Liz Truss should look to former Prime Minister Anthony Eden for style inspiration

In case you hadn’t noticed, this week has all been about politics. With Liz Truss settling into The Big Job, old faces will start to fade as a fresh set of leaders jostle for our attention. And of course, the nation will have a critical eye on their sartorial choices.

Truss herself has faced a daunting level of scrutiny for her personal style. So, to compare and contrast, I’m looking back to one of the stablest political style icons of the 20th century, former Prime Minister Anthony Eden.

Eden tends to be remembered as the impatient heir of Winston Churchill, or as the Prime Minister whose tenure in Downing Street was ruined by the Suez Crisis, forcing him into resignation in 1957 less than two years after he’d taken over. But Eden was a genuine force in fashion too: he was probably the most glamorous male politician of the 20th century.

Elected to the House of Commons in 1923, it was a pivotal decade for style, profoundly influenced by the First World War. Eden’s early years would have been surrounded by the frock coats and top hats that were ubiquitous in Westminster in the Edwardian age, but they began to disappear, being replaced by the lounge suit, which became the staple, usually in three pieces.

Eden became known as one of the “Glamour Boys” of the 1930s. It was not a kind description, as it strongly implied that some of them were homosexual

As a leading politician of the inter-War period, Eden stood out. He was young, good-looking and conscious of his appeal, and became known as one of the “Glamour Boys” of the 1930s. It was not a kind description, as it strongly implied that some of them were homosexual, but it was a time when ostentatious male style was hard to separate from the suspicion of unsound sexual mores.

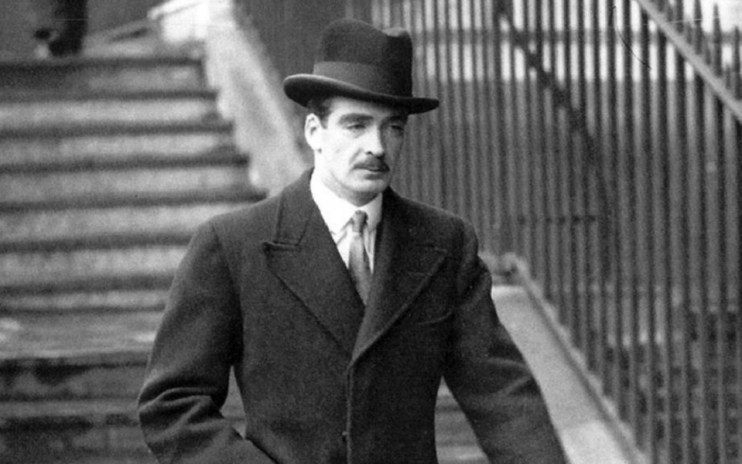

Nevertheless, Eden cultivated the image. His suits were cut with flair. Wide lapels and the double-breasted waistcoat created an impeccable silhouette. His hair was dark and carefully coiffured, and he sported a neat moustache which gave a slightly caddish air. Most of all he popularised the wearing of the Homburg, which became known for a time as the “Anthony Eden hat”.

With a curled brim and a dent in the stiff crown, it became a more fashionable alternative to the bowler hat for semi-formal dress: while a top hat was still essential for morning dress, a Homburg could set off a more adventurous lounge suit. Eden had found his great prop, and an Ameri can reporter breathlessly described his “pin-stripe trousers, modish short jacket and swank black felt hat”.

His dress sense was a carefully contrived pose. Its immaculate nature made dowdier colleagues uneasy and suspicious: one contemporary said that Eden was a mixture of his parents, “half mad baronet and half beautiful woman.”

But it gave him enduring popular appeal. He proved that the British could be handsome and stylish and could carry that reputation around the world. It is difficult not to end with a note of regret. Where are Eden’s descendents and successors in modern politics? Where are the male MPs who catch the eye either with good looks or elegant tailoring, let alone both?

Perhaps public opinion has changed and is no longer tolerant of self-conscious swagger. But it seems a shame that our leaders aim so low, craving anonymity. British tailoring is the best in the world, why shouldn’t we see more of it on our television screens?