The artful dodger: Prolific forger Mark Landis gave all his counterfeit paintings away for free

Mark Landis was 30-years-old and living alone in San Francisco when, on a whim, he decided to become a museum benefactor. “I had been seeing things on TV about wealthy philanthropists giving pictures away to museums in memory of people. I wanted to show my mother that I was doing well, I wanted to show her that I was doing something for her memory. It was an impulse.”

Landis is 60 now but he sounds two decades older. He loves classic movies, and barely a sentence passes without a reference to some golden age actor or film. He wouldn’t look out of place in a movie himself: that intense, blue-eyed stare, his right ear sticking out a little further than the left. You can imagine him shuffling around some world dreamed up by the Coen brothers.

“How are things in swinging London?” he asks when I call his home in Laurel, Mississippi. Landis’ dad was a naval officer and he spent three years living in Swiss Cottage as a boy in the 60s. His time here was happy, but his childhood often wasn’t. A physically weak, intellectual boy, he felt he was a disappointment to his father, whose death prompted a breakdown which landed in him in psychiatric care. Part of his treatment involved art therapy, during which he discovered he was a technically gifted drawer. He found it easy to copy classic works out of books and one day, thinking of his mother, he copied a Maynard Dixon painting of a native American, added the artist’s signature, and delivered it into the hands of a curator at the Oakland Museum of California.

“If the guy had just showed me the door straight away I would never have gone on to do the things I did. But everyone was nice,” says Landis. “They treated me like royalty.”

Over the next 25 years, Landis went on to donate hundreds of forged paintings to museums across America. They weren’t of a high quality – he describes himself as impatient, and liked to “finish them by the time a movie is over” – but they were good enough not to rouse the suspicions of whoever was working in the museum that day.

Detail from Houses Along a Canal by Stuart Davis (c 1914-18). Real painting on the left, Landis copy on the right

Often the paintings would be found out within a week, but whenever a curator tried to get in touch to break the awkward news that the work he had so generously bequeathed was a fake, they found him gone, vanished without a trace.

When delivering his paintings Landis adopted different aliases. He borrowed names from auction catalogues and his extended family, but most of the time he would visit museums as a Jesuit priest. “I wanted to be a priest when I was a teenager. I admired Father Brown [the GK Chesterton character]. And I thought a wealthy family would have a priest in the family so it made sense.”

At first his mother was impressed by the thank you letters he assiduously forwarded onto her, but in 1988 he fell on hard times and had to move back home. Living with his mother and step-father, it was hard to maintain the charade. “It impressed my mother the first time, but mothers just know. She never said anything, but she would let me know: if I was leaving early in the morning to catch a plane [to bequeath more forgeries to museums]… she would give me this look.”

His mother caught on, but the law never did. As Landis never asked for money for a painting, or took advantage of the tax breaks offered to collectors to encourage them to loan artworks to museums, he never committed a crime.

According to Renaissance theoreticians, a great work of art must display “invenzione”, a creative spark that occurs in the artist’s mind before he or she has put pen to paper or dipped the brush in the paint. It is this that most separates master forgers from the real great artists, says author and professor Noah Charney. “Most forgers have tried and failed to be an original artist and forging is plan B.

One of the exceptions is Michaelangelo. He worked as a forger first and then became a pretty good artist. In terms of physical execution, forgers can be very good but they’re missing that touch of genius – i.e. conceiving what they are going to create – which makes them a step down from the artists they imitate.”

In his book The Art of Forgery, Charney draws up a profile of a typical art forger. “For most crimes, money is the primary motivating factor, but we have a unique set of circumstances in art forgers: an element of passive aggressive revenge at the art trade or art community in general. Most begin forging because they failed to establish a career as an original artist and have been dismissed or rejected by the art establishment,” says Charney.

“Forgery is a way to stick two fingers up at the art world. The benefits for the forger are twofold: first, if they can pass off their work as successfully as a famous artist it suggests that they are as good as that artist, and secondly, it also shows the expert who dismissed their original work to be foolish, so it’s double revenge. Thats the primary motivation for why most of them first turned to art forgery. For most, money is a secondary factor, although it might give them a reason to continue with it.”

