Lessons in wine: Why you should know your terroir

If the clothes make the man, does the soil make the wine? This posit is often made by winemakers, wine lovers and wine snobs alike, all utilising the term “terroir”. But what does terroir mean and does it truly make a difference to wine?

In the broadest terms, terroir describes the unique characteristics of a wine based on its place of origin. This generally includes soil (or “terre” in French), climate, and terrain: think of how a Chardonnay from California can taste completely different from a Burgundian Chardonnay. California’s warmer climate and Burgundy’s stonier limestone soil certainly play a large factor. Even within California, Chardonnays from vineyards grown in the Santa Cruz Mountains won’t taste the same as those from the hot, flat plains.

But this seems too basic. If terroir is only based on sunshine and soil, would a hot year in Bordeaux produce Napa-like Cabernets? Why would wine bars in cities from Paris to New York — not to mention Sao Paolo to San Francisco to Shanghai — name themselves Terroir (or “Terroirs” in London)? And why are winemakers such as Randall Grahm of Bonny Doon Vineyards in California self-proclaimed terroirists?

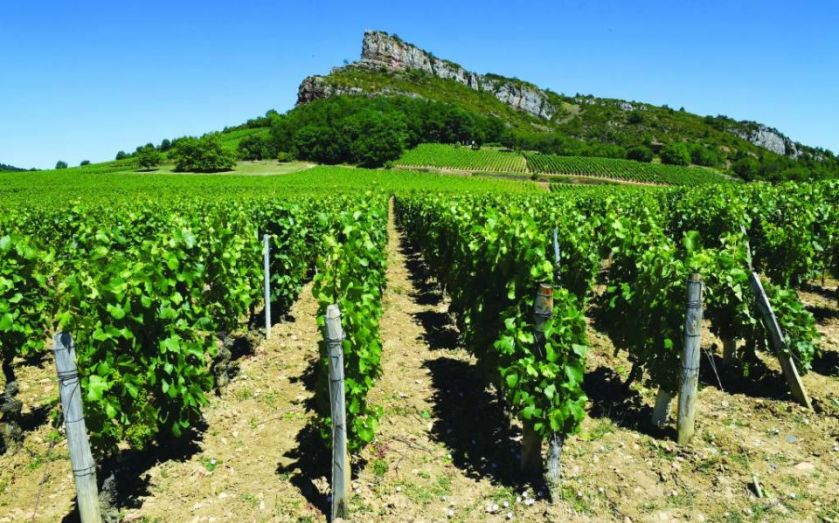

I hate to say blame it on the French, but you can blame it on the French. Perhaps no winemaking region in the world takes terroir as seriously as Burgundy, whose vineyards were hierarchically classified by Cistercian monks in the 14th century. The monks studied viticulture religiously, basing a vineyard’s status on its location and soil type after having noticed that, in general, grapes grown in the middle section of a slope benefited the most from sunshine and water drainage. These often became the Grand Cru (Great Growth) vineyards, with those plots just above or below becoming Premier Cru (First Growth), and those plots on the flatlands or very difficult terrain given a basic “village-level” designation. Soil mattered to the monks, too; there are a multitude of vineyards named after rocks and their various shapes, such as Les Dents de Chien (the dog’s teeth) or Les Caillerets in Chassagne-Montrachet (caille meaning stone).

Of course, the Bordelais couldn’t let their Burgundian rivals have the monopoly on terroir, proclaiming the merits of their gravel on the Left Bank and Graves, and clay marl on the Right. In Napa, one speaks of “Rutherford Dust”, and the best vineyards of Chateauneuf du Pape are known for their large, flat galets, which retain heat and reflect it back onto the vines.

As for me, I am a believer in terroir. I have tasted grapes from vineyards where one row’s fruit tasted completely different to an adjacent row on a slightly higher gradient or with slightly sandier soil. You may even have noticed the effects terroir in your garden or fridge: does one patch of your garden produce better blooms than others? Are Kentish strawberries sweeter than Cornish? Happily, the only way to form a solid opinion when it comes to wine is to drink more.

[custom id=”2″]