The Debate: Would citizens’ assemblies improve our democracy?

City A.M.’s weekly feature takes the fiercest water-cooler debates and pits two candidates head to head before delivering The Judge’s ultimate verdict.

This week: Should the UK introduce citizens’ assemblies?

Yes: In Ireland, citizens’ assemblies helped identify a new consensus point for abortion rights

The 24-hour-long ‘moment’ we just experienced around citizens’ assemblies has been very revealing.

Criticisms have included the idea that these assemblies are too slow, too expensive, too likely to be unrepresentative of the wider public, or even tantamount to the abnegation of responsibility by our elected representatives in parliament.

My response to each of these – as someone who has been involved in some of these experiments, studied them as an academic, and done some policy thinking about them in my time in think tanks – is that any of these issues is possible… in a badly designed assembly. But politicians do not “own” or “generate” political discourse, or policy decisionmaking – any more than hospitals “own” or “generate” health.

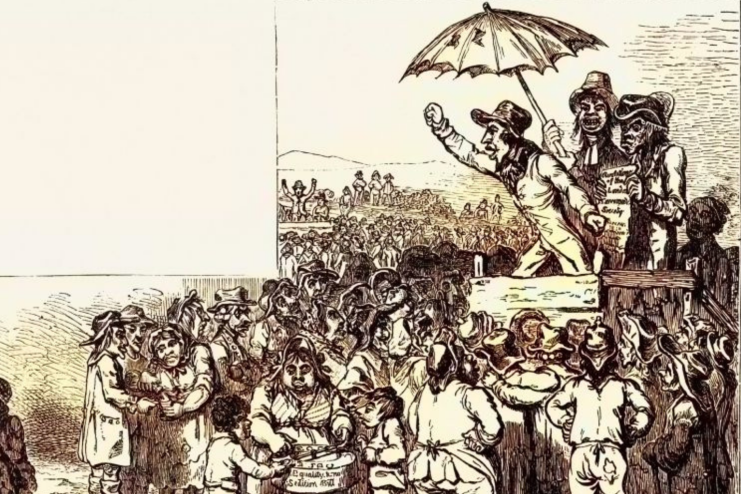

Citizens’ assemblies, juries, panels and other kinds of participatory and deliberative forums have been growing in use around the UK for years now. At worst, they can be a kind of elaborated, extended focus-group – useful mainly as an indicator, albeit of dubious reliability, of public opinion around some issue.

However, when done well, these deliberations can have a transformative impact. In Ireland, they helped identify a new consensus point for abortion rights. Brazil has pioneered a participatory budgeting approach that builds ownership and understanding of financial trade-offs and allows investment to reflect the priorities of citizens.

Goodness knows we face a plethora of issues which have not, so far, been particularly amenable to traditional electoral politics.

The remit of citizens’ assemblies must be tightly defined – ideally, in terms of connection to a particular place, where participants have ‘skin in the game’, as well as a clearly singled-out issue. Enormous efforts must be made to achieve a representative and cognitively diverse group of participants. And care must be taken that the informational component is not in any way biased or one-sided: stick to the facts, and balance your experts from across the spectrum of opinion.

Then, maybe we can deliberate our way to better decisions.

No: We shouldn’t pretend citizens’ assemblies are democratic when they’re the opposite

Citizens’ assemblies have long been a policy in search of a problem. First popularised in Ireland, they have been proposed to solve Brexit, the climate and migrant crisis and even democracy itself.

They were first proposed by political scientist Robert Dahl, who worried that voters weren’t studying issues in depth and suggested the creation of a ‘minipublic’, to encourage engagement and overcome ‘rational ignorance.’ So far, so noble – but in practice citizens’ assemblies are a way to manage democracy, rather than improve it.

Each assembly discusses a predetermined topic. But in real life, issues are interlinked, and limiting discussion to a single topic means the process of debate must be managed. This is not only undemocratic, but limits the range of policy responses the assembly can offer.

These debates are also guided by ‘experts.’ But who defines ‘expert’, and who is responsible for this decision? The selector will, of course, be carefully appointed by government through a plausibly deniable arm’s-length body, ensuring a stream of undoubtedly lucrative jobs for ideological allies.

We already have means of engaging the body politic on specific issues. Allow me to introduce you to the concept of referenda, which solve all the problems that citizens’ assemblies seek to handle. Worse still, citizens’ assemblies allow politicians to depoliticise their decisions by outsourcing decisionmaking to a supposedly apolitical forum that can in fact be subtly but easily rigged.

We shouldn’t pretend that citizens assemblies are anything other than a forum to give a veneer of legitimacy to decisions already taken. And we certainly shouldn’t pretend they’re democratic.

Verdict: The City could be a better place thanks to some localised democracy

This week it emerged, via a certain Sue Gray, that Labour had plans to introduce citizens’ assemblies to guide policy on divisive issues such as constitutional reform, devolution and housing. However, the party bashed that idea down in less than 30 hours.

So clearly, bringing together a randomly selected group of citizens to debate a particular issue remains contentious. Jones slams the idea as essentially undemocratic, due to the selection process and its necessary supervision. Yet few people object to juries, which are chosen in a similar manner.

It’s true that an authority must predetermine the subject (as it would in a referendum), but that doesn’t mean the conclusion is preordained.

The most successful have been in Ireland, as Kaye mentions, taking the temperature on abortion, giving the government and the country the confidence to move forward with moral certainty.

But the Climate Assemblies in the UK were also highly successful despite offering more complex solutions, identifying eight preferred policy areas through which to reach net zero – despite Jones’s assertion that assemblies are ill equipped to deliver complex outcomes.

At City A.M., we are hard pressed to fault the idea of citizens’ assemblies. The prestigious and well-informed residents of the City of London, armed with knowledge gained from reading this esteemed newspaper, would be excellently placed to make decisions on housing (build more), the tourist tax (abolish it) and public squares (create as many as possible).