The London Underground’s birthday celebrates 160 years of political feuds and delays

On the birthday of London Underground, Comment & Features Editor Sascha O’Sullivan looks at 160 years of delays and the fights over funding which have dogged the transport network.

In May last year, hoards of Londoners, many of them bespectacled and male, went underground to board the newly opened Elizabeth Line.

It was an opening only eight years in the making, delayed multiple times, billions of pounds overrun.

But like yesterday’s hangover, it was quickly forgotten as the purple line whizzed through Central London.

Today the Underground – and the ready-made excuse for being late to work – turned 160-years old.

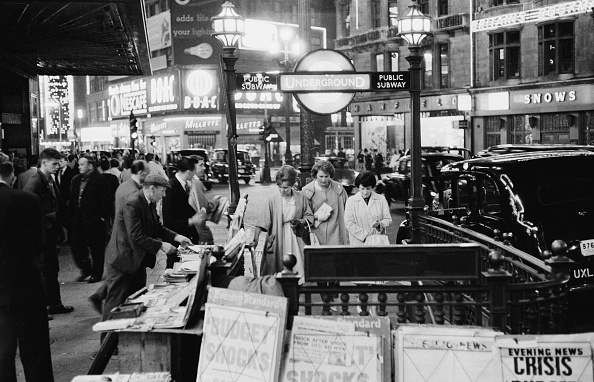

The Metropolitan Line opened on January 10, 1863, largely with the help of an American investor Charles Tyson Yerkes. Since then, the transport system has been a source of much grumbling, of envy, and of political rows.

When the pandemic kicked off in 2020, Transport for London was given emergency funding from the government to keep it alive while commuters stayed home. It ended up totalling more than £5bn.

Little did Boris Johnson and his then-Chancellor Rishi Sunak know, they were signing a long lease for a political feud that would rumble on well into last year, when City Hall and Downing Street finally knocked heads together for a long-term funding plan.

The most recent skirmish is part of a long history of disagreements.

In fact, when, in 1868, another railway firm followed the example set by the Metropolitan Line and opened what is now known as the Circle & District Line, the two owners became rivals, delaying progress on a city-wide network.

It wasn’t until 1908 when the separate companies started to work together to start a system then operating under the Underground brand, thanks largely to Yerkes, a Quaker from Philadelphia.

Now we’ve got buses, tubes, trams, a cable car across the Thames, the DLR and the Overground. And, of course, we still moan.

In the early 2000s, the Transport system was in chaos again. Paper tickets, tubes which arrived haphazardly, signal failures. If you’ve ever wondered why someone is running for the tube when the next one will be along in 90 seconds, imagine breaking into a sprint the moment you heard that familiar rumble, because the next might not be for 20 minutes.

Nick Bowes, chief executive of Centre for London, moved to the capital 23 years ago, and used to turn up at the window of Balham tube station at 10pm to get his ticket (yes, paper ticket) when there were no queues.

“We’ve forgotten what it was like, yes it’s busy, yes there is a question mark over the cost of the tube, but the fundamentals have massively changed,” he said.

“In the old days, you had no idea when the next tube would be along.”

Transport for London was set up in 2000, the Oyster was brought in in 2003, and contactless in 2014.

It has gone through a transformation, which has benefited the capital.

Passenger levels are back at 80 per cent pre-pandemic levels, after they fell to five per cent in the height of the pandemic.

It’s resilient, but as Bowes says, it is still a “fragile and delicate” thing.

Plans for the Victoria Line were hatched in1949, opened in 1968, the Jubilee line as we know not it in 1965, opened in 1979, and the Elizabeth Line was first approved in 2007.

We’ve been promised upgrades to the Piccadilly Line and the Central Line.

Personally, I love the underdog and will wax lyrical about the many, many merits of the Central Line. The lack of air-conditioning, for example, keeps you warm for free (cue, in this economy meme). But it was also responsible for more than 3.5 million lost customer hours in 2019/20.

The Underground has kept the city going because of continued investment, some of it wiser than others. Next year a mayoral election will likely put the question of funding back centre stage. In the meantime, we need to keep envisaging how we want to travel in the capital and kick off plans now because if there’s one reliable thing about the tube, it’s delays.