How e-scooters, self-driving cars, and flying taxis will shape the future of your commute

An air of tranquility hangs about Stratford’s electric scooter riders.

Their bodies are still, poised, as they glide by on this crisp February morning. I try to copy them and end up skidding along, struggling to figure out how to position my feet — but after a couple of wobbles I’m gliding too. As I thumb the accelerator, the electric motor on my back wheel whines reassuringly. It feels faster than it looks.

We are in London’s Olympic Park. Somewhere around here, there are 50 electric scooters roving around as part of the first trial of its kind in the UK. Already widespread in other cities across the globe, they are one of several new modes of transport which could rewrite the rulebook on how people get to work in the coming years. The trial has been running for more than a year, but when I arrive there are only three available. They are clearly popular.

It is easy to see why commuters in the capital pine for something new. Drivers waste 227 hours each a year stuck in traffic, buses crawl through the centre at an average speed of 7mph, and getting on the Tube at peak times is stifling and claustrophobic. Meanwhile, the longest rail strike Britain has ever seen snarled up millions of Londoners’ journeys to work throughout December. There has got to be another way.

But help could be at hand. Tomorrow, the bosses of some of the most forward-thinking — and best-funded — mobility companies will gather in London at the Move 2020 conference. With electric scooters, self-driving cars and even flying taxis on the agenda, City A.M. takes a deep dive into three modes of transport which could revolutionise the way we get to work.

Micromobility: E-scooters

Electric scooters are illegal on Britain’s roads, pavements and cycle lanes. Anyone caught faces a £300 fine and six points on their driving licence — but you wouldn’t know it. On my half-hour cycle into the City I count five of them. One sails past a parked police car, whose occupants seem indifferent to the flagrant lawbreaking taking place at 15mph.

The truth of the matter is they are only banned by a 185-year-old law: the Highway Act of 1835. But that could soon change, with the government launching a consultation this month on how to regulate them — and improve safety in the process. London would join more than 100 other cities to facilitate the e-scooter trend, including Paris, New York and Tel Aviv.

Meanwhile, the companies popularising e-scooters across the globe are in their infancy. Bird, whose machines buzz around the Olympic Park by virtue of it being private land, and Lime, which already has an electric bicycle service operating in the capital, were both founded in 2017. They use a subscription business model whereby travellers can use an app on their smartphone to unlock the dockless scooters, which cost 25p a minute plus a £1 starter charge.

“We have to fundamentally revisit the way we look at the street. People look at the streets and see scooters everywhere. But they don’t see the 50 cars on the same road… Let’s challenge that assumption.”

Patrick Studener is vice president at Bird, and oversees the business across Europe, the Middle East and Africa. “There’s just so much traffic in cars that is really not needed,” he tells me, citing Transport for London (TfL) statistics that two thirds of city car journeys in the UK are less than three miles. About 60 per cent of those are solo trips. “Does it really take a one tonne steel vehicle to move a person individually for that distance?”

That thought process has certainly found favour in Paris, where Lime and Bird arrived in summer 2018. Now, more than 20,000 scooters — called “trottinettes” over there — swarm the French capital, and according to the Odoxa Institute, 11 per cent of Parisians have taken them for a spin. “If you could get that level of usage in London, it would be incredibly encouraging in terms of reducing vehicle journeys,” says Alan Clarke, Lime’s UK policy director.

Moreover, an internal Lime survey late last year suggested about one in four of the trips in Paris replaced a car journey. Given that pollution kills nearly as many people as smoking each year — and London is at the epicentre for dirty air in the UK — this can surely be no bad thing, Clarke says. “The benefits of that for air quality could be really significant.”

But Michael Hurwitz, director of transport innovation at TfL, is not yet convinced. “What we really would not want is that riding e-scooters discourages people from being physically active,” he says. “Sure, some people come out of cars, which is much better to be on their feet. But then some people are not walking anymore, which from a health point of view is less positive.”

And with new modes of transport come new perils. Paris saw its first trottinette death in June after a young man riding one was hit by a truck. Meanwhile, the UK was alerted to the dangers the following month, when 35-year-old Youtuber and TV presenter Emily Hartridge was killed in a collision with a lorry in Battersea.

Some Parisians have also been left embittered by the sheer clutter of tens of thousands of dockless scooters abandoned on the pavement. The pile-ups incensed the mayor of Paris’ 13th arrondissement, Jerome Courmet, so much that he enlisted a crack team to round them up. “Enough of this bullshit,” he menaces in a video posted in May, as workers load trottinettes onto a lorry behind him.

But Studener insists this is borne out of a skewed perception of how city roads should operate. “We have to fundamentally revisit the way we look at the street,” he says. “Those people look at the streets and see scooters everywhere. But they don’t see the 50 cars on the same road… Let’s challenge that assumption.”

So will these scooters flood London’s roads in the same way?

