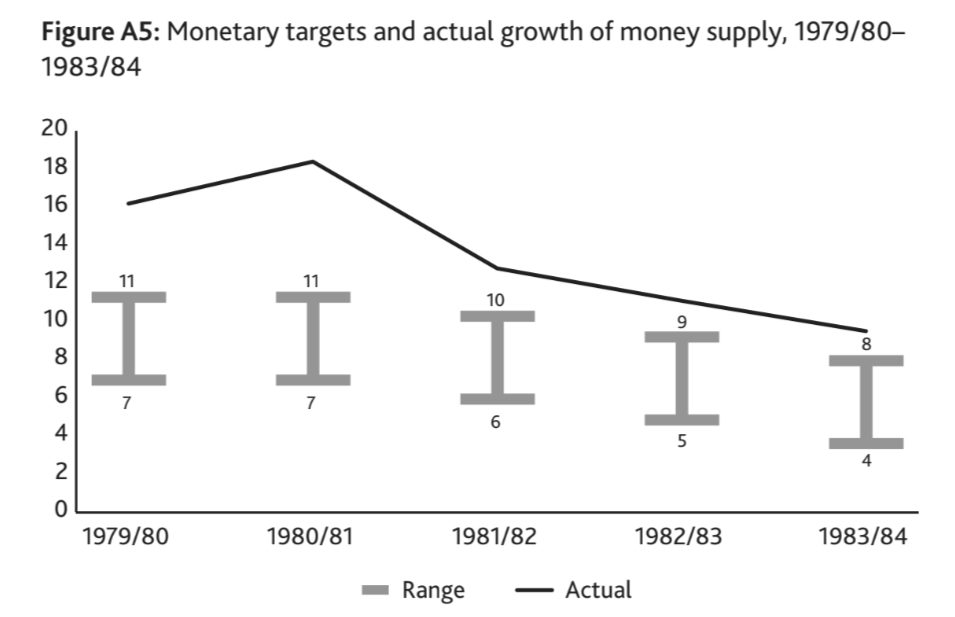

In the early years of the Thatcher government, controlling the money supply became the “single tool” for regulating the economy. Targets for money growth were published. More often than not, they were missed. All the while inflation remained stubbornly high while unemployment steadily grew.

Inflation did eventually get back under control, but this was not due to reduced money growth, which remained above the government’s targets throughout the period. Instead it was due to tight monetary conditions and a substantial fiscal tightening.

“These caused a sizeable fall in national output, especially in manufacturing, and greatly increased unemployment,” Lankester writes, describing it as “one of the most unsatisfactory episodes of economic policy making of modern times”.

Lankester identifies two major problems with monetarism. First, measuring the amount of money in an economy was extremely difficult. Secondly, there was no simple and direct link between the money supply and prices, particularly over the short term.

“Monetarism wasn’t science. It was a proposition which actually wasn’t particularly well supported by the empirics nor by law or theory,” Lankester said.

“There has to be a relationship between the amount of money – however you defined it – and national income, but certainly not on a on a year to year basis,” he added.

So why did it become so popular?

During the course of the 1970s it became clear that the existing Keynesian models were breaking down. Stagflation – the coincidence of high inflation and high unemployment – could not easily be explained by a Keynesian understanding of the economy.

Economists, politicians and financiers were all looking for a different way of understanding the economy The simplicity of monetarism made it an attractive alternative.

But Lankester argued the monetarist conclusion was the wrong one to draw. “Keynesian theory broke down because the natural rate of unemployment – that’s to say the rate of unemployment at which inflation can be expected to stabilise – was going up and up due to the increasing power of the trade unions,” he said.

“If we understood that unemployment was rising along with inflation because of the power of the trade union, I think we wouldn’t have got hooked on monetarism so easily”.

After the 1981 budget, in which Geoffrey Howe raised taxes and cut government spending in the face of deep recession, Thatcher faced growing discontent both in the press and among her own party.

She still believed in the importance of monetary aggregates, but “realised that it was all rather more complicated and difficult than she had earlier imagined”.

Slowly, monetarism fell off the political agenda. Exchange-rate targeting became the dominant policy in trying to control inflation before policymakers eventually settled on a direct inflation target.

In many recent Monetary Policy Reports (although not the latest one) the Bank of England did not even feel the need to mention changes in monetary aggregates. Despite his criticism of monetarism, Lankester suggests this might be too extreme.

“I think the swing against the money supply has gone too far,” he said, although he stressed that the recent bout of inflation was not a result of quantitative easing.

“You can’t ignore the liquidity in the economy…But I don’t believe that the overall liquidity or the money supply determines the level of spending in the economy,” he said.

He noted that with inflation set to fall back to target, unemployment low and the economy showing some signs of growth, the Bank of England “hasn’t done a bad job”.