How mainstream vaccines could soon become too expensive for lots of countries

The poorest countries are the biggest victims of life-threatening diseases, but they are also the ones that could soon no longer afford the vaccines needed to protect them.

The cost of immunising children against a host of deadly diseases is rising fast, and some economies are struggling to keep up.

In fact, over the past 14 years there has been a 68-fold increase in prices, which is “prohibitively high” according to the medical charity Medicins Sans Frontieres.

A spokesperson told the BBC that the constantly rising prices were “calling into question the sustainability of immunisation programmes”.

In 2001, the global cost of vaccinating one child against tuberculosis, measles, diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough and polio was $0.67 (£0.44). By 2014 it had jumped to $45.59 (£30.07).

The report, called “The Right Shot”, says western pharmaceutical companies are now charging much larger sums. According to those in the industry, this change is needed to make up for an increase in manufacture costs for a larger number of vaccines.

Since 2001, rubella, hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenza type b, pneumococcal diseases, rotavirus and the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines have been added to vaccination programmes.

The relatively new pneumococcal vaccine is a particularly expensive one, accounting for 45 per cent of a child's vaccination programme in the poorest countries.

The change in cost means that full immunisation could soon end in some parts of the world, allowing diseases to propagate through populations.

"The price to fully vaccinate a child is 68 times more expensive than it was just over a decade ago, mainly because a handful of big pharmaceutical companies are overcharging donors and developing countries for vaccines that already earn them billions of dollars in wealthy countries,” Rohit Malpani from MSF told the BBC.

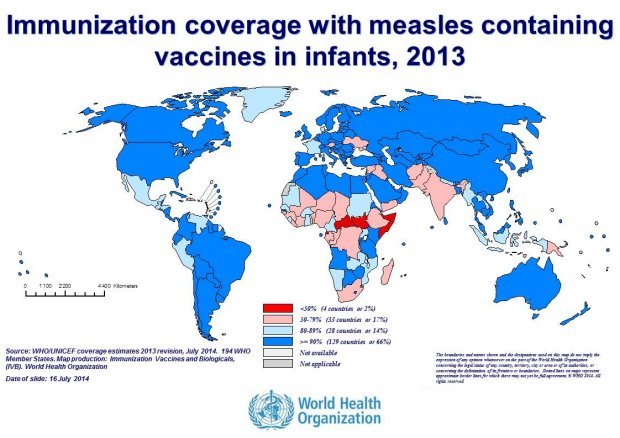

MEASLES RISK

By the end of 2013, just four countries in the world had less than 50 per cent immunisation among infants. With the rising cost, more and more countries could fall into this bracket, particularly in Africa and some parts of Asia.

DTP3 RISK

The diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP3) vaccine protects against three life-threatening diseases, and the map below shows how much coverage developing countries had achieved among infants by the end of 2013.

Only 30 per cent had immunised 80 per cent or more, and this percentage is likely to fall even lower as the cost continues to rise.