“That is one of my biggest worries, that the gates will just open,” says Hurwitz. When TfL replies to the government’s consultation, it will recommend a permitting system, he tells me. Then, the city can have a say in which companies operate and where the scooters are parked. “What I would really want to avoid is a situation where the market is opened, and then it is a free-for-all.”

Nonetheless, Lime and Bird know that people will hop on the scooters for one simple reason: enjoyment. “Anyone who has commuted in London on a long term bases knows how it is getting the Tube in peak hours,” says Clarke. “Lots of people would like an alternative to that.”

Studener adds: “I have a smile on my face every time I get off a Bird scooter. There is definitely something to be said for being outside and having the wind in your hair.”

And this is perhaps the most crucial point. By commercialising something genuinely fun as a means of public transport, companies like Lime and Bird are promising the commuters’ holy grail: a journey to work that people actually look forward to.

A mind of their own: Self-driving cars

When it comes to cars, the future is undoubtedly electric. Sales increased 144 per cent in 2019, and the government plans to ban selling new petrol and diesel cars in 15 years. But will humans still be at the wheel by then?

Predictions about the advent of the autonomous car have come thick and fast over the last decade. Some have been untested; others have been downright unroadworthy. Last year, Elon Musk, the outspoken chief executive of Tesla, proclaimed the electric car giant would release an army of 1m “robotaxis” onto America’s roads in 2020. He has since backtracked on this.

Volvo’s 2018 concept car, the 360c, goes a step further. It has no steering wheel, no driver, and the front seats face backwards. It is more of an autonomous transport pod than a car as we know it. Industry experts are sceptical that it could become a reality anytime soon.

“I’m not sure we’re going to see it in the next five or 10 years,” says Jamie Hamilton, of Deloitte’s automotive team. “People will need some convincing that it’s safe to get in a car with no steering wheel, and also that it’s safe to be on the road with them.”

Disquiet has been brewing since March 2018, when a self-driving car designed by Volvo and Uber struck a woman at 44mph, killing her as she tried to walk a bicycle across the road in Arizona. The resulting court case found the car’s safety operator was to blame; she was watching an episode of reality show The Voice while sitting behind the wheel. But it also found that the self-driving system spotted the pedestrian five seconds before hitting her, and could have slammed on the brakes. It just failed to identify her as a human.

If you could have two vehicles a metre apart travelling at the same speed, you’re going to get a damn sight more traffic going through the city.

Nevertheless, Hamilton is sanguine about the technology’s chances of entering the mainstream one day. “Don’t get me wrong, it is a matter of when,” he says. “Whether that’s mass ownership, or if it’s more of a niche like autonomous taxis, it’s less clear.”

Oxbotica is leading the charge in the UK on developing the software, and last year tested a fleet of driverless Ford Mondeos on public roads, also around the Olympic Park in Stratford. Its founder, Paul Newman, tells me: “We’re already getting close to a place where you could say we could run a small shuttle service in a city — something like the ultimate bus. That is within reach. But it’s a long time before you can walk into a dealership and say: ‘I’ll have a car without the windscreen and no steering wheel,’ and it’ll have the same functionality as a car does now.”

However, when that day comes, the effect on our lives could be “profound,” Hamilton says. “The commercial opportunities are quite significant. Passengers could work, they could be entertained — and the autonomous car will know where they are too, so you could even have location-specific offers.”

If commuters look outside, they may see narrower roads, as cars yield long-undisputed territory to cyclists and pedestrians. That is because of the superhuman precision of self-driving software, adds Michael Woodward, also from Deloitte. “If you could have two vehicles a metre apart travelling at the same speed, you’re going to get a damn sight more traffic going through the city. Commute times will actually come down.”

All the same, even this space-age utopia is not without its flaws, according to TfL’s Hurwitz. He is concerned that, like electric scooters, self-driving cars could stop people using more active modes of transport, like walking or cycling. “That is not going to be great for our ambitions to have a healthy city,” he says.

Moreover, he frets that they could abet congestion just as easily as relieve it. “It could be heaven or hell. The worst-case scenario is someone going to the theatre, for example, and just pressing the button on their autonomous vehicle and getting it to drive around until they come back because it’s cheaper than parking.”

For now, however, autonomous tech tends towards making normal cars safer, and it is more commonplace than some might think. 1,000 London buses already use self-driving technology that regulates their speed. Emergency braking, lane-changing and self-parking are permeating the new car market. The latest Teslas will even crawl out of the garage on their owners’ command.

“Some of the building blocks are already there,” Hurwitz says. “But what we are going to see is evolution, not revolution.”

