A history lesson on the Black Death teaches us to resist the urge to panic about Covid-19

When Pope Francis announced the cancellation of major public engagements, his tired face half-obscured by a handkerchief filled front pages across the world — before he headed into self-imposed isolation.

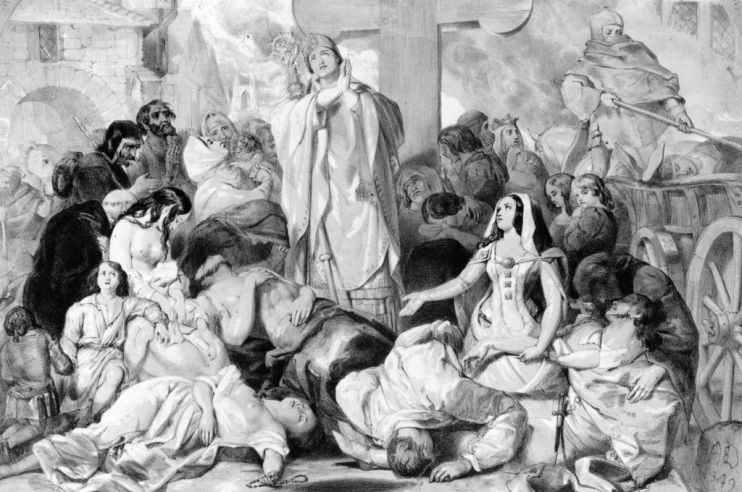

Nearly 700 years ago, Pope Clement VI was trying very hard not to catch a different infectious disease that was then sweeping Europe. Known to contemporaries as the pestilence, modern science has identified it as the yersinia pestis bacterium: the plague.

Clement locked himself in a large stone room with fires roaring either end night and day, and did not come out until it was all over. When he emerged, he found a world in which the graveyards were overflowing. One chronicler said that people were piled up in pits, layered like lasagne.

The plague crossed the channel in 1348 and never left. Once it had finished ravaging Britain, 53 per cent of the population was dead. It would take until Tudor times for the numbers to recover.

Yersinia pestis is the deadliest infectious disease ever to have hit Europe. It had surfaced many times throughout history, but never on this scale. The last major outbreak came in 1665, when it killed 20 per cent of the population. People still catch it today — especially hikers in rural America — but it is now treatable with antibiotics.

Covid-19 is not in the same league as plague. Public anxiety is fuelled because everything we see about it focuses on the fatalities, provoking a crude correlation in our brains’ primitive risk processing centres, leading us to associate Covid-19 with death.

With our risk-fear circuitry only really able to classify dangers into “high”, “low”, or “none”, we assume the worst because we have no personal experience of surviving Covid-19. In comparison, millions survive the flu many times in their lifetimes, so conclude that it is entirely safe, despite it killing up to 500,000 annually.

Our Covid-19 panic is not cost-free. Financial markets have been spooked into costly volatility, wiping real value off pensions and investments. Airlines and other travel businesses are losing critical customers, and a number will inevitably go to the wall as the panic worsens. There will be economic hardships as more people self-isolate and business productivity slows.

But — on a national level — the damage is unlikely to be lasting.

By contrast, the plague of 1346–51 changed Europe’s economy forever.

It decimated the workforce, leading to a critical imbalance of supply and demand. The traditional manorial system collapsed, as free markets for the labour of survivors developed, pulling workers across the country to wherever they could demand the highest wages. King Edward III passed punitive laws to control the rampant wage inflation, but they were unenforceable and failed. The economic power this put into the hands of the poorest was unprecedented — and soon led to demands for political recognition in the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381.

There were many opportunities for the taking, and newly wealthy families and dynasties emerged from the chaos. There were also significant consequences for women. Widows often had to take on their late husbands’ roles. Among the gentry and merchants, this included running landed estates and businesses, forcing legal changes allowing women to be estate managers and entrepreneurs, and permitting daughters to inherit.

The plague killed around 90 per cent of those it infected. Spanish flu — which claimed between 50–100m people after World War One — killed around two to three per cent of those who caught it. Normal flu is fatal for some 0.15 per cent of cases. On current estimates, Covid-19 claims somewhere between normal flu and 3.4 per cent.

This is not even close to the plague, and nor will its consequences be, however much we panic.

Main image credit: Getty