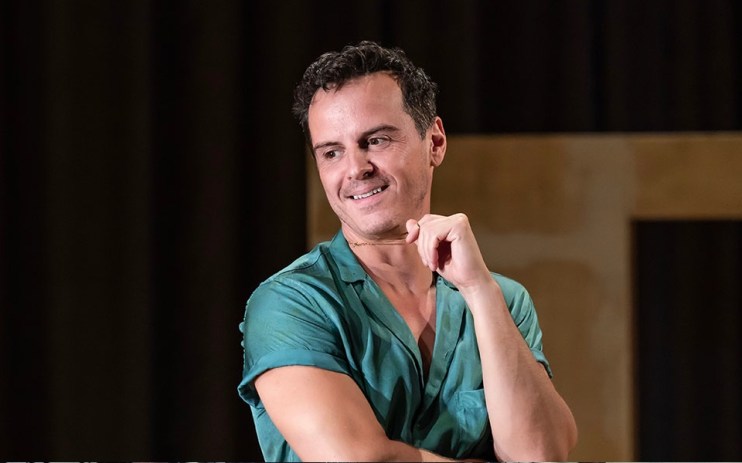

Andrew Scott shines in strange one-man Vanya

Vanya, a one-man play starring the inimitable Andrew Scott, answers beautifully a question that nobody ever asked: what if Chekhov’s most enduring play were transplanted to Ireland, and all the roles were played by a single actor?

It’s a strange idea, as much a thought experiment as a piece of drama, but one that’s anchored by an astonishing performance from an exceptionally talented actor.

It all takes place in a stark, crummy-looking bedsit, a freestanding door frame dominating the centre of the stage. The core elements of Chekhov’s play remain the same: an extended family live together in a crumbling country pile, all suffering from a debilitating ennui and all lusting after either the brooding, alcoholic doctor Michael or the wistfully beautiful Helena.

Sonia (the names are all Anglicised, or perhaps Gaelicised), the “plain” daughter of filmmaker Alexander (the job titles have also changed), mooches about the stage, switching the theatre lights on and off and brewing ‘herself’ a cup of tea.

She remembers the arrival of Michael and Scott disappears behind the door, entering through it a different human being, his voice and mannerisms uncannily changed. So it goes throughout the play – for each character, Scott morphs chameleon-like into someone new, each one with motifs and ticks that make them immediately recognisable. A distracted Helena fidgets with her necklace, a nervous Sonia fumbles with a dish cloth, the louche, dishevelled Ivan toys with his sunglasses. That the whole thing doesn’t descend into unintelligible nonsense is testament to Scott’s physical acting.

It’s also very funny, leaning into the absurdity of the set-up with knowing winks to the audience; at one point Scott gestures into an empty corner and says of a character whose role is essentially cut from the play: “Oh, I forgot about you sitting over there!”

And there is sex. Scott on Scott action. Here even an actor this talented struggles. There is gusto to his short, sharp rut against a door frame, reaching behind to grab his own buttocks as he thrusts into nothingness. But it’s very silly, and surprisingly unsexy for a man best known for playing Fleabag’s Hot Priest.

The play races along to the third act climax, when Chekhov’s gun is inevitably fired, but after this it loses its way. The quiet final scenes aim to bring out the mundane tragedy at the heart of the play – that most of us lead unfulfilling lives – but the electricity that’s built up in the first hour is grounded by that gunshot and I found myself noticing more and more the high concept and less and less the message.

In lesser hands, this would be an unbearable way to spend an evening. With Scott as its driving force, it’s a fascinating curio, Fringe theatre elevated to the level of high art. I’m not sure that casting one person in all the roles of an Irish take on Chekhov brings any fresh illumination to the play but it’s a wild ride nonetheless.