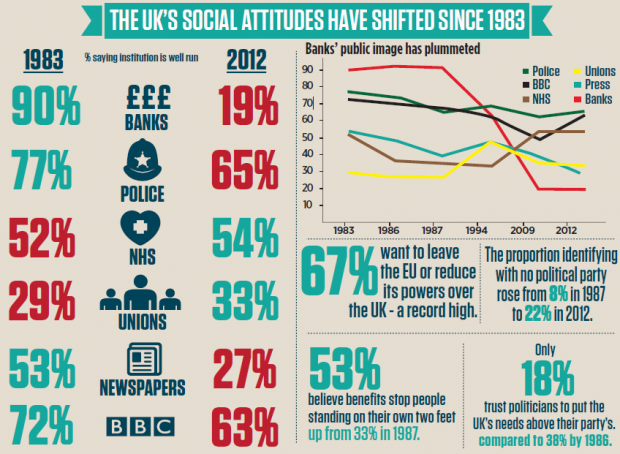

Banks were the best regarded UK institutions – now just 19 per cent believe they are well run

IN JUST 30 years British banks have fallen from being the UK’s most trusted institutions to some of the most loathed – and a devastating study out today shows their reputations are not improving despite the burgeoning economic recovery.

According to the landmark 30th annual British Social Attitudes report, released this morning, in the 1980s Britons thought banks were better run than the NHS, the police and the BBC.

But the sector shows no sign of repairing its reputation from the repossessions of the 1990s or the damage of the credit crunch, with distrust apparently deep and sustained – just 19 per cent think lenders are well run now.

The record low is down from a peak of 92 per cent in 1986, and represents a major blow to banks’ efforts to rebuild morale after the financial crisis.

“Public opinion, at least partly, reflects the behaviour of the people and institutions in question – whether they be politicians, journalists or bankers,” said the report, claiming that the solution is more hard work from financiers to show they can be trusted. “Their future public standing lies to a large extent within their own hands.”

Britain has also become markedly more eurosceptic over the last two decades. In 1991 just 11 per cent wanted to leave the European Union, while 31 per cent did in 2012.

The dedication of those who want to remain members or integrate further has also wavered – the proportion wanting a single European government has dived from nine per cent to three per cent.

“Living in a more globalised and diverse world has done nothing over the long term to persuade us of the merits of our membership of the European Union,” said the report.

“Euroscepticism is firmly in the ascendancy, with a record 67 per cent wanting either to leave or for Britain to remain but the EU to become less powerful.”

As dislike of the EU has grown so has a distrust of politicians domestically and a disengagement with party politics. The proportion of the public identifying with no particular party has grown from eight per cent in 1987 to 22 per cent in 2012.

The sense of detachment is particularly growing among younger voters. Only 66 per cent of those in their 20s and 30s felt engaged with any specific party last year, down from 86 per cent a generation earlier in 1983.

And the proportion trusting parties to put the UK’s interests above their own has plunged from 38 per cent in 1986 to 18 per cent in 2012.

But despite a lack of engagement with party politics, views on areas like welfare and public spending have shifted dramatically, implying a sustained interest in broader politics.

In 1991, 65 per cent of Britons wanted tax hikes to spend more on health education and welfare.

At the same time 33 per cent agreed that “if welfare benefits weren’t so generous people would learn to stand on their own two feet.”

By 2012 only 34 per cent wanted more taxes and more spending – just above half the level 20 years ago – and 53 per cent agreed welfare benefits undermine a sense of personal responsibility.

The report also found that – in a sign that public opinion does in some cases lead to policy changes – this strict attitude on handouts has resulted in spending cuts.

“The hardening in public attitudes towards welfare spending, although far from uniform, showed little sign of abating,” it said. “The coalition government has been emboldened by this popular mood to continue implementing its welfare reform agenda and even to heighten the political rhetoric accompanying it.”

However, there have also been a few signs the tough attitudes have been softening – the proportion believing the government is responsible for providing a decent standard of living for the unemployed stands at 59 per cent. That is below the 81 per cent in 1985, but up from 50 per cent in 2006.

- Osborne has defeated Ed Balls – but UK’s economy still fragile

- As the Social Attitudes Survey reveals softening views on welfare, is Britain moving to the Left?