France is the home of liberalism – it’s high time the country rediscovered this

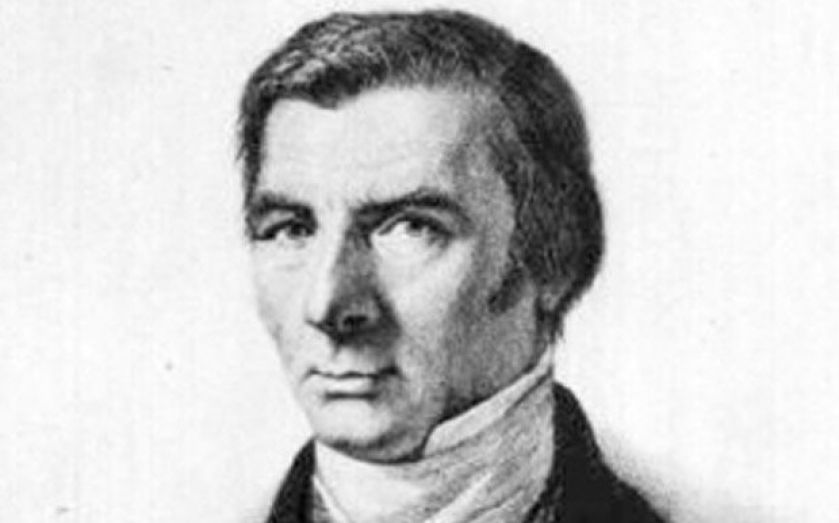

Who wrote that the state is “that great fiction by which everyone tries to live at the expense of everyone else”? Milton Friedman? Ayn Rand? Surely an Anglo-Saxon libertarian? Not at all. It’s Frederic Bastiat, a French economist and politician who fiercely fought the protectionist camp over the liberalisation of the grain trade in the mid-nineteenth century.

Far from being a lone wolf in a country of socialist sheep, he’s part of a French intellectual tradition that runs from Enlightenment philosophers to nineteenth century thinkers such as Alexis de Tocqueville and Benjamin Constant, right up to twentieth century economists and sociologists like Raymond Aron, Jacques Rueff and Jean-Francois Revel.

I would even argue that the French initiated the Liberal school of thought. It is well-known that the idea of protecting individual freedoms owes a lot to the French Revolution. But that also applies to economics.

The French coined the term “liberal”, as well as “laissez-faire” and “entrepreneur”. Adam Smith himself explicitly draws on the French Physiocrats, in particular Francois Quesnay.

Good ideas once led to good practice. France was a highly capitalist country until the end of the 1930s. Electricity and railway companies competed freely, creating the infrastructure now wrongly attributed to public investment. Stock ownership was even more widespread than in the US.

New companies emerged in a business-friendly environment, helped by a political class groomed in the then-free-market Sciences Po college.

But for the last 70 years or so, this tradition has gone undercover. Almost all politicians, chiefly Marine Le Pen of the Front National, blame France’s ills on liberalism – a reviled word.

Intellectuals blush at any association with markets. The French mentality remains defined by a post-war Communist consensus which nationalised vast sectors of the economy, created the public service privilege, collectivised health insurance and retirement schemes, and appointed a “planification minister” – still in many ways a title the current economy minister should bear.

As a result, France has record public spending (seventh in the world), a bloated state (20 per cent of the workforce belongs to the civil service), over-regulation (labour laws now include 12,000 different articles), rent-seeking (Parisian taxis defeated two governments in a row), and constant paternalism.

Our “social model” only pampers bureaucrats and retired baby boomers, feeding a tangible social unease and leading many to seek a better life abroad.

But I remain confident that, under this gloomy surface, things are changing. Civil society activists, techies and entrepreneurs of all hues (over 1m French are self-employed) are building an underground network that will eventually overthrow the old state structures: France is defiant of reforms, but keen on revolutions.

Triggers may be the looming debt crisis, a tax rebellion, or political turmoil created by the predictable victory of a far-right party. Liberals should prepare to seize the momentum and implement radical reforms.

Let France revert to its proper self. Let us prove wrong the cliche of “Colbertism” – noting that Jean-Baptiste Colbert himself, who famously said that a state-owned enterprise not making profit after five years should be closed down, would probably be horrified at the way the country is currently run.