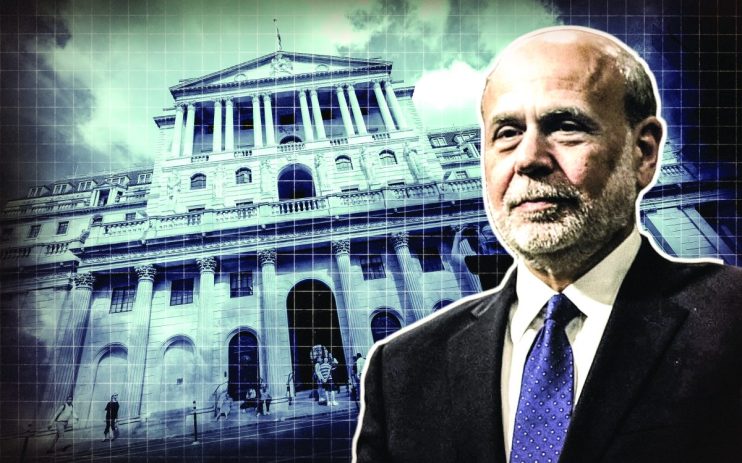

Bernanke is right. The Bank of England must urgently improve its communications

With the Bank of England set to pivot to rate cuts sooner rather than later, it is crucial it communicates its decisions clearly. Failure to do so could further erode public confidence in the Old Lady, Chris Dorrell writes

Ben Bernanke’s long-awaited review into the inner workings of the Bank of England was finally published on Friday.

Alongside Bernanke’s criticism of the processes by which the Bank of England’s forecasts are made, he made a number of suggestions about how to improve communications at Threadneedle Street.

Understandably, these suggestions got less attention than Bernanke’s description of the “significant shortcomings” relating to the Bank’s main economic models, but they are no less important.

The Bank of England received justifiable criticism for its misdiagnosis of inflation as transitory back in 2022 and was eventually forced into a rapid volte-face on interest rates. Bailey himself said the Bank would likely have “communicated our decisions differently”.

One recommendation was that the Bank needed to hire an editor. “The MPC should replace or cut back the detailed quantitative discussion of economic conditions…in favour of a shorter and more qualitative description,” Bernanke said.

It’s a shame this particular suggestion won’t happen before the next MPC meeting in May when it will publish minutes from its latest meeting, its monetary policy statement and a whole new round of forecasts.

That is a lot of material for markets (and journalists) to digest and gives a lot of scope for differing interpretations.

Perhaps more drastically, Bernanke recommended the Bank “de-emphasise” its central economic forecast and embrace scenario-based analyses, in which staff would model the possible impact of different eventualities.

This makes some sense in an increasingly uncertain world, but scenarios could cause as much harm as good when it comes to clarifying communications.

The Bank seems to recognise this. It committed to “reconsidering” the role of scenarios, suggesting it could better help explain divergent views but also noted that the process would have to support the development of a “clear collective narrative”.

It’s easy to see how a range of different forecasts, all modelling different outcomes, could make it more difficult to converge on a single policy path.

This is the problem the Bank of England seems to be facing at the moment and it is likely to cause some big communications headaches in the months to come.

Inflation figures set to be released just a couple of weeks after the MPC’s next decision in May are expected to show that inflation will have fallen below the two per cent target.

Even so, the Bank is expected to leave rates on hold for at least until June, and potentially longer. Markets are now fully pricing in just two interest rate cuts this year with August the most likely start date.

Whatever you think about when the Bank should start cutting rates, there’s no denying that it will be a real issue for the Bank to explain why rates are still at 5.25 per cent – if that’s what the MPC decides – when inflation is below two per cent.

That’s particularly true when the MPC is clearly deeply divided about the timing of the first interest rate cut. Minutes from the last meeting showed that there were “a range of views…on the extent to which the risk from persistent inflationary pressures had receded.”

In recent weeks, Catherine Mann, Jonathan Haskel and Megan Greene have all sounded far more hawkish than Andrew Bailey did immediately after the Bank’s most recent decision.

For Bailey, cuts are already “in play” where Greene thinks they should “still be way off”.

On one level this is to be expected. There is a difficult decision to make, a decision on which, as Bailey has often said, “reasonable people can disagree”.

In the interests of transparency it is good to have those disagreements aired publicly. Public scrutiny of different policy positions should lead to the best possible policy outcome.

The difficulty with monetary policy is that clarity is often seen as the best policy. Giving some degree of certainty to the market is a hugely important part of the Governor’s brief and public disagreements between MPC members over policy hardly makes that task easier.

Indeed, a major justification for central bank independence is making monetary policy as predictable as possible for investors.

With the Bank likely to pivot to cuts sooner rather than later, it needs to be very clear about its preferred approach. Failure to do so could further dent public confidence in the Old Lady.