Inflation ahead of expectations in blow for June interest rate cut hopes

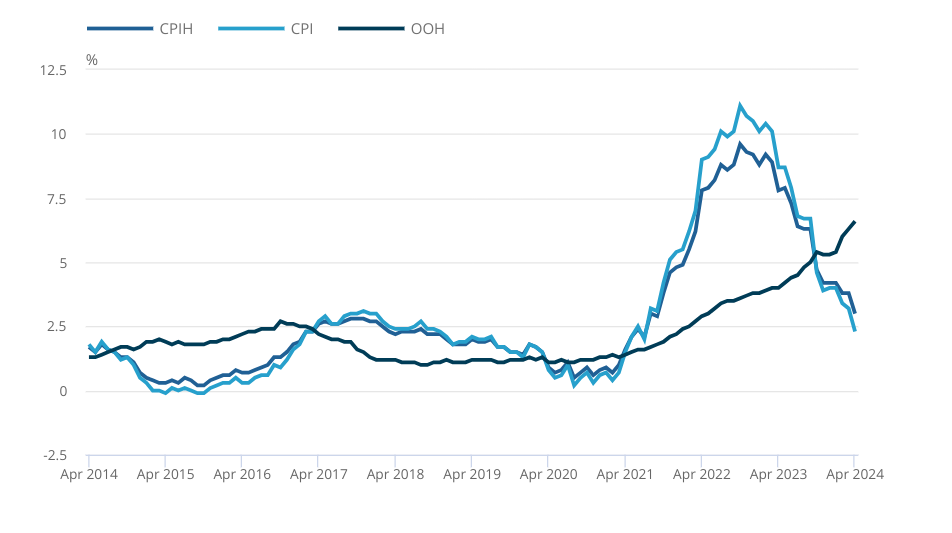

Inflation fell to its lowest level since July 2021 on the back of falling energy prices, but still came in ahead of expectations, reducing the chance of a June interest rate cut.

Prices rose 2.3 per cent in the year to April, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), down from 3.2 per cent in March.

The Bank of England and City economists had expected inflation to fall to 2.1 per cent.

Core inflation, which strips out volatile components such as food and energy, fell to 3.9, down from 4.2 per cent previously but ahead of the 3.6 per cent expected by economists.

“There was another large fall in annual inflation led by lower electricity and gas prices, due to the reduction in the Ofgem energy price cap,” ONS Chief Economist Grant Fitzner said.

“Food price inflation saw further falls over the year. These falls were partially offset by a small uptick in petrol prices,” Fitzner said.

The figures showed that electricity and gas prices fell by 27.1 per cent in the year to April, the largest fall on record. This came thanks to the lowering in Ofgem’s energy prices cap at the start of April.

Food and drink prices meanwhile rose 2.9 per cent, the lowest rate of inflation since November 2021. Food inflation peaked at over 19 per cent in March 2023.

The figures will dent hopes that the Bank of England is on track to cut interest rates as soon as June. The pound jumped to its highest level since March at $1.276 while while traders are now pricing in just a 12 per cent chance of a June rate cut.

At the Bank’s last meeting earlier this month, policymakers confirmed that they were considering cutting interest rates. “A change in Bank Rate in June is neither ruled out nor a fait accompli,” Andrew Bailey said.

Speaking earlier this week, Ben Broadbent, a deputy governor at the Bank, said summer interest rate cuts were “possible” if incoming data aligned with the Bank’s forecasts.

Although inflation has fallen dramatically from its peak of over 11 per cent in October 2022, rate-setters are looking for signs that persistent price pressures are decisively easing.

The Bank has identified services inflation and developments in the labour market, such as unemployment and wage growth, as crucial indicators of inflationary persistence.

On these measures there has been little progress over the past couple of months. Services inflation only fell to 5.9 per cent in April, down from 6.0 per cent in March. The Bank of England had expected services inflation to fall to 5.5 per cent.

Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics, said the services inflation data suggests “the persistence in domestic inflation is fading even slower than the Bank of England had assumed”.

Figures on the labour market, released last week, also came in slightly hotter than expected, with wage growth barely moving in the first quarter of the year.

Yael Selfin, chief economist at KPMG UK said that with wage growth still running hot and economic momentum picking up, the MPC’s “more cautious” members may not be convinced by a June interest rate cut.

A key focus for policymakers going forward is the extent to which firms pass on higher labour costs to consumers. Surveys suggest firms are less able to pass on costs, which could limit the inflationary impact of higher wages.