Real emerging market risk is not repeat of 1997 Asian crisis

Don’t prepare for a reversal in market’s appetite for risk anytime soon

TO SOME analysts, the bloodbath in emerging markets over the past fortnight bears uneasy similarities to the early stages of previous full-blown emerging market crises. As a recent note by Brewin Dolphin pointed out, such episodes have historically recurred every 15 years or so. Given the date of the last one (the Asian crisis which started in 1997), we could be overdue.

January was a torrid month for emerging markets, of course. What started as an isolated sell-off in a few vulnerable currencies rapidly escalated into broadbased chaos. Dollar-Turkish lira collapsed from TRY2.17 to 2.34 in the middle of the month – it stood just below TRY2.29 yesterday. Brazil’s real has lost nearly 2.2 per cent of its value since the start of January, and dollar-rand yesterday stood at ZAR11.25, the South African currency worth 6.7 per cent less than at the start of the year. The Argentinian peso fell by 23 per cent.

And panic has set in, impacting equities across the world. The MSCI Emerging Markets index began January above 1,002, before falling 6.6 per cent to less than 937 by Friday. The release of disappointing Chinese data yesterday saw the index weaken by a further 0.4 per cent. And risk aversion has extended to the developed world, raising concerns of contagion. In January, the Dow Jones tumbled 5.3 per cent, and the S&P 500 slid by 3.6 per cent – their worst monthly percentage declines since May 2012. Yesterday, the S&P hit its lowest level since October, albeit influenced by poor US manufacturing data.

But will market chaos lead to another fully-fledged crisis, or should traders be on the look-out for signs of a reversal of the panic? Is this time different?

THE SAFETY VALVE

“Things are indeed different,” says Saxo Capital Markets chief executive Torben Kaaber. “The fact that the Fed was willing to continue its tapering programme despite the turmoil in emerging markets is telling – the threat of contagion, while real, is not as elevated as it may be perceived.” And while former darlings like India and Brazil are currently suffering from their failure to make significant structural economic reforms, changes to currencies since 1997 have arguably made them less vulnerable.

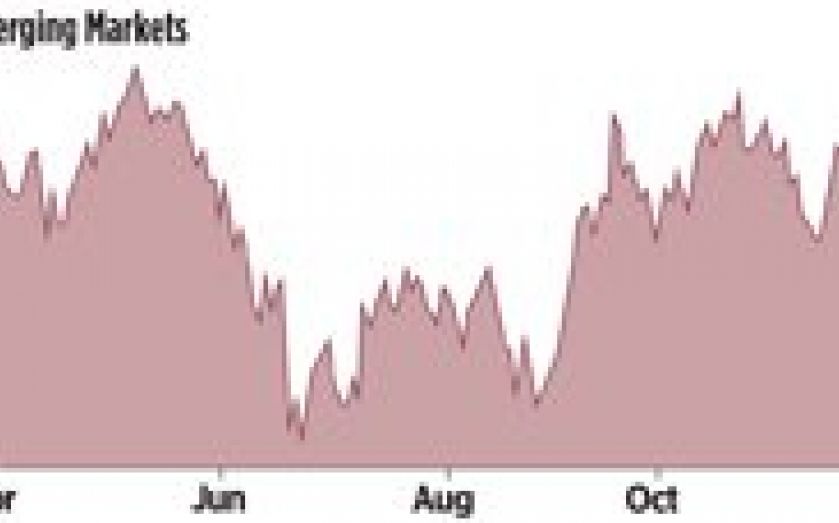

First, most emerging economies now have flexible exchange rates, as opposed to the currency pegs widely seen in the late 1990s. As Emily Whiting of JP Morgan says, a floating rate “acts as a pressure valve” – part of the necessary adjustment can be born by the currency, also helping to improve the current account deficit. In a recent note, Rabobank’s Christian Lawrence pointed out that most emerging market currencies have already seen a fairly broad-based adjustment (see chart). While there could still be room left to run, the fact that these corrections are allowed at all is widely seen as healthy.

Despite this, many worry that monetary tightening (particularly Turkey’s decision to hike its key one-week repurchase rate from 4.5 to 10 per cent last week) could halt further adjustments and spark an escalation of the crisis. Writing in City A.M. last week, Danske Bank’s Lars Christensen argued that Turkey’s attempt “to prop up the lira by aggressively tightening monetary conditions is effectively an attempt to quasi-fix the exchange rate.” If Christensen is correct, Turkey could be making the same mistakes as Thailand in 1997, when its attempts to maintain the baht’s peg against the dollar merely postponed the inevitable, eventually resulting in a complete collapse and recession.

More broadly, even though Turkey has been exceptional in its policy measures (South Africa and India raised interest rates by just 0.5 and 0.25 per cent respectively last week), tightening is certain to harm growth. Even before the central banks acted, the IMF had already slashed emerging market growth forecasts – notably cutting its outlook on 2014 Russian growth by 1 per cent, despite rising confidence in the global economy.

FX RESERVES

Ashraf Laidi of City Index says that the volume of foreign exchange reserves held by many emerging market central banks may help prevent an all-out crisis. “Higher reserves provide nations with a better cushion to stave off attacks against their currencies.” By selling their reserves to buy domestic currency, central banks can help to minimise the sharpest swings. Between 2000 and 2008, it is estimated that emerging market foreign exchange reserves grew from less than $1 trillion to $4.7 trillion, and India announced that its reserves stood at $292bn as of 24 January this year. But Lawrence questions how effective the strategy could be in the face of stronger market moves – “we have certainly seen the ineffectiveness of intervention in Turkey, where attempts to halt the pace of lira depreciation through sales of foreign reserves proved literally to be a waste of money.”

MORE DIFFERENTIATION

If the odds of a full-blown emerging market economic crisis are longer than in the 1990s, does this mean traders should prepare for a sharp reversal in risk sentiment? Not according to Michael Hewson of CMC Markets. “Risk appetite is likely to have a more defensive bias in the future as higher interest rates in emerging markets limit growth prospects.”

In emerging markets, Lawrence expects increased differentiation between economies as panic fades. Comparisons to the Asian crisis of the 1990s “led to non-specialist investors dumping any exposure they have to emerging markets, regardless of the underlying story of the specific currency.” If and when the crisis mindset reverses, however, currencies with better fundamentals (like the Mexican peso and Polish zloty) will likely benefit, he says. Such currencies seem to have mainly been tarred by association, despite their relatively promising fundamentals.