Meet the maritime surveillance chief tackling pirates, smugglers and Red Sea ship attacks from sleepy Bath

Simon Tucker is no stranger to life-threatening predicaments.

Chatting from his offices in sleepy Bath, the boss of the maritime surveillance firm SRT Systems recalls an incident while working in Mexico.

Held up by local police with guns pressed against his back, Tucker looked left and saw his taxi driver make a bolt for it down a nearby alley. “Everyone was speaking Spanish,” he said. “I don’t speak a word, and I was thinking, right, what’s gonna happen?”

“If I hear he gets shot first, I’m gonna leg it that way because then the car is between me and whoever’s shooting, and I hope that he’s a bad shot or I can run particularly quickly, or something like that.”

The language barrier left Tucker thinking his taxi guide had dutifully headed for the hills, but he’d actually been rushing to a cash point after the police told them to cough up. “100 bucks was the price,” he said, and soon they were off on their way.

It is one of a few close calls the eccentric 53-year-old mentions in an interview with City A.M., and his job is certainly different from that of a typical British chief executive.

He runs SRT Systems, an AIM-listed company leading the way in the nascent yet rapidly growing maritime surveillance industry.

A visitor to the firm’s Bath headquarters would be forgiven for underestimating the work done. It is a ramshackle, unassuming warehouse building and some of the rooms resemble more of a workshop than the offices of a cutting-edge tech firm.

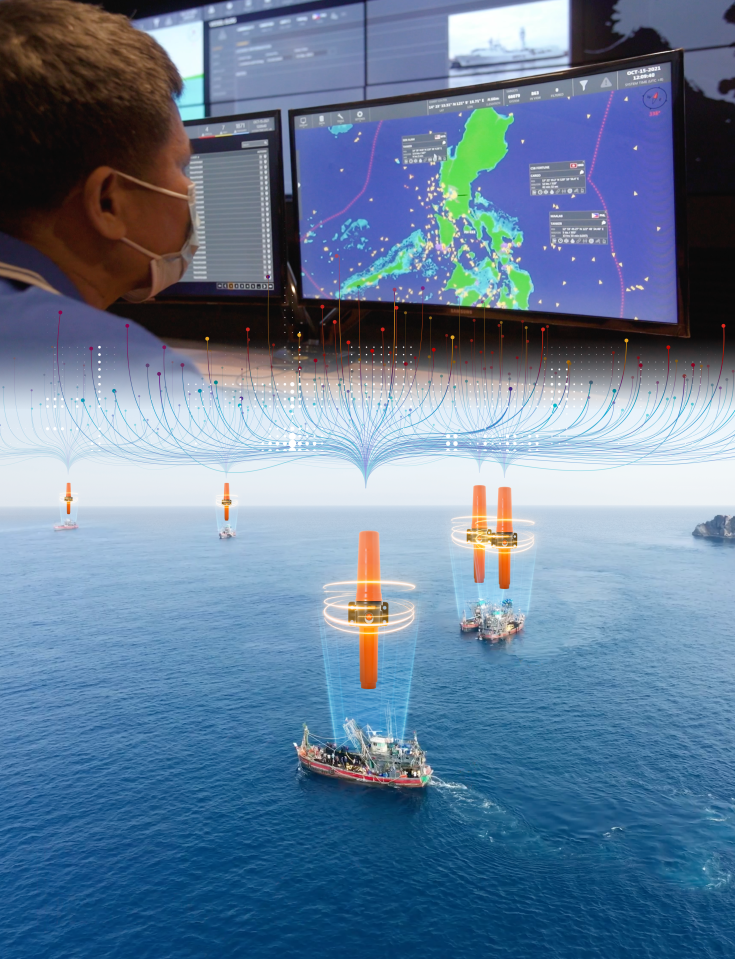

But it is slowly changing the way governments and shipping groups survey the seas, in areas ranging from handling security threats to tackling international crime to managing vast Filipino fisheries.

Founded in 1987, SRT developed its first ship tracker, referred to in the industry as AIS, in 1998. It now sits on the Aim with a market cap of £73m and a forward order book of £160m.

Under 2002 regulations set by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), every vessel over 300 tonnes must have an AIS system to consistently follow its location. However, the devices were often large, clunky and expensive, resembling something of a traditional 1990s computer.

SRT managed to create the modern laptop and microchip-equivalents for the maritime sector, cheaper and niftier, and governments obliged with lucrative contracts.

Since then it has sold anywhere from the Middle East, to Mexico, to Indonesia. Growth and adoption is growing by a quarter a year and there are now nearly half a million of the devices worldwide.

Countries with typically less access to advanced surveillance are now able to get hold of cutting edge tech.

In the Phillipines, one of the company’s longest running contracts, “they are going from a patrol base, going out, stumbling across something naughty, I’ll arrest you, to now I’m going to track you and use AIS to figure out whether you are a threat or not,” Tucker said.

In Indonesia, the coast guard has used SRT’s software to navigate the region’s more than 17,000 islands and catch smugglers using the nearby seas. Tucker himself has been snuck through the country lying on the bottom of a car due to security threats.

“You can imagine the scale of the country, how many miles of coastline…. It’s just wild, huge places and they need to have all that security and systems to deal with it.”

“If you’re down by Papa New Guinea on one of the many, many islands. Who’s gonna detect you in a small boat with a whole bunch of cash?”

As disruption rages in the Red Sea following attacks by Iran-backed Houthi Rebels, security priorities have shifted from the Gulf to the Suez Canal and Tucker told City A.M. the company was working to develop its systems for the region, particularly to combat pirates.

“Once you know what the threat is, it’s a question of do you have a warship there? Or do you need to send a jet or a drone,” he said.

“So you need to track it; you need to make sure you’re not going to shoot innocent people. Because there are lots of people out fishing, waterskiing, scuba diving. Life goes on, the Red Sea is a tourist place.”

It’s not always security, however. The Philippines is the eleventh largest seafood producer in the world and SRT has a contract with the country’s fisheries.

“They’re building their system to monitor and manage their fishing industry, and the reason they want to do that is they want to improve food security, and improve the sustainability of fisheries,” Tucker explained.

The technology allows fishing groups to target areas where the largest catches are. It also keeps track of fishing boats returning to the dock to make the process more efficient.

“So you can fish more efficiently and more effectively and still have your income, and also we know what’s coming back to the dock so we can make sure that the trucks are there, so there not lying on the dock wasting time.”

“They’ve got the first step on that and we’ve delivered that system… It certifies millions, tens of millions of dollars of tuna to be able to be exported to Europe and the United States and places.”

He added: “They are way ahead in their thinking of most countries in the world today in digitising fisheries, and what we have supplied to them is the first step in that.”

Whatever the use, maritime surveillance technology is becoming an integral part of how governments across the globe keep control of the ocean. The global maritime surveillance market was valued at $24.7bn in 2023, and it is predicted to reach $40.3bn by 2030.

Where does that leave SRT? Growing, is the answer, alongside the rest of the industry.

In 2021, the Tel Aviv-headquartered maritime intelligence firm Windward listed on Aim with a market cap of £126.5m, the first Israeli company to IPO in London in half a decade.

Demand is coming from “primarily Asia and Middle East” Tucker said, but some African countries are now enquiring. “We are in discussions with Kenya and Tanzania. We had an enquiry from Nigeria recently, because they’ve got this huge oil theft issue. Bangladesh, the other day, India this morning.”

His job isn’t likely to quieten down anytime soon.