IMF warns on unsustainable rising debt burden from climate change policies

Policies to tackle climate change could send debt to unsustainable levels unless governments are able to find new revenue sources, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) warned today.

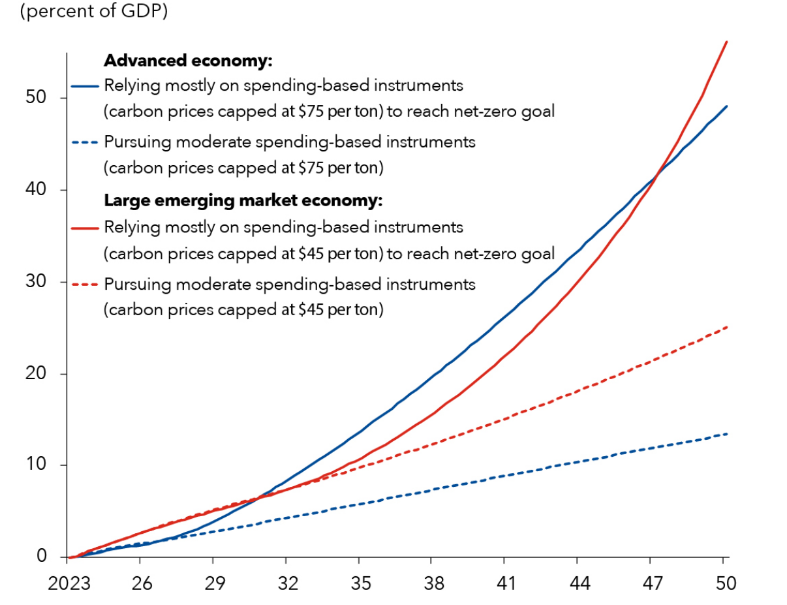

In the first chapter of its Fiscal Monitor released today, the international fiscal watchdog warned relying on government spending to tackle climate change could see debt levels increase by around 45 to 50 per cent of GDP by 2050.

“We consider this to be fiscally unsustainable,” Ruud de Mooij, assistant director in the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department said.

The IMF said governments all over the world are walking a tightrope between achieving climate goals and maintaining fiscal sustainability.

Many measures to cut carbon emissions are extremely expensive, such as ramping up government investment or offering subsidies for renewable energy firms. Governments are also likely to have to increase spending to offset the impact of climate change on the most vulnerable groups.

Debt levels will increase among both developed and developing economies, but the IMF warned that developing economies would struggle to deal with the increase due to higher existing debt levels.

“High debt, rising interest rates and weaker growth prospects will further make public finances harder to balance,” the authors cautioned.

All of this is likely to put increasing strain on public finances. Nevertheless, government intervention was still essential to bring about the scale of emissions reduction to ensure the world reaches net zero by 2050.

The IMF recommended that governments implement more revenue based strategies, like carbon pricing. Carbon pricing measures put a cost on greenhouse gas emissions which are paid for by the polluter.

Such measures would both help reduce emissions, by penalising heavy carbon users, and create a new source of government income.

Postponing carbon pricing would add between 0.8 per cent and two per cent of GDP to public debt for each year of delay, the IMF reckoned.

De Mooij said that proper carbon pricing “steers all margins of behaviour in the right direction, whether it’s investment, whether it’s technological innovation, whether it’s energy saving, we need to get the prices right.”

“The additional benefit is that it raises some revenue. That can be used to relax the fiscal constraints,” he continued.

Increasing the share of revenue measures – like carbon pricing – could dramatically reduce the impact that going green has on public finances, the IMF said. In an indicative scenario, public debt in advanced economies would rise by 10−15 per cent of GDP by 2050 with a higher share of revenue measures.

However the authors suggested carbon pricing may be difficult to implement due to political constraints.

They also said it was “necessary but not always sufficient”, advocating a further mix of policies including subsidies and regulation to encourage the private sector to invest further in green projects.