Donmar Privacy play reveals all

THEATRE

PRIVACY

Donmar Warehouse | By Alex Dymoke

Four Stars

“IN 21 YEARS of invading people’s privacy I’ve never found anybody doing any good… Privacy is for paedos. Privacy is evil.” This speech by former News of the World hack Paul McMullan delivered to the Leveson inquiry is quoted verbatim in the first act of James Graham’s toweringly ambitious yet sprightly new play Privacy. It drew deep, hearty laughter, as if McMullan had argued himself into a corner of comic absurdity, but the truth is, at a time when it’s normal to broadcast everything from your idle thoughts to your relationship status, this is how many people feel. When confessionalism is the mode, breaches of privacy seem vaguely, not viscerally, wrong.

Graham starts with this uncertain sense that privacy is perhaps – possibly, probably, surely – an important thing. He then takes the concept, shakes it, unfolds it, turns it upside down, holds it up to the light and Googles it, until the vague sense of privacy’s importance solidifies into something more certain.

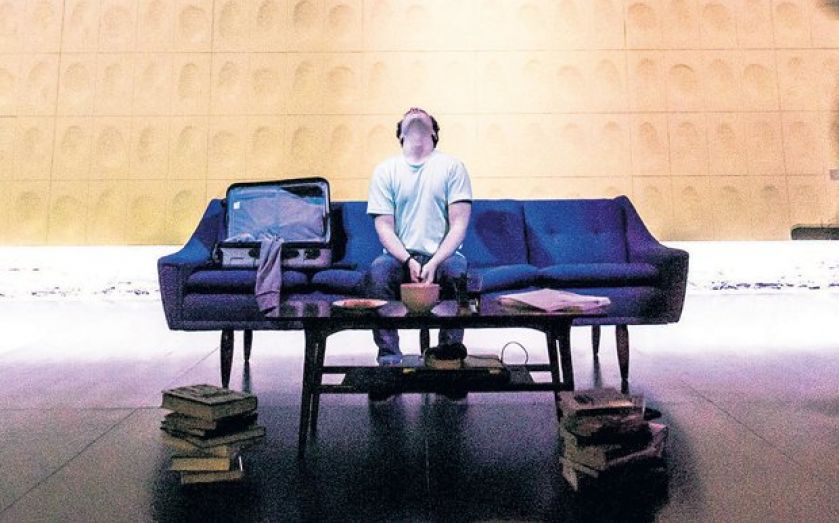

It starts in the ambiguously private/confessional setting of a psychotherapist’s consulting room. Our protagonist is thinking of writing a play about privacy, and over the next few hours we’re taken on a journey through his research process. Five other actors intrude on his therapy session, voicing semi-verbatim interviews with a wide range of people, all of whom have some stake in the privacy debate. There’s Edward Snowden, Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger, various senior civil servants, an “anonymous high-ranking judge”, Paddy Ashdown, William Hague, Shami Chakrabarti and others. We also hear from people from the commercial sector including Clive Humby, inventor of the Tesco Club Card, who reveals just how valuable our online footprint is.

We get a panoramic view of the ethical issues, from online marketers subtly guiding us down certain lucrative channels, to the NSA snooping on emails regardless of whether you’ve done anything wrong. The revelations are relentlessly shocking. Audience-members gasped when Humbly reveals a woman’s supermarket buying habits can indicate whether or not she is pregnant – even before she’s taken a test. Also eye-opening are the intimate details data-marketers can find out about us from our social media profiles. Facebook can get a decent idea about whether a relationship will still be going in a year’s time based on the language used in private messages. The dizzying breadth of information can’t help but diminish the drama, but the revelations are dramatic enough in themselves.

The internet may have been used for unprecedented intrusion, but it has an affable side, too, a quick-wittedness and an ironic charm that the play taps into. Graham and director Josie Rourke do not linger in the same place for long, offering a bombardment of jokes, stimuli and ideas that keep you breathlessly transfixed for all of its two and a half hours.

Through his sensitive, introverted protagonist (played by a brilliant Joshua McGuire) Graham is able to demonstrate the value of privacy in real terms. For that reason, even though it sometimes feels more like a madcap presentation on privacy than a play, the importance of Graham’s achievement cannot be questioned.

FILM

TRANSCENDENCE

Cert 12a | By Alex Dymoke

One Star

CAN a computer have a personality? I’m not sure, but on this evidence it certainly can’t have a sense of humour. This film about artificial intelligence gets stuck in a mire of confused computer-ethics, incomprehensible techno-babble and – rather embarrassingly, given the fascination with computers – terrible special effects. It’s not short of ambition, but fails to grasp a single one of the many Big Ideas it grapples with. For all the techno-philosophising, its intelligence is completely artificial.

Since when did computer nerds start being played by Johnny Depp? His Will Caster is a Steve Jobs-style visionary convinced that nano-technology and artificial intelligence can remedy the world’s problems. When he’s shot by a group of “neo-luddite radicals” his wife/PA/colleague (played by Rebecca Hall) uploads his personality onto a giant computer with the help of friend and business-partner Max (Paul Bettany).

Depp is woefully miscast as an evil computer scientist; implementing his plan from behind a computer screen, he reminded me more of when my friend used to Skype me from a Goan internet cafe on his gap year. Depp’s isn’t the only sub-par performance. Third-wheel Bettany wears the same terrified facial expression for the entire film. It’s like he’s crashed. Someone should try turning him off and on again. Rebecca Hall is better, but her valiant attempt at giving her character a full range of emotions jars with the rest of the film: real people look weird in this confected world.

Transcendence liberally helps itself to the worst parts of human nature (illogic, a tendency to act irrationally) and the worst parts of computers (inanimateness, an inability to sustain authentic relationships) to create a film so staggeringly unenjoyable that I wanted to hack into my own mind and delete any record of having seen it.