Inflation sliding and tough Bank of England means the pound will see better days

“Hope is not a strategy,” Jordan Rochester, a wonk at Japanese investment bank Nomura, said last September, referring to politicians’ attempts to revive the pound after it plummeted to its lowest level ever against the US dollar following Liz Truss’s tax cutting mini budget.

A lot has changed since then.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt raised taxes and cut spending by £55bn in November – reversing basically everything Truss stood for – then injected a £20bn boost into the economy at the budget last month.

The Bank of England has now signed off on eleven straight interest rate increases, sending them to a post-financial crisis high of 4.25 per cent.

Truss has been consigned to the fringes of the Conservative Party from holding the keys to Number 10. Same goes for her first Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng.

Sterling has undergone somewhat of a change in fortunes too. It is among the best performing currencies in the rich world so far this year, strengthening around 2.5 per cent against the US dollar.

Cast your mind back to the weeks after that haphazard mini-budget.

The City’s best and brightest were warning that the pound was on track to fall below parity with the greenback and settle there for years to come.

Nomura was first out the block, calling for the pound to sink to $0.95, mainly because of the UK’s enduring, gaping trade deficit that would’ve been worsened by Truss’s £45bn of unfunded tax cuts. Others followed.

“This is a fundamental balance of payments crisis, with politicians hoping it will eventually just calm down,” Rochester said at the time.

That gap hasn’t narrowed much, though it’s tough to yield anything from the Office for National Statistics’ wild data anyway.

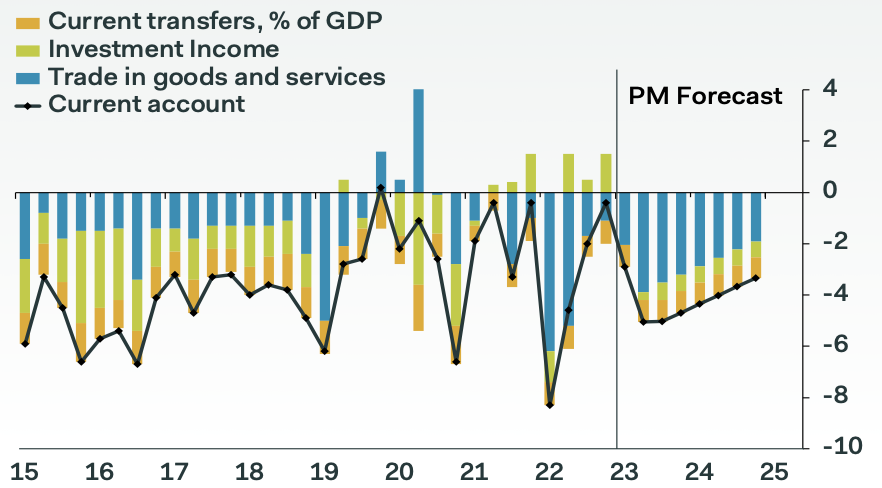

“What we can say is the UK has a current account deficit (in 2022 it averaged -3.8 per cent of GDP), but the size and magnitude is anyone’s guess..,” Rochester points out.

Pound has gained ground on the US dollar this year

When a country’s imports persistently top the value of its exports, it suffers from strong downward pressure on its currency.

A relatively slimmer supply of UK exports within the international trade network means investors have little use for pounds.

Usually this situation somewhat corrects itself by making a country’s exports more competitive, raising incentives to buy an exporting country’s currency to purchase its goods. Britain has not really benefited from that dynamic, which some blame Brexit for.

Now Nomura thinks sterling will hit $1.30 this year and $1.40 in 2024. Good news for British holidaymakers bound for New York.

It should be noted that those levels are below sterling’s long-run average. The same can be said for its performance against the euro, which it is broadly unchanged against this year.

But still, sterling is on a sunnier path than expected. Why? For similar reasons that the UK economy is outperforming the gloomy predictions at the turn of the year.

Britain’s terms of trade with the rest of the world is looking much healthier, helped by collapsing energy prices. That means it won’t have to keep borrowing large sums of cash denominated in other currencies to get its hands on foreign products.

That should also help bring inflation down quickly this year, meaning the huge erosion of sterling-denominated assets’ returns is poised to ease in 2023, raising incentives to hoover up UK stocks and bonds.

Bank Governor Andrew Bailey and co’s aggressive fight against inflation – still in the double digits at 10.4 per cent – has made UK debt a bit more attractive compared to the US and European equivalents.

Yields on the 10 year gilt are a bit higher than returns on the 10 year treasury.

Britain’s current account deficit has weighed on sterling

“If one is of the view that the Fed is done with rate hikes (as we do), then GBP/USD climbing above 1.30 this year may look to be a reasonable near-term target,” Rochester said.

Most market participants reckon we’ll get another 25 basis point increase from the Bank next month.

Undoubtedly the biggest contributor to sterling’s reversal has been the removal of the so-called “moron premium” that markets priced in after Truss’s blazing tax cutting agenda.

Fiscally, Hunt and Prime Minister Rishi Sunak are bean counters. They want the books balanced, which will improve the UK’s inflation and financial outlook.

Nagging away in investors’ minds though is the country’s awful growth trajectory. It needs to be tackled or the pound will eventually morph into an emerging market-type currency.

Here is where the inflection point lies for politicians.

Be too gung-ho with the UK’s public finances, and you risk a run on the pound. Do nothing to tackle the growth outlook, and you risk providing no incentive for people to pour cash into the country.

Borrowing to invest in the country’s creaking infrastructure could be the answer. Targeted tax cuts as well.

An election looms in 2024, allegedly. There will be tough trade offs for whoever wins.

WHAT I’M READING

Businesses will sack staff at a quicker rate as the year progresses due to consumers slimming spending in response to the Bank of England’s series of interest rate hikes. That is poised to loosen the jobs market and help bring wage growth – which raged for most of last year – down, according to a note to clients from Goldman Sachs analyst James Moberly. Watch out for today’s pay figures from the Office for National Statistics.

YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED

Britain has suffered the largest outflow of workers from the labour market within G7, the group of rich countries, since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, according to a study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. About 500,000 people have ducked out of the workforce.