Art review: Agnes Martin brings peace and quiet to Tate Modern

Tate Modern | ★★★★★

When we think of 20th century abstraction we tend to think of great male painters who divided the canvas into blocks (Mondrian, Rothko) or set colours against each other in explosions of warring pigment (Pollock). Agnes Martin’s approach was different. She ruptured the chains of figuration only to find another way of being painstaking: through the methodical, meditative construction of pattern – dots, lines, grids – on canvas. To stand before one of her paintings is to share in the therapeutic effect that creating them must have had. The mind empties. Serenity takes hold.

Bold, restless and prone to instability, Martin was everything her controlled paintings aren’t. Born in Canada to Scottish parents in 1912, she studied at a number of institutions across the US before turning to art at the relatively late age of 30, following a spell at Columbia University. She was a lesbian, a champion swimmer, an amateur mechanic and, for many years, a hermit. One day, after being found walking the streets of New York in a stupor, she was admitted to hospital and diagnosed with schizophrenia.

This stellar retrospective at Tate Modern is the first since her death in 2004. Her hermetic tendencies go some way to explaining why she wasn’t exhibited more widely, and the paintings themselves tell of solitude, or what some refer to as “oneness”. At Columbia she became interested in Eastern philosophy. “Zen” is an over-used and misused term, but it’s justly applicable to Martin, both in the way her paintings were produced and the effect they have on the viewer.

For all the regularity and repetition, Martin’s human hand always feels present. A smudged grid, a near-imperceptible bend in a line; these enliven and animate paintings that could, at first glance, have been made by machines. Gridded paintings like Friendship and A Grey Stone shimmer, projecting their orderliness into the room. Her pastel-shaded late-era paintings have an altogether different atmosphere: weightless, mirage-like, they haunt the space between colour and nothingness.

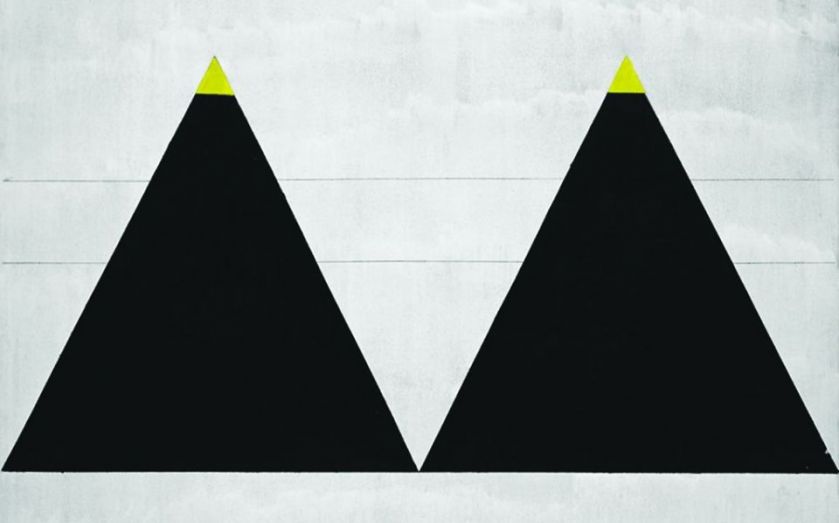

The exhibition traces Martin’s career from her early experiments with a less structured form of abstraction in the 50s to her final paintings in the year before her death in 2004. Still abstract, these late works are brighter and less restrained than the ones for which she is best known. In Untitled #1 (pictured above) snow-capped mountain peaks point skyward (to where she was headed?). White lines on black are given the enigmatic title The Sea. It says a lot about Martin that as her movement slowed and her faculties declined, she continued to defy her physical and mental state with the most intense and passionate work of her life.

TOP ART SHOWING NOW

Eric Ravilious ★★★★★

Unorthodox watercolours offer a loving glimpse of 1930s Britain at the Dulwich Picture Gallery

Sonia Delaunay ★★★★☆

This unsung genius of abstraction broke new ground with her vibrant paintings and fabrics. Tate Modern