For Generation Insecurity, the British dream has turned sour

My 14 year old son is in a band.

He loves playing to his classmates and studying GCSE music. Bizarrely (for me), he’s quite into Queen and eighties songs, which I joke with him was the same stuff I was listening to when I was his age.

Intergenerational humour apart, it got me thinking about my son’s prospects when he leaves school, compared to mine in 1987 – and how, within the space of 30 years, the education, jobs and housing markets have changed, in many ways for the worse.

Like a lot of experts on the subject, I’ve concluded that my teenager’s cohort (“generation Z”) and the millennials a few years older than him face a much tougher climb when it comes to securing higher living standards than that attempted by previous generations.

For me – attending a state comprehensive – it was almost the norm to leave school at 16 with few formal qualifications. There was nothing like the cultural pressure to academically succeed that there is now.

I got just one O-level. It meant that I couldn’t go straight onto sixth-form, so I extended my Saturday job pushing trollies at Asda into a full-time role.

In those days, further education colleges ran extensive “night school” classes, which meant that you could retake the exams you failed at school while earning a living wage. Lots of adults – sometimes in their forties and fifties – would join these courses, which were free or heavily subsidised by local authorities. As the 1990s opened up, more working-class kids went off to university.

Of course, it is easy to look back at this period through rose-tinted glasses. Youth unemployment (16–18 year olds) was over 20 per cent in 1991. Access courses and higher education became a natural escape route for aspirational types like myself, with the government happy to offer university maintenance grants of £2,500 per annum, instead of handing out the dole.

By 2010, youth unemployment for 17 year olds hit 40 per cent, so the government, under Gordon Brown, took the step of abolishing the problem by extending the school leaving age to 18. That meant fewer unemployed teenagers, but also placed additional emphasis on attaining qualifications.

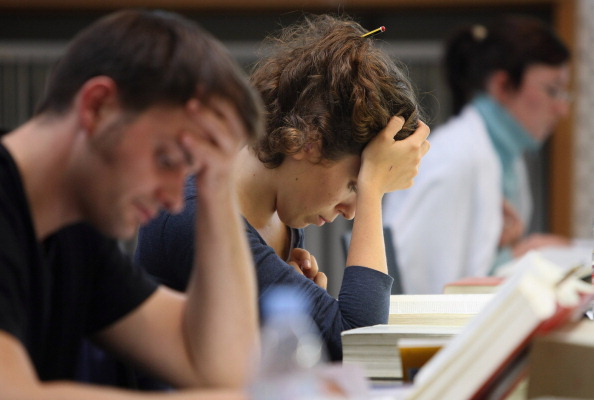

Over time, the pressure to succeed academically has become relentless. The so-called “British dream” is that if you can make it to university, a good job awaits.

For the 50 per cent of pupils that take A-levels in England, this pathway is well understood, at least at first. A-levels and their equivalents act as a direct entry route to degree courses. So far so good.

But what happens next? What awaits the other 50 per cent who don’t go to university – and, in fact, all young people, particularly graduates, once they hit their mid-twenties and are no longer studying?

The brutal fact is that my son’s generation, graduates or not, faces a new age of insecurity. The “British dream” has been mis-sold to them.

At a time when apprenticeships for young people have collapsed (despite the best intentions of the apprenticeship levy) and the further education routes open to me have been closed, those who do not excel academically have few options, while even those who follow the “right” path and earn a degree do not get the security they were promised.

High-pressure examinations have led to an epidemic of mental health issues in our schools and colleges. And instead of looking forward to more rewarding work and solid housing tenure, too many young people are facing the gig economy and the prospect of sofa-surfing. In the labour market, nearly 40 per cent of zero-hour contracts are taken up by 18–25 year olds.

For a select few – online influencers and celebrity YouTubers – the gig economy has bought untold riches. And insecurity is less of a worry for those with the Bank of Mum and Dad to fall back on. But for most young people, it has meant no sick pay, no holiday pay, and exploitation in the workplace.

Moreover, the unpredictability of work makes long-term financial planning and access to mortgages is virtually impossible.

In the late 1980s, it took a couple on average earnings around two years to save up for a home deposit; today it can take up to a decade, according to the Council of Mortgage Lenders. In London, a decade more.

For Generation Rent, whether graduates or not, the dream is turning sour. Indebtedness among under-30s has skyrocketed since the financial crash, homeownership has spiralled, and future earning prospects look bleak.

A recent study of graduate earnings has found that people like me, born in 1971, have been fortunate to earn twice as much from holding a degree, compared to those with similar degrees born after 1990.

Universities, meanwhile, continue to offer courses of dubious impact when it comes to providing students with the skills they need to succeed in the modern workplace.

With university courses now offered in “Heavy Metal Studies”, I’m left agog and slightly worried about just how my son’s musical, educational, and future job prospects might develop.

Tom Bewick is speaking at the session “From Zero Hours to Apprenticeships: young people at work” at the Battle of Ideas festival this weekend at the Barbican.

Main image credit: Getty