Brexit delivered £1,000 blow to every UK household, Bank of England rate setter Haskel claims

The sharp reduction in business investment after Brexit has dealt a £1,000 blow to every UK household, a rate setter at the Bank of England has claimed.

Speaking to The Overshoot, Jonathan Haskel, an external member of the monetary policy committee (MPC), said that the “productivity penalty” caused by a huge drop in capital spending since the 2016 referendum has amounted to 1.3 per cent of lost GDP growth.

If investment had continued on its pre Brexit trend, the economy would have been around £29bn larger, Haskel said.

A big slowdown in intangible investment – things like intellectual property and boosting employees’ skills – has led overall capital spending lower in the UK since the financial crisis, dragging productivity growth down with it.

“Since the financial crisis, there has been a slowdown in the pace of intangible investment—not so much in the US, but a bit in Europe and a bit in the UK And so that means with less intangible investment going on, that slows productivity,” the rate setter said.

Most rich economies have experienced a slowdown in productivity growth since the banking crisis in 2008, but Britain’s decline has been much deeper, mainly because the country has a larger financial sector, Haskel said.

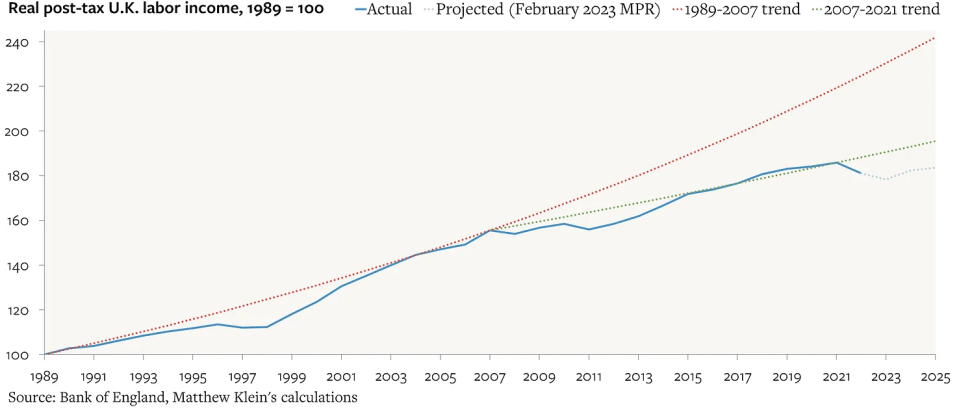

UK living standards growth has stalled since Brexit

“But I think it really goes back to Brexit. If you look in the period up to 2016, it’s true that we had a bigger slowdown in productivity up to 2016, but we had a lot of investment. We had a big boom between 2012-ish to 2016. But then investment just plateaued from 2016, and we dropped to the bottom of G7 countries,” he added.

Rising productivity growth is key to boosting household living standards as it enables businesses to hand workers pay rises without strengthening inflation.

Brits have been heavily exposed to the current cost of living crisis due to weak productivity growth for more than a decade keeping a lid on pay growth.

Haskel, who voted with the 7-2 majority at the Bank’s last meeting earlier this month to raise interest rates 50 basis points to four per cent, said the UK is “caught in this terrible bind of having a U.S.-style tight labor market with a European-style tight energy market”.

Inflation last year raced to a 41 year high of 11.1 per cent in October, but has since dropped two months in a row to 10.5 per cent.

The Bank reckons inflation is on track to decline to around four per cent by the end of the year, still double its two per cent target. It has raised rates 10 times in a row.