Why Labour will need to fix the UK’s labour market to unlock economic growth

Both parties have pledged to put growth at the core of their economic agenda if they win the general election, a welcome recognition of the UK’s dismal performance since the financial crisis.

So far, however, its unclear exactly how either Labour or the Conservatives will generate the kind of economic revival they are promising to deliver.

One thing is for certain though: they’ll need to address the major challenges holding back the UK’s labour market, and do it fast.

Why does the labour market matter

Its easy to see why an economy’s labour market is important for boosting economic growth, and indeed a growing labour market has been one of the major drivers of growth over the past few decades.

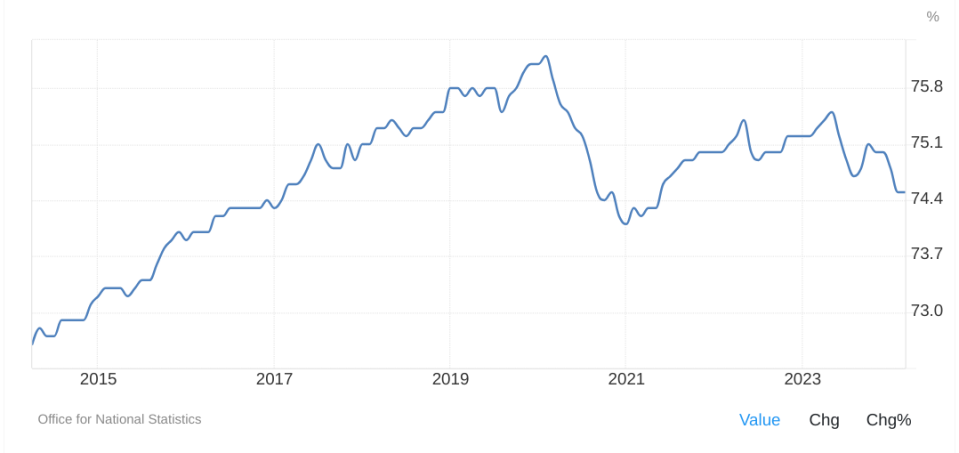

Between 1994 and 2019 the annual labour force grew by around 250,000 people, partly as a result of high levels of immigration and partly due to higher domestic participation. Consistently increasing levels of employment was one of the (few) major economic achievements of the 2010s.

“It has been this continual growth, through recession and recovery, that has helped to pull up economic growth even as productivity has stagnated,” Tony Wilson, director of the Institute of Employment Studies, said.

However, this trend has gone into reverse since the pandemic. Wilson argues that now the labour market is in a situation where it risks holding back growth for the first time since the 1990s.

What’s the problem

The main problem facing the UK’s labour market is increasing levels of long-term sickness. 2.7m people are out of work due to ill-health, up from 2.1m people pre-pandemic.

An increasingly sick population means the UK is the only G7 economy where employment has not recovered to its pre-pandemic level.

This is not just about an older population. Raoul Ruparel, director of BCG’s Centre for Growth, said the increase in long-term sickness was “most notable for young people, often with multiple mental health conditions, and for older workers with physical ailments.”

Not only does a smaller workforce mean the UK’s potential output is lower, increasing inflationary pressures, but a sicker population puts a greater fiscal burden on the government. Getting people back into work is therefore doubly good: it boosts growth and improves the government’s fiscal position.

While there is a shortage of labour on the whole, certain sectors – construction, tech and social care in particular – have suffered acutely from a dearth of skilled workers.

The government’s most workplace survey found that nearly a quarter (23 per cent) of workplaces had at least one vacancy, while one in ten reported a vacancy due to a skills shortage. A recent parliamentary report, for example, found that the UK did not have enough skilled workers to develop its major infrastructure projects

“There is a real risk of a skills shortage affecting growth,” Ruparel said. “We have a population-wide lack of digital skills and more sector-specific challenges in engineering, construction and social care which could have wider knock-on effects for the UK economy.”

What to do

Neil Carberry, chief executive of the Recruitment and Employment Confederation, said any response to these issues needed to start from the premise that “all labour supply is local”.

His point is there will be big regional variations in how these national issues unfold, and policy needs to reflect that.”Its not diktat from Westminster, the action is on the ground,” he told City A.M.

In its own manifesto, the REC said the government needed to relaunch the Workplace Employment Relations Survey, which last ran a decade ago. This survey would provide evidence on how the labour market is really working, helping co-ordinate between businesses, educational institutions and jobcentres.

Wilson has argued that jobcentres need to be more focus getting people back into work rather than checking people are meeting the conditions for benefits. OECD analysis shows that a smaller proportion of unemployed people in the UK use the public employment service than in any other European country.

Another core part of the debate on the workforce has been around reform of the apprenticeship levy. Businesses pay the levy into a fund which can then be accessed to help fund apprenticeships.

The only problem is it does not seem to be working. Since the apprenticeship levy came into force in 2017, the number of young people starting on the programmes has dropped by 41 per cent for under 19s and 36 per cent for those aged 19 to 24.

What have the parties said

Both parties have made a splash around getting people back into work. Over the past three fiscal events, the government has made its back-to-work plan a core part of its economic pitch.

The Conservative approach is classic carrot and stick: try and provide better support for those out of work due to sickness while making it more difficult to receive welfare for those deemed unworthy.

Last Autumn, it announced plans to expand four major programmes offering support to people with mental health conditions. On the other hand, they have also pledged a major overhaul of the welfare system which would potentially prevent people with minor mental health issues receiving the main disability benefit.

Rishi Sunak has also pledged to scrap what he called “rip-off degrees” in favour of creating 100,000 more apprenticeships per year.

Labour’s own workforce plan intends to lift the employment rate from 75 per cent to 80 per cent, equivalent to over 2m extra workers.

This would be achieved through the creation of a new national jobs and careers service, bringing together local jobcentres and the careers service. Liz Kendall, the shadow Work and Pensions Secretary, said Labour would also bring in “new local plans” to get people with health conditions back into work.