The big independence lie: Why Scotland could keep the pound

Truth is usually the first casualty of political battles, as it is of war. I believe that Scotland and England are individually stronger for being part of the UK, but 25 years in currency markets tell me that the No campaign’s argument that Scotland cannot keep the pound is false.

It would certainly be a limited version of independence, but there is nothing stopping an independent Scotland from declaring sterling sole legal tender and borrowing it on the financial markets to hold in reserve. However much it may appear to be like having your cake and eating it, neither action requires the permission of the rest of the UK.

First, the list of countries that have adopted a currency issued by another state, outside formal agreement, officially or not, includes past monetary sinners like Russia in the 1920s, Mexico in the 1980s and many others. Today, it also includes about 30 small countries from Andorra to Panama and the Vatican that have officially chosen to do so. History and the present day teach us that currency substitution is possible. It should also be easier for Scotland than others, because it already uses sterling and its economy is tightly integrated into the rest of the UK economy.

Second, the Bank of England cannot even deny sterling liquidity to any Scottish-focused bank prepared to put up the necessary collateral, without jeopardising sterling’s international liquidity and external value. Moreover, assuming Scotland continues to run a healthy external balance of payments, courtesy of 90 per cent of the UK’s oil and gas being in Scottish waters and other foreign currency earners like whisky and tourism, sterling liquidity will likely flow from the rest of the UK to Scotland. Scotland will be a net lender to England.

LATEST ON SCOTTISH INDEPENDENCE

Scottish independence currency contingency plans in place, says BoE's Mark Carney

Scottish independence: Danny Alexander will continue to oppose currency union in case of yes vote

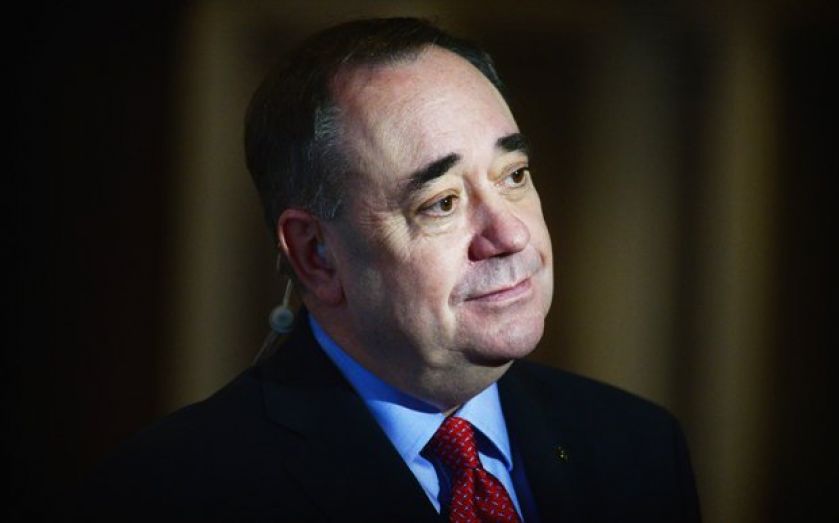

Alex Salmond: "There is literally nothing anyone can do" to stop independent Scotland keeping the pound

Third, it is easier to fight the last war, so the argument has followed that, if the collapse of the bank funding markets in 2008 were repeated, the Bank of England would not be a lender of last resort to the Scottish part of banks. This would be difficult, but not impossible given that loans require capital, and the Bank could insist that this capital is ring-fenced between the two economies.

But fourth, while many rightly note that an independent Scotland using sterling could not print currency and devalue, the benefits of being able to do so are themselves not free. Beyond those that have adopted another state’s currency, there are a further 20 relatively successful countries – like Hong Kong, Denmark and Saudi Arabia – that have chosen a rigid exchange rate fix with another currency without seeking permission. They are also unable to provide unlimited liquidity to their banks without devaluing – something most have avoided for decades.

They have made the decision, however, that the long-term costs of governments giving in to pressure to inflate (or financial markets second-guessing whether they will) outweigh the short-term benefits of flexibility. Instead, they have chosen an exchange rate fix as a signal of fiscal and regulatory responsibility. They tend to be small countries, where the benefits of exchange rate devaluations are scant anyway, because there are few competitive local alternatives to most imports, and their main exports, like oil and gas, are priced in US dollars.

Fifth, many also question the cost-benefit of a public sector bail out of banks. The UK and other G20 governments have spent much energy on how to avoid bailouts next time. Initiatives include new bank winding-up arrangements under the proposed European banking union, requirements for banks to self-insure themselves through instruments that convert to equity or cash when a bank is in trouble, and new liquidity coverage requirements for banks. If it kept sterling, the Scottish side of any fence would need to rely more heavily on these mechanisms. But it could still be done.

One of the few compensations of watching politicians make false debates out of serious issues is the irony of seeing Alex Salmond champion sterling and George Osborne purvey the merit of bailing out banks. Perhaps the heat and fury is about positioning ahead of separation negotiations. But this would seem to be a defeatist tactic that could backfire.

If the English position is that the Bank of England is not an asset to be shared, an independent Scotland, like other newly-independent states before, will feel it can legitimately disown any share of past debts. Further, pretending that England has nothing to lose, and Scotland much, is one falsehood that helps to distract from the other – that independence is mainly about dividing up North Sea oil and gas.

Independence is about taking responsibility. Without fiscal, regulatory and institutional responsibility, an independent Scotland will not succeed, whatever its currency arrangements, and as ordinary Venezuelans, Nigerians and Russians can attest, even with all the oil and gas in the world.

Avinash Persaud is emeritus professor of Gresham College, chairman of Intelligence Capital, and a former global head of currency research at JP Morgan.