Another LNG-fuelled winter will expose lack of seriousness about UK’s energy goals

Winter is over, with the government managing to stave off blackouts over the coldest months of the year – a real fear that could be seen in National Grid’s own energy forecasts.

Despite the looming risk of a supply crunch, the UK got away with just two national sessions of power saving measures and an evening of coal generation to meet people’s energy needs.

This was courtesy of a remarkable European scramble to save energy, surprisingly warm winter weather, and vast inflows of US liquefied natural gas.

It is this very energy source that the UK will depend on again next winter to keep the country’s lights on and household boilers warm.

UK depends on US LNG to meet energy needs

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and throttling of Europe’s gas supplies, the government is in a challenging position – which it seems intent on worsening.

It has ruled out the prospect of fracking, and is taxing a declining North Sea basin for oil and gas to the hilt – despite the continental shelf meeting nearly half its supply needs.

There is also little short-term prospect of a ramp up in renewables and heat pumps after the underwhelming budget and damp squib ‘Green Day’.

Meanwhile, the UK’s housing stock is 85 per cent heated by gas, and is among the least energy efficient in Europe – yet most the funding pledges to boost insulation don’t kick in until next parliament.

To cap it all, the much touted Rough storage facility, which can store up 100bn cubic meters of gas, is still operating at 20 per cent capacity as an impasse between British Gas owner Centrica and the government over funding persists nearly six months after its reopening.

This means that much like last winter – the UK will be dependent on overseas supplies to meet its energy needs, alongside the luck of warmer weather and the hard work of its allies.

Norway is the largest importer of natural gas into the UK, while National Grid also haggles with European operators for electricity via interconnectors which connect the country with the continent.

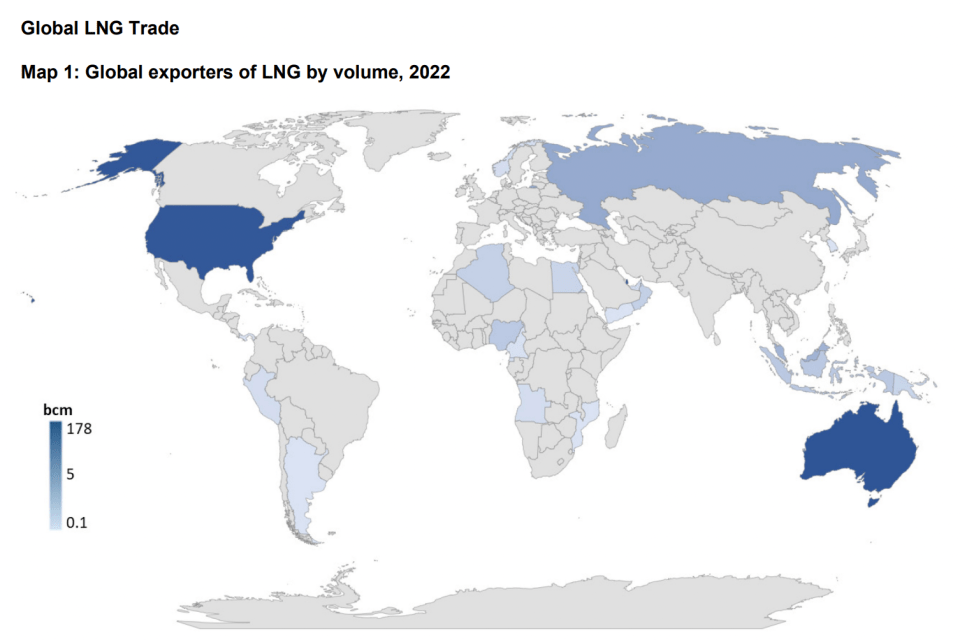

However, the real development last year was the growing reliance on LNG, chiefly from across the Atlantic.

LNG is natural gas that has been reduced to a liquid state, through a process of cooling before it is later converted back into a gas for use.

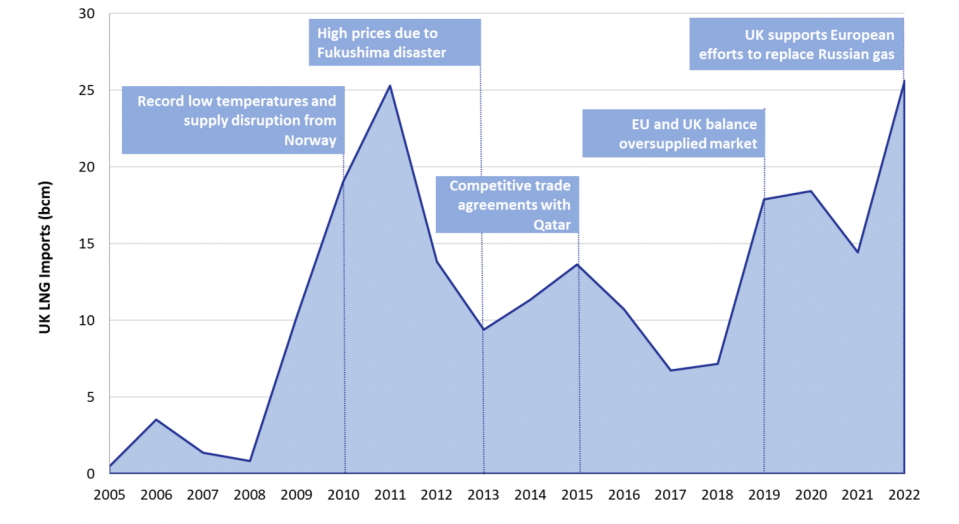

According to the Office for National Statistics, LNG imports to the UK reached a record high of 25.6bn cubic meters, rising 74 per cent on the previous year.

Overall, LNG imports accounted for 45 per cent of natural gas imports across the year, and 35 per cent of demand.

During this period, the US replaced Qatar as the largest trading partner to the UK, supplying half of the country’s LNG imports – helping to power the record profits of Stateside energy giants.

This in turn, helped power Europe, with the UK acting as a de-facto bridge to the continent, as it pivoted away from Russian gas – storing LNG and shifting it across the channel.

No hope for net zero

While it might be practically viable, such a plan undermines the UK’s net zero ambitions and maintains the country’s reliance on costly overseas vendors to meet its energy needs.

Not only are there severe financial implications with the UK coughing up tens of billions to ship LNG supplies in 2022, but the carbon intensity of LNG is staggering.

Gas is as much part of the environmental conversation as renewables, in that if we must depend on it for potentially decades to come, the UK should source supplies with the lowest emissions possible.

However, Rystad Energy has calculated that LNG deliveries into Europe from the US typically have an upstream imported emissions intensity greater than 70 kg of CO2 per barrel of oil (boe) equivalent.

In comparison, piped gas flows into Europe and the UK from Norway has a CO2 intensity of just over 10 kg CO2 per boe, fracked shale gas has a carbon intensity of 13.8kg per boe, and Russian piped gas flows have intensities of around 30 kg CO2 per boe.

This makes LNG more environmentally damaging, to the point its gas supplies even risk being ineligible for repurposing as blue hydrogen later down the line.

These concerns fell on deaf ears last year, when the UK signed a long-term LNG deal with the US – much of which is fuelled by fracked resources, a method banned in its own country.

It is already too late to change matters next winter – but this sustained reliance on LNG has to be a warning sign for the UK, and provide fresh impetus to both push for a renewables ramp-up and to treat domestic gas generation more seriously.

Otherwise, issues as basic as whether we can keep the lights on, heat our homes, or meet our climate goals will be beyond our control – and at the mercy of luck and the goodwill of our allies.