Space, the investment frontier: The companies that are reaching for the stars

When Neil Armstrong was the first man to walk on the moon 50 years ago, space was the exclusive domain of two superpowers.

Now it has become perhaps the ultimate competitive arena for two tech giants — not to mention a host of other private enterprises that see untold promise and profits in reaching for the stars.

On 4 October 1957, the USSR launched Sputnik I, the first-ever artificial satellite. It marked a major step forward in Soviet efforts to develop an orbiting nuclear-strike capability and was the first telling blow of the original “space race”.

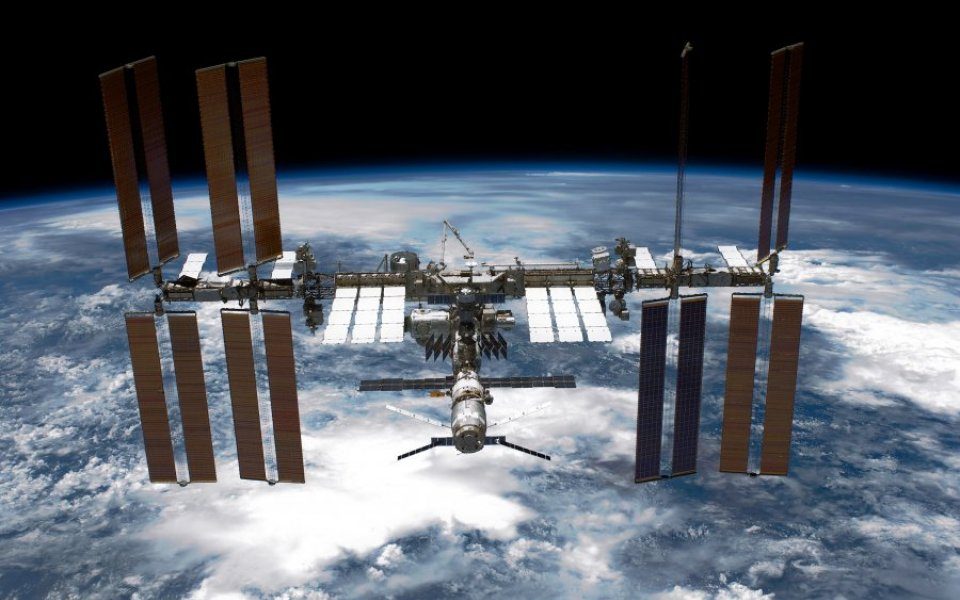

Today, as the conquest of space enters a radically different era, the Cold War is long forgotten. The US and Russia have joined a dozen other nations in a quest to “expand human presence into the solar system”, and the United Nations has opened an Office for Outer Space Affairs.

Yet by far the most significant shift is that companies, not countries, are now leading the way.

Two in particular are at the forefront: Blue Origin, established in 2000 by Amazon founder and chief executive Jeff Bezos; and SpaceX, established in 2002 by Tesla founder and chief executive Elon Musk. Space is no longer the exclusive preserve of a select few government agencies: it is the stellar playground of tech billionaires.

Blue Origin made history by completing the first-ever landing of a reusable rocket. SpaceX launched the most powerful working rocket ever constructed. Both have rapidly cemented their positions as go-to contractors for Nasa and other space agencies, as well as for telecommunications companies that continue to add to the thousands of man-made satellites circling the Earth.

Reusable rockets operate at a fraction of the cost of their government-funded counterparts, and have quickly come to constitute a reliable business model. This has allowed Bezos and Musk to muscle in on territory that was for decades dominated by long-standing Nasa suppliers, such as aerospace giants Boeing and Lockheed Martin.

Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic is pursuing similar objectives. So, too, are the numerous startups that are increasingly entering the burgeoning market for commercial space travel.

As has been witnessed in other technology-driven sectors, the pie is likely to be divided into ever-thinner pieces – and some of the smallest and most nimble competitors could prove to be among the genuine game-changers.

The emergence of a robust and even crowded marketplace, particularly one in which entrepreneurship is a key dynamic, raises a number of difficult questions. Is space the next investment frontier? Who controls space? Who owns space? As leading British space scientist Professor Monica Grady has observed: “Once investment starts to flow, lawyers won’t be far behind.”

The Outer Space Treaty, which is overseen by the UN’s Office for Outer Space Affairs, is a framework with text formulated for nation states, rather than for private enterprises. It asserts, for example, that no country can lay claim to any celestial body.

Yet companies are already assessing the feasibility of “space mining” and extracting water from the Moon and other natural satellites, not least because it has been estimated that using hydrogen as rocket fuel could reduce the cost of spaceflight by up to 95 per cent.

Moreover, as private companies look to increase profits by cutting costs, greater risks will be taken, in all likelihood, at the expense of human safety requirements. Professor Grady continues: “As the field develops and additional private companies move into space exploration, there will be a higher probability of accident or emergency.”

Bezos, via Blue Origin’s website, clearly states we are not in a race: “it is an illusion that skipping steps gets us there faster”. Does he mean it? The truth, as with so much else in this new era of space exploration, is very much up in the air.