Argentina looks to restructure debt as default looms

Argentina is looking to escape another sovereign debt default by placing its restructured debt under local law instead of US law, to bypass the US supreme court decision that saw the Latin American country facing the repayment of $15bn in debt in one chunk.

The supreme court ruled for the hedge funds Argentina has been battling for the last decade, after they refused to take part in a debt restructuring process following the country's default in 2001. If no solution is found by 30 June then US courts will block Argentina from making payments on its debt, resulting in a default.

Reuters reported the Argentine economy minister, Axel Kicillof, as saying:

We cannot allow (holdouts) to prevent us from honouring our commitments to creditors. For this reason we are starting the steps to start a debt swap to pay them in Argentina under Argentine law.

The problem with this, according to Joseph Cotterill at the FT, is that moving bonds away from the jurisdiction of the US courts isn't terribly clever, given that the courts are unhappy with Argentina anyway and further antagonism reduces the chance of postponing the injunction.

This is an issue, says Cotterill, because the Argentines intend to continue negotiating with the court order's author, Judge Griesa while they try to move the bonds out of his reach.

As Business Insider reports, Argentina's populist president Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner gave a long, public speech on the subject this week, in which she said Argentina was "willing to negotiate, but not willing to be extorted by the international markets." She called those who had invested in Argentine bonds when they were at junk status as "vultures."

The problem for Kirchner is that when it comes to economics she has somewhat alienated the international community with the hostile takeover of Spanish oil company Repsol, with whom a compensation deal was reached in February.

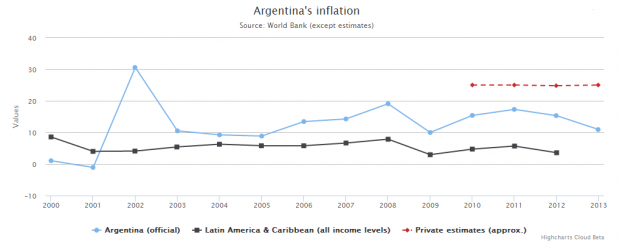

What is more, the Argentine economy is not in fine fettle, GDP growth slowed to 1.4 per cent at the end of 2013 and the inflation rate is probably dangerously high at 25 per cent, far higher than official figures suggest. Even the official rate of around 11 per cent is far higher than the regional average. Argentines with longer memories will recall the misery of hyperinflation well – levels topped 3000 percent in 1989.

The results of this latest tussle will be keenly watched as an Argentine default would have a big effect on the regional economy. The effects of the 1998 – 2002 great depression and the 2001 default are not forgotten either.