The miracle of Robben Island: Why Mandela matters internationally

AFTER the oceans of ink that have rightly been spilled these past few days lauding Nelson Mandela, is there anything left to say?

Perhaps just this. Those of us who analyse the world for a living think in terms of large macro phenomena: rates of GDP, demographic trends, military capabilities, national political cultures. We are right to do this, as these massive forces generally account for the global current that propels our world on its way. However, spending all our time focusing on the Olympian view renders it terribly easy to forget the human forces which, like sub-atomic particles, actually comprise and in their millions determine the larger, historical trends we cover.

I think that is precisely why Mandela still matters to people, and mattered internationally in the remarkable era of the late 1980s to early 1990s. The particulars of what Mandela overcame are well-known but bear repeating. As commander-in-chief of the African National Congress’s (ANC) armed wing, plotting against the diabolical apartheid regime in South Africa, Mandela was caught and eventually convicted in 1963. He was not to see the outside world again until 11 February 1990, when he was 71.

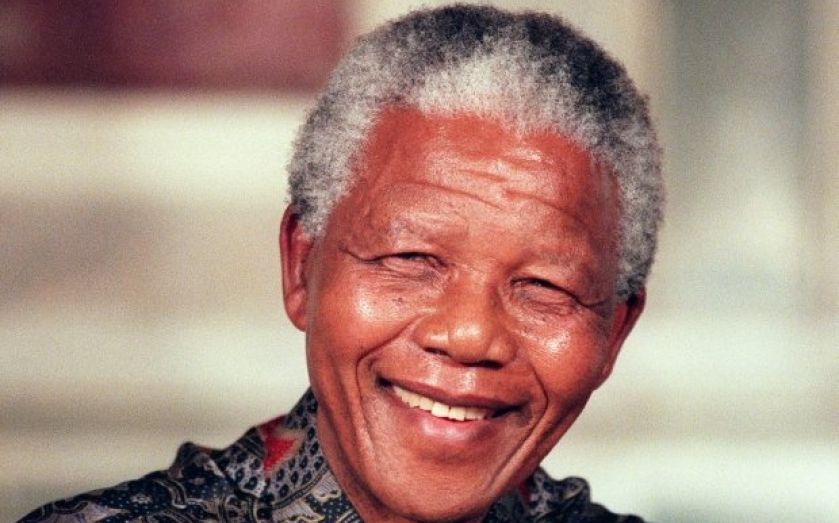

He spent the lion’s share of that time, 17 unimaginable years (1964-82), on Robben Island, a wind-swept Alcatraz in the bay across from Cape Town. He was as close as it gets to being entombed while still alive. He was permitted only one visitor a year. He was allowed to write or receive just one letter every six months. He did forced labour, breaking rocks into gravel. Little was heard of him, and nothing was seen of him, so that by the time of his release there had been no contemporary photo published of Mandela since 1964; no one knew what he looked like.

Suffice it to say, if most of us were to leave prison after all this, and have it in our power to eviscerate our enemies, no amount of blood would have sufficed. And indeed, many analysts predicted just that for South Africa, as the perilous transition away from apartheid began.

This is the miracle of Robben Island, that Mandela emerged from prison somehow, in some way, an even better man than he went in. Here the personal became the historical. As his rival and sometime ally FW de Klerk has shrewdly judged, his “remarkable lack of bitterness” illuminated and transformed the whole transition process; because no one had suffered more, no one else could call for wholly justifiable vengeance. Only because of his personal miracle was the further miracle of the transition being made without significant violence, repression, or economic collapse, possible.

Mandela matters because what he did (or vitally did not do) was knowable, his grim back-story perfectly understandable; and yet he proved that transcendence – first at the personal level and then, through this, at the global level – terribly rare though it is, remains a fleeting possibility.

Dr John C Hulsman is president and co-founder of John C Hulsman Enterprises (www.john-hulsman.com), a global political risk consultancy. He is a life member of the Council on Foreign Relations, and author of Ethical Realism, The Godfather Doctrine, and Lawrence of Arabia, To Begin the World Over Again.