How the City is trying to bust the ‘myth’ of New York valuations

Bankers and the London Stock Exchange are trying to take apart what they see as a ‘myth’ that firms will automatically fetch a higher valuation when they float in New York, writes Charlie Conchie

When little-known Turkish soda ash firm WE Soda announced plans for a rare float in June, chatter began to hopefully swirl of a potential revival for London’s barren IPO market.

“Green shoots” crept into the lexicon and parched bankers and lawyers looked on with baited breath.

Two weeks later, the dream lay in tatters. WE Soda shelved its plans. Boss Alasdair Warren launched a tirade against London’s conservative investors and slammed the meagre price tag slapped on his company.

New York, he said, offered a “credible alternative” in future.

For many the tale underscored the perennial issue plaguing London’s public markets: firms in the UK just do not fetch the same valuations as New York.

However, moves are being made in the Square Mile to challenge that as received wisdom.

The London Stock Exchange has been on something of a ground offensive to combat the “myth” of a valuation gap with the US this year as it looks to stem the flood of companies away from London to New York.

The bourse has been active in trying to take down the narrative in tech circles in particular, where a healthy supply of big name British tech firms are waiting in the wings for markets to settle before they revive their listing plans.

Neil Shah, the London Stock Exchange’s tech lead, has been “prolific” in courting fintech firms, one fintech chief told City A.M.

“I see Neil Shah at every fintech event going,” said another fintech chief.

Shah insists it has been “business as usual” and his role has involved tackling some of the narratives that have gripped the market this year.

“A lot of our job is debunking myths, such as the valuation, liquidity and research differences between the UK and the US, and also to connect people across the market,” he tells City A.M..

“Then there’s the myth of no tech investors in London. We see investors globally participate in London tech deals, both private and public.”

But the narrative of valuations is a complex one to grapple with. Both the softer mood music and the hard figures in the US are skewed by Nasdaq’s super cap tech stocks, which unrealistically bolster the view of the US as the land of milk and honey.

However, for smaller non-US firms to have listed in New York, it’s something of a different story.

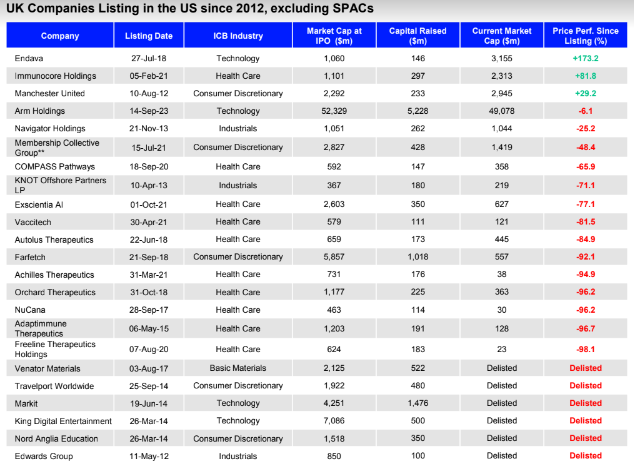

Only 23 UK Companies have IPO’d in the US in the last 10 years. Of those firms, six have already de-listed, 14 are trading down and only three are trading up. On average they’re trading down 43.5 per cent.

Meanwhile, the average price performance of UK issuers who have de-SPAC’d in the US in 2019-2022 is down nearly 90 per cent.

Bankers too have begun to probe the narrative on the suspicion that a mood of doom and gloom rather than hard numbers may be dictating the debate.

UBS has drawn up research in the past month looking to compare like-for-like firms and see whether the story holds up. Their research showed a more muddy and nuanced picture.

US firms do trade at a premium, he says, but it’s nothing like as clearcut as is often believed.

“We’re not evangelists for the UK, we are trying to be balanced and thoughtful,” James Arnold, global co-head of strategic insights and advisory, tells City A.M.

“There are a lot of reasons not to list in the US as a smaller non-US company: these include not getting index inclusion and there is an argument that there is no obvious liquidity advantage. Performance of recent IPOs would support that thesis.”

Comparing firms like BP and Exxon Mobil, and Vodafone and T-Mobile, UBS’s research showed that 55 per cent of US firms traded at higher than a ten per cent premium in their UK listed peers.

However, the rest of comparable firms traded within ten per cent, which Arnold calls a rounding error.

He argues there is also a structural problem in the debate. While the UK might like to compare itself to New York, it would be more useful to look at the US as an anomaly fuelled by its outlier tech giants.

“The debate is framed as the US versus the UK,” he adds. “The debate should be framed as the US versus the rest of the world. And in reality, it should probably be the S&P 500 versus the rest of the world.”

When smaller companies float in New York they face the issue of small fish, big pond. Arnold’s argument is that those smaller names may get a better showing and more love on the London Stock Exchange.

Bankers at Peel Hunt too are asking questions. Analyst Damindu Jayaweera pointed out in September, “high-quality capital will find good-quality companies regardless of listing venue” and tech firms in London do not trade at a notable discount to the US.

In a deepdive on valuations of technology firms across the UK, Europe and US, Peel Hunt found that valuations are “dependent on company performance, and not on the listing venue”.

There are of course still examples to provide the opposing view. As City A.M. noted on Friday, Birkenstock and Dr Marten, two broadly comparable shoemakers have wildly different price tags. Both have revenues just over the $1bn mark but Birkenstock’s circa £6.5bn valuation in New York looks bumper against Dr. Martens’s £1.2bn in London.

But as bankers and the London Stock exchange are starting to point out, those bumper price tags may not be a shoo-in.

Additional reporting by Chris Dorrell