‘I’ve never been in a faction’: Anneliese Dodds on her plan to unite Labour under a new economic platform

Labour’s new shadow chancellor had been an MP for just two-and-a-half years, before being handed the second most important job in Her Majesty’s Opposition.

Many would assume that an MP with that rapid a rise up the greasy pole of politics would have to be the consummate Westminster schemer – a modern day Harold Wilson if you will.

However, Anneliese Dodds – a former public policy lecturer – is a unique case at a unique time and any accusation of political careerism falls flat.

The Oxford East MP describes her political career as “serendipitous” and speaks about its origins with genuine modesty.

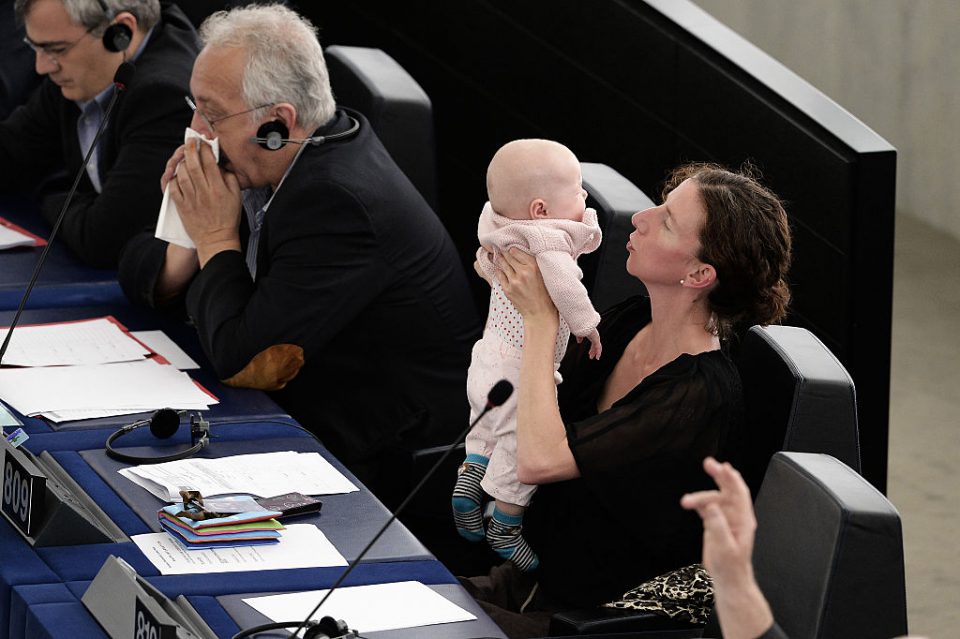

After failing to get elected at a national or local level on several occasions, she reluctantly stood as an MEP candidate in the 2014 EU election and was victorious in South East England.

“I was an MEP for a couple of years and then anticipated I would return to a previous lecturing job, but the sitting MP for where I live stood down quite unexpectedly,” she says.

“People quite often ask me for advice around [becoming an MP].

“I say well, ‘there was no strategy behind what happened to me at all’, quite the opposite really.”

Dodds’ promotion comes as a part of Sir Keir Starmer’s bid to restore credibility to the party’s frontbench, with many of the plum roles taken up by those who have excelled outside the realm of politics.

Dodds completed degrees from Oxford University, Edinburgh University and the London School of Economics, before beginning an academic career at King’s College London and Aston University.

She was handed a slot as a shadow Treasury minister upon entering parliament in 2017 and was praised for her intelligence and pragmatism.

She is also not a member of any of Labour’s oft-warring factions, which chimes with Starmer’s promise to unify the party and stop tribal infighting.

“I’ve never been part of one faction in the Labour party,” she explains.

“There are individuals who think being allied with a particular wing is necessary for them, and I respect that, but for me the biggest and most critical thing has never been internal discussion within the Labour party.

“It’s about how we can directly improve people’s life chances and that’s what I’m focussed on.”

While many will regard Dodds as a vast improvement from her predecessor John McDonnell – unlike him, she is not a creature of rigid socialist ideology – she will still have much work to do.

Despite Starmer’s positive approval ratings, it will likely take years for the public to regain trust in a party that was so thoroughly humiliated at the December General Election.

A key pillar of Labour’s push for credibility will be the party’s economic policy platform and its new architect.

The shadow chancellor will have five years to convince voters she can be trusted to manage the post-coronavirus economy.

Dodds said building bridges with the private sector and the City of London was a key part of this.

“We began that from our first day in position and found it to be really fruitful dialogue so far,” she says.

“We’re talking to many of the peak associations and trying to do that in a way that reflects business diversity across the UK and trying to make sure we have those conversations.”

She enters the job with the UK economy effectively suspended in animation and she will have to to carve out her future vision for Britain in unprecedented circumstances.

It will be a vastly different economy from that of just months ago, with many experts predicting long-term scarring in the form of mass unemployment and severely dented consumer demand.

In April, 2.1m people claimed Universal Credit – a 70 per cent increase from May – and many more job losses will follow once the government ends its furlough scheme.

“The UK economy has not been used to high levels of unemployment for some time and that will need a different policy response,” Dodds says.

Sign up to City A.M.’s Midday Update newsletter, delivered to your inbox every lunchtime

“I think there’s very little discussion in a UK context on the role of upskilling and redeployment as a result of this crisis.

“We can’t have a situation that we saw in the UK for example at the time of the pit closures [in the 1980s], we can’t have that standing back approach we saw.”

Unsurprisingly, she does not advocate another round of austerity to deal with the ballooning deficit caused by the crisis and she thinks those “with the broadest shoulders” will have to contribute more than they did after the 2008 crash.

“We need an equitable response, because we didn’t have it in 2010,” she says.

“Large numbers of UK households are lacking in resilience – a quarter of UK families only had up to £100 savings when this crisis started.

“That needs to be borne in mind when dealing with the debt that will result from the necessary measures taken by NHS, social care and so forth.”

While the new shadow chancellor may not keep a copy of Das Kapital at her bedside, her economic leanings are still fundamentally left-wing.

When asked about her priorities for Labour’s economic platform much of the discussion revolved around regional inequalities, improving public services and creating more opportunities for those from less privileged backgrounds.

While she declined to say if she would keep Labour’s 2019 manifesto promise to nationalise rail, mail, energy and water, she does advocate a higher degree of “community control” in the economy.

However, there’s also a high degree of practicality and pragmatism to her currents of thought.

She discusses at length the UK’s eternal bugbear of low productivity growth, the future digitisation of the economy and the need to prepare the private sector for a decarbonised future.

“I’m very ambitious for the UK economy – I think we have incredible strengths, truly remarkable ones,” she says.

“But to develop all of those we need to be getting the best out of all of our people.”

One potential criticism of Dodds is that she can still sound too much like a lecturer during House of Commons or media performances.

While she has a strong command of policy and has posed searching questions to chancellor Rishi Sunak in parliament, she does not yet have that killer turn of phrase that can stick in the public’s mind.

Veteran political pundit Steve Richards wrote in The Prime Ministers: Reflections on Leadership from Wilson to May that one key element linking most successful oppositions is the ability of its leading members to become “political teachers” and to create a concise narrative about their vision for the country.

If Dodds can transfer her academic teaching and communication skills into a form that is politically potent she could become a truly deadly weapon for Labour.

With only a handful of years in the game and many more ahead of her, there is no reason to doubt this could be on the horizon.