An innovation culture is about far more than shiny new tech

This summer, Airbus became the poster company for business anxiety in Britain. In June, the aerospace giant warned that it might have to consider its future in the UK if we were to crash out of the EU in March 2019 without a deal on trading, saying that the potential outcome would be “catastrophic”, throwing its production into chaos and threatening its future in the country.

A month later, Theresa May took the near unprecedented step of speaking at this year’s Farnborough International Airshow.

She sought to reassure the industry: “Let us work together to build a leading aerospace nation… a nation more innovative than anywhere else in the world, where we nurture the next generation of designers, innovators, and engineers.”

The Prime Minister’s sentiment is in the right place – and is welcome, given that the UK’s aerospace industry is the second largest in the world. But we should all be keeping an eye on Airbus, and not only because of anxieties about employment and the harm a sharp Brexit rupture might do to the reputation of the aerospace sector.

Because this isn’t just about Airbus, or aerospace. It’s about the culture of innovation in the UK.

Aerospace is widely seen as the instigator of technological change in many fundamental engineering disciplines, including sensing, electronics and communications, the use of composites, new metals and plastics, and the development of more efficient and sustainable power and energy systems.

It also sparks crossover technical development in other industries, such as F1 and energy. Moreover, Airbus alone spends £500m a year on research and technology in the UK, and has sustaining collaboration agreements with more than 20 universities across the country.

The work that it does may not always be in ground-breaking new products, but the innovation culture it fosters is crucial to the success of UK business.

Unfortunately, innovation is a word that has been flayed and sorely abused in recent years. It has become a motif for any activity, product or service considered modern and “cool”, so the word can frequently divert us.

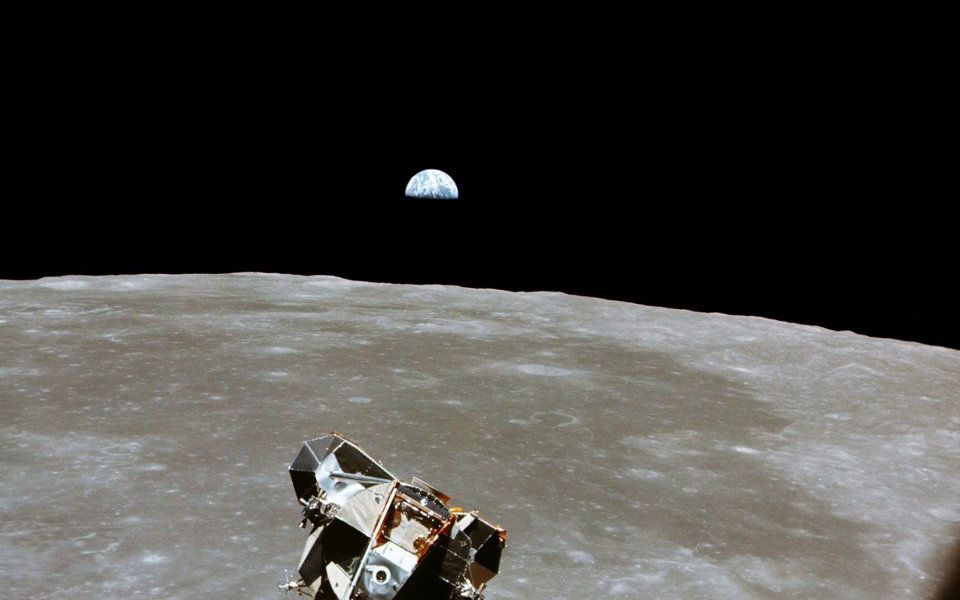

Innovation is often associated with big events like the Apollo space missions and the proverbial “giant leap for mankind”. However, the mundane sounding “incremental innovation” is just as important. It is this type of innovation which occurs on a routine basis, and is driven by market and customer demands.

Furthermore, when people talk about “innovation”, they invariably mean technology. However, there’s a much bigger picture: innovation can also be found within marketing, management practice, the arts and entertainment, architecture, services, and supply chains. And there are so many types of innovation: it can be incremental, “blue ocean”, sustainable – the list is immense.

Indeed, a definition of innovation entirely framed by technical advancement can be extremely misleading. As American social critic Arthur Schlesinger once said, “science and technology revolutionise our lives, but memory, tradition and myth frame our response”.

While we may seek change and improvement through technology, it is our human instincts that drive innovation, not the technology itself.

We are currently living through a revolution, one where technological singularity – composed of artificial intelligence, quantum computing and others still to be invented – will have far-reaching consequences for economies, societies, and cultures.

Yes, technology is certainly intoxicating, but it is not a panacea for all good innovation.

Behind the hype and the fixation with technology, innovation is really about creating significant new value that didn’t exist before.

This is something that we recognise here at London Business School.

For the past three years, we have been running the Real Innovation Awards. They were designed to highlight and celebrate the real, messy business of innovation – a process that’s a world away from what most people imagine.

Our award categories gloriously reflect this necessarily unruly approach to innovation. The If At First You Don’t Succeed Award celebrates learning through failure, while the George Bernard Shaw Unreasonable Person Award is for an individual who has shown ridiculous obstinacy to get their idea or product to succeed.

Innovation is the wellspring of change, and without a constant supply of clever, creative and fresh ways of doing things, the engine of economic progress would grind to a halt. It is the primary force of competition, of growth, of profitability, and of the creation of brand identity.

It is not simply defined by technology. Rather, it essentially refers to an entire business operation – from product development, to sales and marketing, to management.

The Airbus chiefs understand this. Our hope must be that wider influencers and decision-makers will recognise the importance of such companies as potent forces for innovation. The 6,000 aerospace jobs are important, of course, and certainly not to be squandered. But the industry’s central role in fostering UK innovation is even more vital.

John Mullins is associate professor of management practice at London Business School.