Boris has a war to fight, and he’s going to need all the friends he can get

“Every time a friend succeeds, I die a little.” Epigrammatic prose from the US patrician, Gore Vidal.

The line serves as a cautionary note on how to lose friends and not influence people — one that another talented communicator of our time, the Prime Minister, might want to heed.

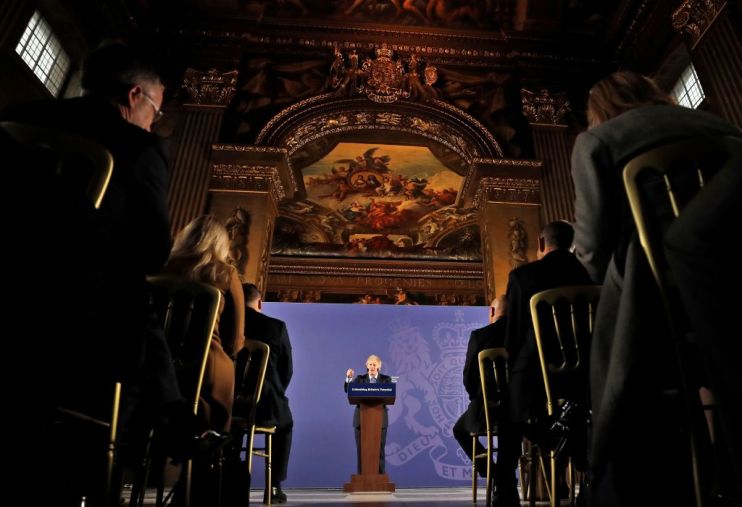

Boris Johnson went to bat last week. In a keynote speech in Greenwich, he used full rhetorical flourish to call time on Britain’s remaining doubters and to tout a free trade tirade under the banner of “unleashing Britain’s potential”.

You might have been forgiven for expecting him to open with a toast to absent friends, as so many of the usual suspects hadn’t made the guest list.

Make no mistake, this was no conclave of the cardinals of commerce. Gone were the reactionary forces of the CBI and the Institute of Directors (IoD), to be replaced by a new reformation — a rave of too-cool-for-school, free-trade-loving, breakthrough businesses.

The hurt of friends out of fashion is all too clear. The IoD’s director general, John Geldart, opined that: “businesses are less interested in the rhetoric than they are with the practical implications of the government’s approach”.

But nothing seems to get the goat of this government more than the idea of business as usual, and such wincing words of woe from the uninvited will embolden the view that pessimism is Britain’s fifth column.

Rather, the message is that this is a new era of progress through struggle. And without struggle, it’s not worth doing.

At the energetic epicentre of this is the idea of the “blob”, a word much in favour with the Prime Minister’s adviser, Dominic Cummings. You might remember it from his time attempting to reform the Department for Education. It aims to capture a catch-all vision of the reactionary forces that hold the country back. The blob is the enemy.

Throwing down the gauntlet of leadership, and spotlighting the lack of it, is the playbook to beat the blob. Hence the Prime Minister’s puncturing point that “free trade is being choked — and that is no fault of the people, that’s no fault of individual consumers, I am afraid it is the politicians who are failing to lead.”

We’ve heard this rhetoric before. The entire General Election campaign was fought on the premise that the Westminster political class had failed to demonstrate leadership. Now it’s the turn of others to feel the force of that approach.

At home, this game-plan means sacking off defeatist establishment doubters like old-school business groups or the august voices of BBC Radio 4’s Today programme (ministers have been instructed by Cummings to boycott it, along with other well-known TV and radio shows).

Further afield, it speaks to the ultimate battle royale to come: the showdown with the European Union. General quarters, all hands to battle stations.

On the face of it, the Prime Minister’s speech was swamped with a cacophony of call-outs to our “European friends”. But the political digs demonstrate that he expects little, that the enemy at the gates of this speech is Brussels, and that our “European frenemies” is his real refrain.

And while the speech was an aria to commercial activism and Britain’s historically globalist outlook — evoking the Vatican, Michael Angelo, and the “gorgeous and slightly bonkers scene” on the ceiling of Greenwich above him — we should not lose sight of the context.

Yes, it was a eulogy to the power of markets to deliver life-enhancing innovations and to lift people out of poverty. As such, this was Johnson’s first big pro-enterprise set piece, and will be greeted with relief that the government has given at least some billing to the idea that wealth creation and entrepreneurship need to be in rude health if the post-Brexit project is to prosper. We have heard precious little of that since the election.

But much hangs in the balance. The calm delivered by the return of short-term confidence is tempered by the stormy uncertain prospects of long-term change.

A technicolour future awaits, for some offering the optimistic certainty of opportunity, and for others the obstruction of insurmountable obstacles.

It is also clear that, right now, this is a government that is defining itself at least as much by who it stands against as who it stands with.

Gore Vidal also said: “It is not enough to succeed. Others must fail.” His life of bitter feuds was perhaps the ultimate testament to the limitations of this approach.

But it was another great American, the sports marketing supremo Mark McCormack, who made perhaps the more pertinent point: “All things being equal, people will do business with a friend; all things being unequal, people will still do business with a friend.”

For Boris to win his war, he will need the love of friends.

Main image credit: Getty