Global Britain: should the dramatic shift in ownership of the UK stock market be feared or cheered?

How global will Britain be in future? This is a question that polarises opinion. But while the UK still needs to define its place in a post-Brexit world, its financial markets have never been more populated with foreigners.

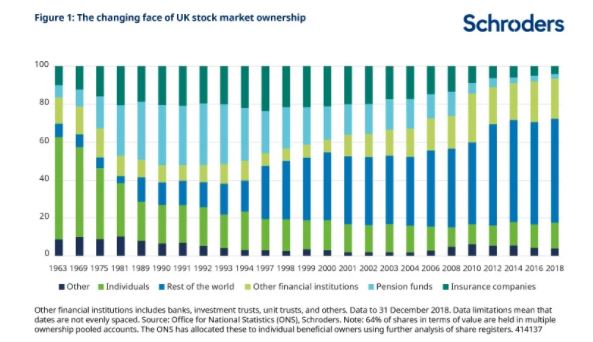

According to data from the Office for National Statistics, more than half of the UK stock market is owned by international investors, a figure that continued to rise even after the Brexit referendum.

This represents a dramatic shift compared with previous decades. In the early 1990s, more than half was held by UK pension funds and insurance companies. In 1963, more than half the stock market was held by UK individuals.

There will be those who decry the dwindling role of the individual shareholder and stoke fear over the influence that overseas investors now exert. But the story is not as bleak or as simple as that.

Are the fears unfounded?

First, while the majority of the stock market was controlled by individuals in the past, those holdings were concentrated in the hands of the wealthiest parts of society. Only an estimated 3% of the population were shareholders in the mid 1960s. In contrast, today, over three quarters of UK employees are members of a workplace pension scheme, through which they are likely to have some exposure to the stock market. The stock market has been democratised.

Second, one of the reasons that UK pension funds have become less prominent owners of the UK market is that they now invest on a much more global basis (others include a significant shift in allocations towards bonds to manage their liability risk, and greater diversification away from the stock market in favour of alternative asset classes such as real estate, hedge funds and private equity).

As recently as 1990, around three quarters of the average UK pension fund’s stock market portfolio was invested in the UK, with only a quarter overseas. Today, over 80% is overseas.

This internationalisation of UK pension fund portfolios has been mirrored elsewhere. The majority of overseas investment in the UK stock market has come from overseas institutional investors, such as pension funds. The US is the most common source, followed by Europe ex UK.

It is true that some of those overseas holdings could be tactical, short-term positions, rather than strategic, long-term ones. This could make the market more vulnerable to outflows. But there has been little sign of this so far, despite the UK having come through a turbulent period following the Brexit referendum.

The share of the market held by international ownership has continued to rise during this period. Although sentiment studies have shown the UK stock market has hardly been flavour of the month, fears of a rush for the exit have proved unfounded. Overseas owners have not been as flighty as some doom-mongers portrayed.

Furthermore, rather than viewing the shift in ownership from individuals, to pension funds and insurance companies, to overseas investors as multiple changes, it would be better to think of them as only one: a shift from individual ownership to institutional ownership.

UK pension funds and insurance companies replaced individuals and have themselves been largely replaced by international institutional investors.

This trend towards institutional ownership is a global one that has affected all markets (with the exception of some emerging markets).

Discover more from Schroders:

– Learn: Can asset management’s Covid-19 response help regain public trust?

– Read: Think short-term for lockdown but not for investing

– Watch: How climate change could affect your investment returns?

What effect will it have on society?

So the real question is whether the shift away from individuals making direct investments in individual stocks towards institutional investors doing that on their behalf is good or bad. Who is the better steward?

One popular view is that individuals are more likely to be engaged investors, as they form a personal connection with the companies in which they invest. That they have a sense of ownership rather than of financial investment alone. This can be contrasted with today’s environment, where those doing the investing (such as asset managers) are often several steps removed from the end individual on whose behalf they are managing money.

However, this image of engaged individual shareholders represents a misunderstanding of how individuals and institutions exercise their rights and responsibilities as shareholders in practice. Although individual shareholders who are highly engaged at the individual company level do exist, they are in the minority. Studies have shown that individuals cast votes representing less than 30% of the shares they own.

