Industrial Revolution: ‘History of Britain needs rewriting’ following new research

The industrial revolution was an utterly transformative moment in British history, reshaping not just the domestic economy but eventually the world’s.

Think railways, factories and mills, the rapid intrusion of ‘dark Satanic mills‘ on England’s previously ‘green and pleasant lands’.

But new research from the University of Cambridge suggests this traditional interpretation needs to be drastically revised.

“A hundred years has been spent studying the Industrial Revolution based on a misconception of what it entailed,” said Leigh Shaw-Taylor, project leader and Professor of Economic History at Cambridge’s Faculty of History.

So what really happened?

According to the research, the critical period of transition was the 17th Century, not the 18th Century.

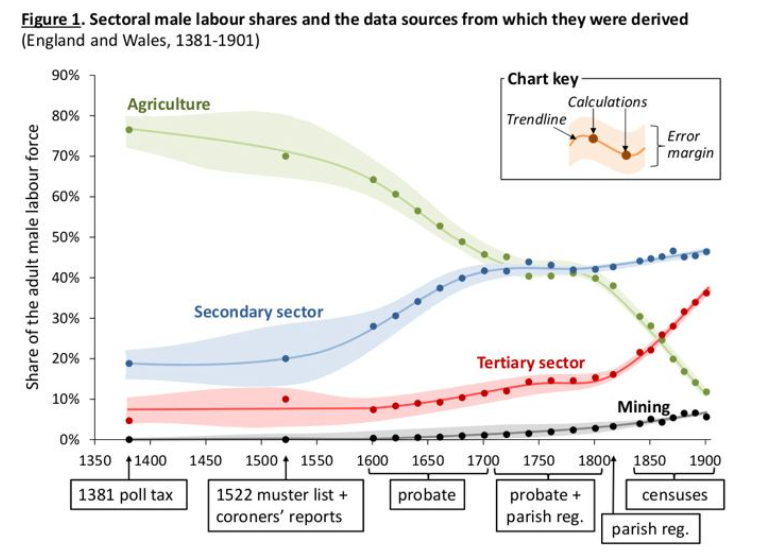

Between 1600-1700, the share of the male labour force involved in goods production rose by 50 per cent, climbing from 28 per cent to 42 per cent.

The striking increase in the secondary sector came at the expense of agriculture. The number of male agricultural workers fell by over a third to 42 per cent from 1600 to 1740.

This meant that by 1700, the share of the British labour force in an occupation involving manufacturing rather than agriculture was three times that of France.

In short, the research shows that the British economy industrialised much earlier than previously thought.

Improving productivity in the agricultural sector was a key spur for this transition, enabling more workers to move into the secondary sector without impacting the amount of food that could be produced.

But forget about factories, these early industrialists were home-workers. In 1700, half of all manufacturing employment was in the countryside, with production taking place through an intricate web of labourers working from home.

By the time 1800 came along, when the first working steam engines were just coming into use, the share of workers in the secondary sector in the economy was already flat-lining.

Indeed, during the 19th Century, many areas of the country actually de-industrialised.

For example, Norfolk was probably the 17th Century’s most industrialised county, with 63 per cent of adult men in industry by 1700. But this actually dropped to 39 per cent during the 18th Century.

So where do the dark satanic mills come in?

Shaw-Taylor noted that “industrialisation in the c17th is distinct from the ‘Industrial Revolution’ in the later c18th, when productivity really picked up largely due to the diffusion of new technologies”.

These new technologies lay behind the growth of factories and mills, islands of industrialism which developed in close proximity to the country’s coalfields.

And this concentration of industry contributed to another surprising find from the research. The service sector played a much larger role in the economy from an earlier point than previously recognised.

A large part of this expansion came from the transport sector, which had to develop in order to transport goods produced in specific areas around the country.

But it was not just transport. In the 19th Century, the size of the service sector nearly doubled with growing numbers of sales clerks, domestic staff and white-collar professionals.

At a time when the economy is struggling with its own productivity problems, could Hunt and Sunak learn anything from this period of rapid transition?

Unfortunately, Shaw-Taylor said “we just don’t know what caused the improvement in agricultural productivity in the 17th Century”.

A range of factors have been put forward as potential explanations for early industrialisation – including coal, the role of the British Empire and the impact of new technologies.

Shaw-Taylor was reluctant to ascribe causation to any one factor. “It only happened once. You can’t run controlled experiments on it, so it’s difficult to identify causation,” he said.

“But one factor seems to be that by the 17th Century Britain had an unusually unified market”.

Many European countries still had tolls on trade levied by local bigwigs. These mostly fell out of existence in England at the end of the medieval period.

Guilds were also much weaker in England than in other European countries. For example, in Leiden, guild power prohibited textile production in the countryside outside. In Sweden, no shops were permitted in rural areas until the 19th century.

“If there were to be any modern parallels, you might say access to a large single market,” Shaw-Taylor said.

For more information about the changing structure of the British workforce during the industrial revolution, go to: https://www.economiespast.org/