UK startups are built on immigrant talent, the UK will fail if it forgets this

The UK is talking the talk on becoming a science superpower, but we need cash and a focus on attracting international talent if we want to compete on the world stage, writes Jack O’Meara

On a Tuesday afternoon in mid January, science, innovation and technology secretary Michelle Donelan delivered a speech at an East London innovation centre. In front of the assembled crowd, she announced her ambitions to turn the UK into a “powerhouse of growth” and a “scale-up superpower” by tapping into the potential of companies on the verge of expansion.

Few entrepreneurs, myself included, wouldn’t be excited by pledges to “crack open the powder-kegs of UK investment”. But if Donelan wants to see the UK ascend to scale-up superpower status, it’s time to widen her focus from the few, elusive tech unicorns and instead consider practical reforms to raise the tide and elevate the prospects of the entire science and tech startup community.

Cash is king

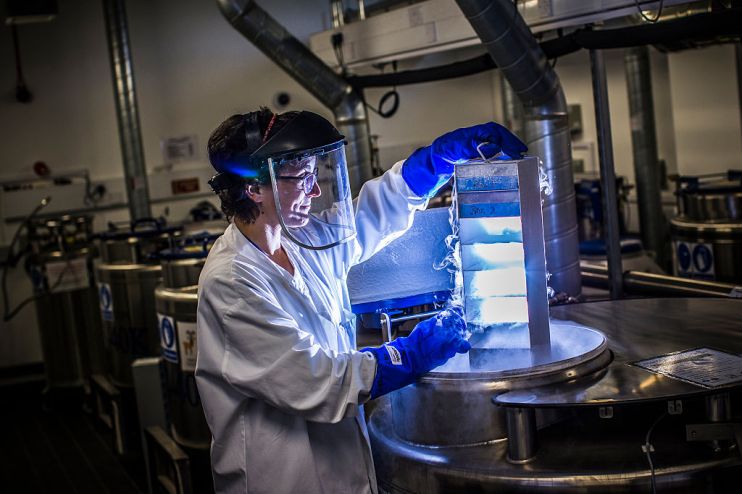

Scaling a life science startup is an extremely capital-intensive operation. World-class research and development, leveraging cutting-edge techniques and technologies in the advent of breakthrough medicines, is not cheap.

As a result, life science companies in particular have a tendency to shift operations to the US to be close to investment. Capital has a gravitational pull for fledgling companies. At the biotech startup I lead, Ochre, we recognised this and raised our early financing in the US, but we were intentional about building an R&D presence in the UK. We needed to find investors who had the deep pockets needed to pursue a novel and ambitious approach to liver disease R&D, who are largely found in the US, but given the wealth of talent and lower cost base in the UK, it seemed a no-brainer to set up operations here.

As companies scale, however, there is a tendency to be lured across the ocean by the funding opportunities, talent base and enthusiasm for high-risk innovation of the US. I have watched companies we once shared lab space with pack their bags and relocate to Boston. This ultimately drains the UK ecosystem of both the company scaling expertise and the return on investment to redeploy into the sector.

How can this draining of talent and innovation be halted? As with many things in life, it comes down to cash. The same rich funding and investment opportunities available in the US need to be cultivated here in the UK. The promise of more government grants is encouraging, but these will necessarily be limited and capped. We need to incentivise larger pools of capital to invest in the UK.

The reversion of cuts to R&D tax credits and recent Mansion House reforms to pension investment policy are a step in the right direction, though we need a clear strategy for how this capital is going to be intentionally and responsibly deployed. There are great fund managers in the UK. But we need more of them. We should find creative ways to lure capital and expertise towards this side of the pond, in the same way US investors have managed to pull companies westward.

UK startups have been built on immigration

I cannot emphasise enough how important it is to the future of the UK’s life sciences sector – and to the UK economy – that our visa and immigration policies are designed to foster entrepreneurship and the flow of talent, rather than to dissuade it. The best science is not carried out in national silos – this is a high-skill sector that depends on the seamless flow of talent, expertise and experience. The UK currently has more international unicorn founders than any other European country, and, according to a 2023 report, 39 per cent of the UK’s fastest-growing startups have at least one immigrant co-founder.

The majority of my company’s UK team were once international students here, including my co-founder, but it’s getting harder to recruit talent as, by forbidding foreign students from bringing their spouses into the country, and attaching high costs to visas, the UK is effectively pushing potential entrepreneurial talent to study and ultimately settle in other countries.This simply does not make sense and must be urgently reconsidered.

UK must look outside usual channels

In January, Donelan also announced the creation of a ‘Scale Up’ forum that will bring together stakeholders from the public and private sectors and bridge the gap between founders, investors and the government. For this to have an impact, the department for science, innovation and technology needs to put in serious legwork to make the forum truly representative of the UK science and tech entrepreneurship community.

This means looking outside the usual channels to recruit participants, creating regional branches to address the unique challenges of different geographies and working with the groups that already exist to champion the interests of underrepresented entrepreneurial communities. Diversity fuels innovation, and fostering diverse, challenging perspectives is a necessary ingredient for sustainable growth.

I’m proud to have built a thriving life science company in this country, and to have had the chance to work alongside so many talented and passionate people in the process. But I know there are so many more founders who, with the right funding, support, regulations and partnerships, would build something equally promising. By digging deeper and wider funding pools, welcoming talented people and their families, and committing to nurture the next generation of innovators, technologists and scientists, the UK has all the right ingredients to be on the fast-track to scale-up superpowerdom.