There can be practical reasons for this. For example, individuals normally hold shares via nominee accounts, where the nominee’s name (such as their stockbroker or online investment platform) is on the share certificate rather than the individual’s. This makes many aspects of share ownership more efficient but it does mean that individuals usually have to make a request if they want to vote, which makes the process much more cumbersome. The UK’s Law Commission has recently released a scoping paper looking specifically at the problems with and potential solutions to these challenges.

In contrast, institutional investors vote on over 90% of their shares. As institutional investors typically have much larger stakes than the average individual investor, they also have more clout to effect change at the companies in which they invest.

In this sense, the shift toward a more institutional shareholder base can be seen as a positive development. This is the third reason why fears over the changing ownership of UK stocks are unfounded.

Of course, this does not mean that individuals are disengaged with how their money is invested. For example, 57% of respondents to Schroders’ 2019 Global Investor Survey (a survey of over 25,000 people, from 32 locations around the world) said that they would always consider sustainability factors when selecting an investment product.

Investors increasingly care about how their returns are generated as much as the level of those returns. Day-to-day engagement with individual companies, however, is delegated to the investment manager that individuals choose to partner with.

Stewardship: more than a box-ticking exercise

However, that does not mean that everything is perfect. Voting, while better than not voting, is not the only measure of shareholder engagement.

Many institutional investors outsource the thinking on how they should vote to external third parties, known as “proxy voting advisers”. Some probably do whatever these advisers recommend with scarcely a second thought. There are practical reasons for this. There are around 3,000 companies in the MSCI All Country World index, with the smallest company being only 0.00002% of the index. It is simply not possible for anyone but the most well-resourced investors to cover such a large number of companies, each with its own set of shareholder resolutions to be voted on, effectively.

Voting is also only one part of stewardship. Behind the scenes engagement to positively influence corporate behaviour is just as important, if not more so.

It is important that asset managers, while seeking to manage resources, do not relegate stewardship to a box-ticking exercise. It needs to be an integral part of the investment decision making process. Unchecked, risks could build up, and put money at risk for the individuals they are ultimately managing on behalf of.

Institutions are accountable

Ownership of the UK stock market has clearly changed out of all recognition in the past 55 years. Institutional investors, many of whom are based overseas, now dominate.

However, when you follow the money from these institutional investors to the ultimate beneficiaries of those investments, you are still likely to end up with individuals. For example, a pensioner is the beneficiary of a defined benefit pension plan; a policyholder the beneficiary of a life insurance contract; a saver the beneficiary of an investment fund; and students the beneficiaries of a university endowment.

Today, the responsibility to be effective stewards of companies listed on the UK stock market lies squarely at the door of institutional investors.

Their greater propensity to fulfil their duties and vote on their shares should be reassuring. However, there is a big difference between stewardship as a box-ticking exercise and effective stewardship.

Individuals may be several steps removed from the companies in which their money is invested, but that should not prevent them from holding to account those who have been entrusted with that responsibility.

– For more visit Schroders insights and follow Schroders on twitter.

Important Information: This communication is marketing material. The views and opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) on this page, and may not necessarily represent views expressed or reflected in other Schroders communications, strategies or funds. This material is intended to be for information purposes only and is not intended as promotional material in any respect. The material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. It is not intended to provide and should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this document when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of an investment can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed. All investments involve risks including the risk of possible loss of principal. Information herein is believed to be reliable but Schroders does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Some information quoted was obtained from external sources we consider to be reliable. No responsibility can be accepted for errors of fact obtained from third parties, and this data may change with market conditions. This does not exclude any duty or liability that Schroders has to its customers under any regulatory system. Regions/ sectors shown for illustrative purposes only and should not be viewed as a recommendation to buy/sell. The opinions in this material include some forecasted views. We believe we are basing our expectations and beliefs on reasonable assumptions within the bounds of what we currently know. However, there is no guarantee than any forecasts or opinions will be realised. These views and opinions may change. To the extent that you are in North America, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management North America Inc., an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Schroders plc and SEC registered adviser providing asset management products and services to clients in the US and Canada. For all other users, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management Limited, 1 London Wall Place, London EC2Y 5AU. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.