Pie in the sky? Flying taxis

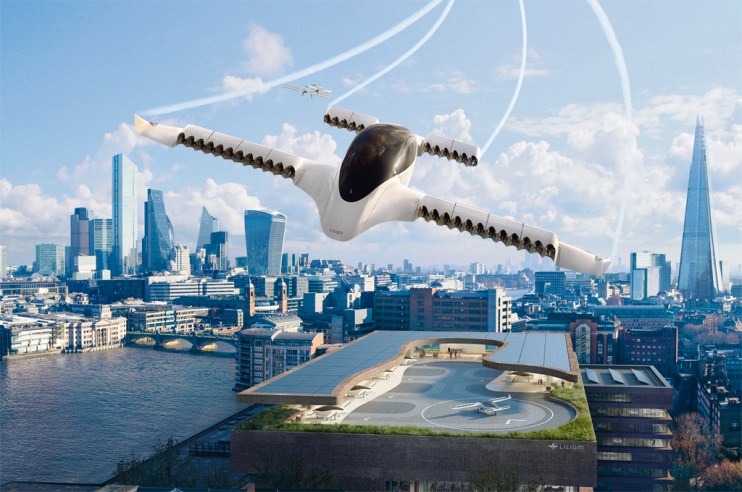

If self-driving cars are a long way off, one could be forgiven for thinking that air taxis are a flight of fancy. But dozens of startups are betting the so-called urban air mobility market is getting ready for take off. With futuristic names like Volocoptor, Eviation and Lilium, they are already jostling for a first-mover advantage. Some hope to launch a service in the next five years. London could be one of their first destinations.

Last year, Lilium, a German company founded in 2015, celebrated the maiden flight of its sleek five-seater prototype jet. The aircraft, which is known to those in the industry as an eVTOL (electric vertical take-off and landing vehicle), has 36 engines spread across four rotating wings. It can hit 186mph. Remo Gerber, the company’s chief commercial officer, tells me he hopes it will have a taxi service “operational and relevant in several locations around the world” by 2025.

He is quick, however, to dismiss the idea that people could use Lilium for short hops within the city, like a conventional taxi ride. “It is a proper aircraft, a serious tool — it’s not going to land in your garden,” he says. Instead, Gerber envisages a situation where travellers can book a trip from London to Brighton the night before — “or an hour before” — via an app. “You go and show up at the pad at Embankment [for example], and then you fly to Brighton in about 15 minutes.”

Perhaps, then, it is more appropriate for people coming in from commuter belt towns, many of whom currently rely on a rail network which has been blighted by strikes in recent months? “Absolutely,” he says, adding that a ride with Lilium would cost roughly the same as a rail fare. “But the big advantage that we have over trains is that you don’t need to maintain the tracks in between. In the long run, you’re looking at multiples less in infrastructure costs.”

The technology is there. From a technical point of view it is absolutely possible.

But is it a bluff to attract more investment, or are Lilium’s ambitions realistic? For the long term, at least, analysts think the latter. Research drones are already flying in 64 cities around the world, and Morgan Stanley has predicted that the urban air mobility market will be worth $1.5 trillion a year by 2040. It thinks passenger traffic will account for more than half of that.

And it’s not just startups. The biggest names in aviation are also working on eVTOLs. Plane makers Boeing and Airbus, as well as jet engine manufacturer Rolls-Royce are among them. Even Uber has joined the race.

Warren East, the chief executive of Rolls-Royce and an engineer by trade, takes a measured stance. “The technology is there,” he tells me. “From a technical point of view it is absolutely possible.” However, getting a business model like Lilium’s past the UK’s airspace regulator, the Civil Aviation Authority, may pose a challenge, he adds. “Our piece in the jigsaw puzzle is only part of it. There’s a huge amount of regulation and air traffic control that would also need to be in place.”

London already has the most complex, congested airspace in the UK, adds TfL’s Michael Hurwitz, who tells me he has spoken with a number of the startups. “Normally the evolution of technology is such that you do not come and try things in the toughest areas. But what we said is ‘look, if you want to start anywhere, it has to be the uses that have a social benefit.’”

“Because of the cost, a lot of these technologies will start as premium services,” he says. “That’s all well and good, but I prefer it when a new mode of transport is available to everybody. I like it less when it is only available to the affluent and the tech-enabled.”

Lilium is undeterred. Last year, it picked London as a base for hundreds of software engineers. Meanwhile, Parisian authorities have already agreed to let Airbus bring a flying shuttle service to the French capital for the 2024 Olympic Games. Uber has a similar arrangement with governors in Melbourne. Dubai first tested a drone taxi service three years ago.

Flying taxis or not, more than two thirds of the world’s population will live in cities like London by 2050. Rush hour is only going to get worse. The Royal Society for Public Health has even said the stress involved with getting to work is shortening people’s lives. Commuters are increasingly snacking, failing to find time to do any exercise, and struggling to get enough hours of sleep.

It is problems like these that exhibitors at the Move 2020 conference are trying to overcome. Along with e-scooters and self-driving cars, taking to the skies could form part of the solution.

Move 2020 runs from 11-12 February at Excel London.