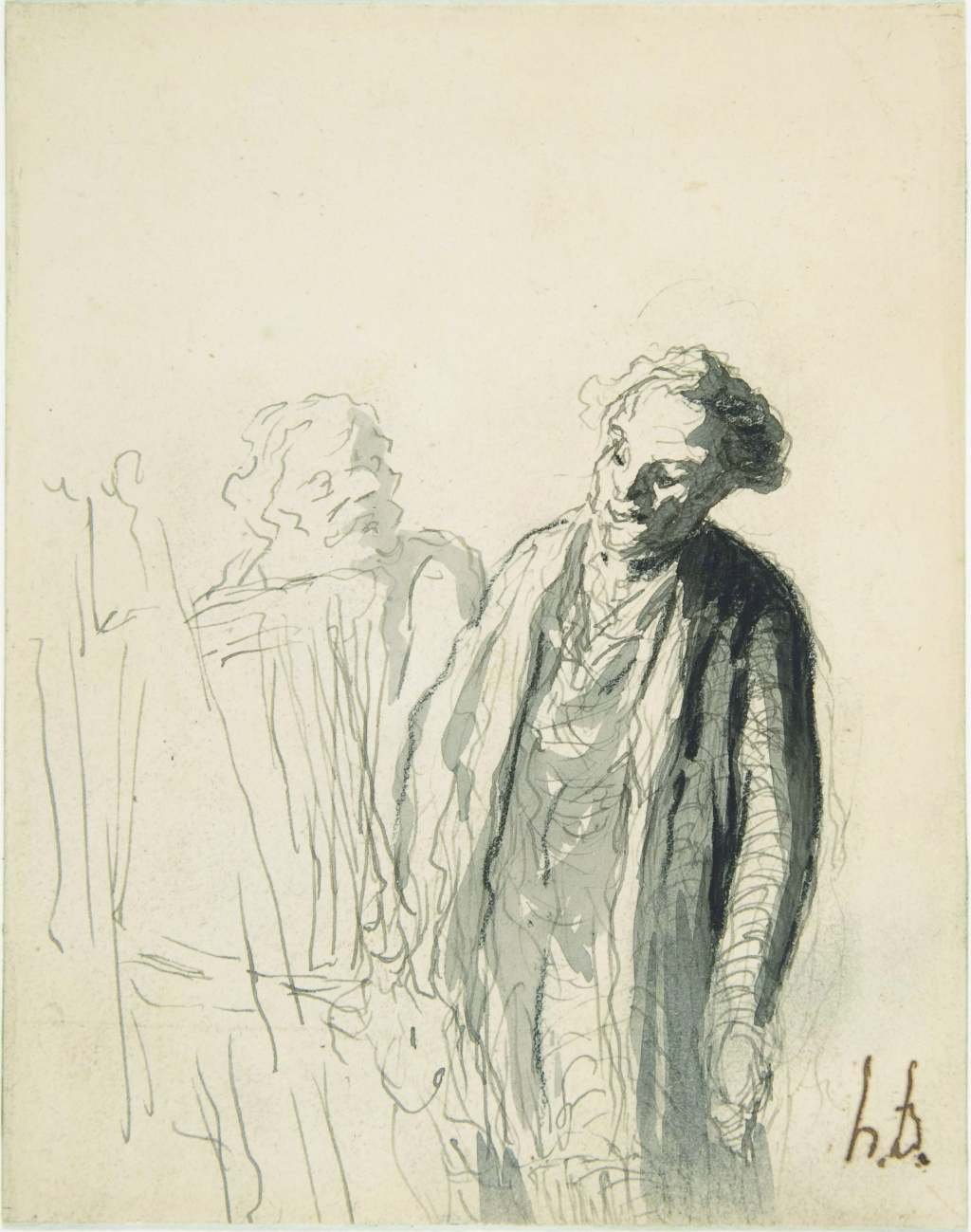

A drawing by Landis in the style of Honoré Daumier

Although money was never a motivating factor for Landis, he clearly doesn’t match Charney’s picture of the typical forger. “He’s a real extreme because he’s someone who did it not for revenge, not for money, who doesn’t seem to ever have actually committed a crime.”

“In order for a forgery to be against the law it has to defraud someone or an institution. Landis never accepted any money or any tax breaks. He did it for the joy of feeling socially accepted for the few hours when he was being thanked by an appreciative museum for donating work that seemed real. It never looked real long enough to fool anybody beyond a second look.

No one was damaged in any way, he didn’t actually break a law, so he is a successful criminal who never committed a crime.”

A detail from an authentic Daumier drawing

After the death of his mother five years ago, Landis stopped being so careful. He hopped in the big Cadillac she bought before she died and drove around America on a bequeathingspree donating dozens of pictures to galleries in honour of her memory.

Museum workers began to notice an odd man delivering poor-quality fakes to museums, and one curator in particular, Matthew Leininger from Oklahoma City Museum of Art, made it his personal mission to find and take the Jesuit forger to task.

Leininger was on duty in the museum when Landis hand-delivered a watercolour by the French Fauvist artist Louis Valtat. He immediately placed it on the wall next to a Renoir. Soon after, the curator received an additional five works by post, including paintings ostensibly by Paul Signac, the 19th Century French artist.

Leininger researched the painting and found that the exact same one had been submitted to the Savannah College of Art and Design in Georgia with the same credit line thanking Mark Landis. He sent word around to other museums, and was immediately inundated with messages from other curators who had received forgeries from Landis.

Landis first realised he was in trouble when he looked at the Wikipedia entry for his home town in Mississippi. It was a page he visited often, scrolling down the “notable residents” and viewing with a mixture of pride and guilt his name followed by the description “art dealer and philanthropist”. Until one day he checked it and, as he says, “It had something negative on it”.

“I have poor self esteem. I always have. You’ve seen a picture of me. I’m not too good-looking. I got dealt a bad hand… If ever someone in the Royal Family complains in the paper, don’t feel sorry for them, because being treated like royalty is wonderful. I liked it so much I just got used to it.”

As more people got wind of what he had been doing Landis’ ignominy turned into fascination. People wanted to know about the shadowy figure donating forgeries to museums across America. Two film-makers from New York got in touch wanting to make a documentary, and so began the next unexpected chapter in Landis’ life.

“They are my best friends in the entire world, there’s nothing I wouldn’t do for them,” says Landis of Sam Cullman and Jennifer Grausman, whose documentary, Art and Craft, was a minor success in America. The documentary was initially intended to be a meditation on authenticity and authorship in art, but upon meeting Landis, Cullman and Grausman decided to focus on the man himself – a true one-off.

The Art of Forgery by Noah Charney is out now, published by Phaidon. Buy it for £19.95 from phaidon.com.