Meet the micro nuclear reactor company hoping to decarbonise UK manufacturing

Nuclear power is typically associated with projects of vast scale, often designed and built with the intention of powering millions of homes.

However, as the government looks to revive nuclear power and replenish its ageing fleet of reactors, nimbler parties are also looking to play a part.

This includes small modular reactors – which could theoretically provide as much as a quarter of the power of a nuclear plant but an eighth of the cost – like the project pushed forward by Rolls-Royce that has secured £210m in funding.

But there are companies thinking even smaller.

US startup Last Energy, set up in 2020, is looking to roll out micro nuclear power plants.

The pitch

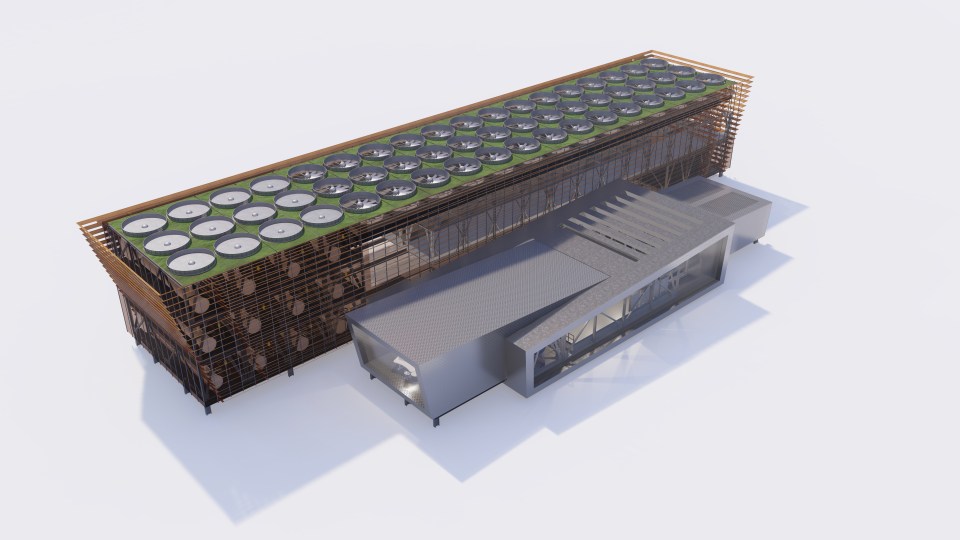

Last Energy plans to design, manufacture and operate the reactors on behalf of heavy energy users, such as factories, scientific campuses and industrial plants. It would then look to install its reactors on site and operate as an energy vendor, while maintaining ownership of the nuclear asset, selling the energy they generate to the factory under long-term energy contracts.

Its reactors are about 20MW in scale, take around two years to build, ship and set up, and cost Last Energy around $100m.

By contrast, the proposed power plant Sizewell C is 3,200MW will take over a decade to build, and could cost between £20bn-35bn, with the early stages funded by the taxpayer.

Chief executive of Last Energy UK Mike Reynolds considers its business model to be a profitable one, and no different from the tried and tested energy supply deals big industry players currently sign up to.

“Those long-term deals provide enough revenue and profits to make it worth us doing. Crucially, what they enable us to do is to go out and fundraise and privately finance the whole thing,” Reynolds said. “We don’t ask the government to support it or fund it in any way.”

The firm is also very keen to tout the green benefits of its reactors, arguing that each micro reactor could prevent as much as 79,000 tonnes of CO2 being emitted per year.

The company, one of the first of its kind, is backed by multiple investment partners including First Round Capital and Gigafund, and former Microsoft chairman David Marquardt.

Early stages

A number of UK firms are supposedly interested in what the firm has to offer. Last Energy said it has struck provisional deals with a life sciences campus, a sustainable fuels manufacturer and a data centre company, for a total of 24 mini nuclear reactors.

It declined to name the firms, however, until any of the plans are approved by UK regulators, the Office for Nuclear Regulation and Environment Agency, which require each individual design to be approved before beginning construction.

If signed-off by regulators they could generate over £11.4bn in future electricity sales, it claims.

So far, however, the company has only built a prototype of its nuclear reactor in Houston, Texas.

Reynolds said the firm is currently on the hunt for a big heavy industry customer that it could use to show its product can help decarbonise sectors with energy-intensive processes.

He revealed Last Energy is in talks with multiple potential big clients and that the first three were just the “tip of the iceberg in the UK” as it has a “very significant pipeline of opportunities.”

Limitations?

The Nuclear Industry Association (NIA) is highly supportive of Last Energy’s pitch and its mission to provide clean energy to the industrial sector.

“Smaller, more advanced reactors offer a real solution for industrial energy users looking to wean off expensive and volatile fossil fuels,” Tom Greatrex, chief executive of the NIA, said.

But there are some limitations.

Last Energy’s reactor can provide energy to generate 300C in heat, making it viable for some but not all of the UK’s industries.

Steel, for example, requires temperatures of between 900 degrees to 1,300 degrees in furnaces to operate properly.

However, production facilities for mining or chemicals, for example, would be viable.

“The problem we’re trying to solve is not grid-connected scale power. What we’re trying to solve is localised generation,” Reynolds explained. “There’s a real challenge with the decarbonisation of heat for industry. What’s the alternative? Currently, they’re burning gas. What are they going to switch to?”

There’s no doubt that the idea is still at a relatively early stage, and firms may not be prepared to sign up to what it is offering until the first projects have been successfully rolled out.

But the potential it has to help the UK’s heavy industry go green definitely means it is a firm, and concept, worth keeping an eye on.