An extract from Spectrum, a new book published in association with the V&A museum about the global history of wallpaper

Before the industrial revolution, the vast majority of domestic interiors were necessarily plain and simple, with whitewashed walls, perhaps tinted with an earth pigment such as ochre or umber.

Fabrics were used sparingly, and were assiduously reused and recycled. Colour schemes were largely drab; jewel-bright hues and rich patterns were delights only available to an extremely wealthy minority.

It’s a far cry from the present day, with digital printing able to reproduce any image in any number of colours on fabric, paper, leather or even plastic. But there are a surprising number of links between designs of the past and the present, with motifs and colour combinations regularly reoccurring, a reminder of how ancient and pervasive are the habits of nostalgic revival and international borrowing.

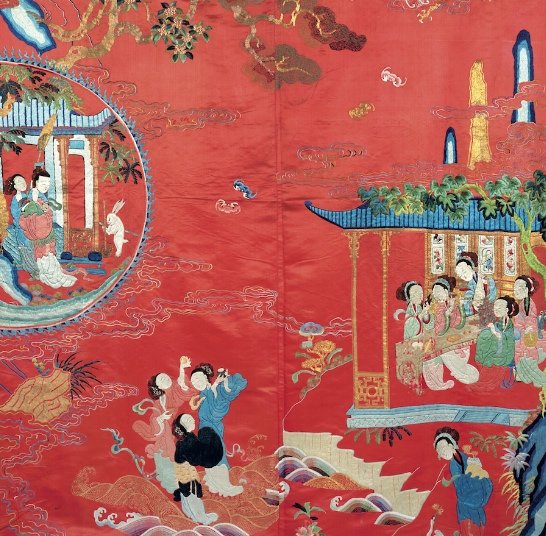

A red silk panel made for an annual Chinese festival in honour of the Weaver Girl

Long before modern globalisation, when communication between continents took months and years instead of microseconds, patterns were being shared and copied. Travelling back through the centuries, what is striking is not so much the progress of history, but its circularity.

Black backgrounds are one of the more noticeable colour tropes, occurring in medieval millefleurs tapestry, 17th-century embroidered hangings from Turkey and a Walter Crane wallpaper from 1897. Equally apparent is the enduring popularity of red and green as the dominant colour theme of a design.

Travelling back through the centuries, what is striking is not so much the progress of history, but its circularity

Fashion does intervene, of course, as in the mid-18th century craze for chinoiserie, or the changing collective taste for rooms that are either busy or sparse, affecting how much colour and pattern is seen as elegant and desirable. The trend towards abstraction in designs for interiors is clear in the wallpapers from the first decades of the 20th century.

Fukusa, a textile cover that's traditionally draped over gift boxes in Japan

Culture and religion also have their part to play, whether the Islamic tendency to exclude images of people and animals, or in the symbolism of the natural world that is integral to the aesthetic of Japan. Even tax has its role: heavy duties, such as those imposed in 18th-century Britain on wallpapers, chintzes from India and woven silks from France among other things, made these items more rather than less covetable, their expense equated with luxury and exclusivity.

Over the centuries there have been various concerted attempts to suppress pattern and colour. The Puritans finished the job of whitewashing richly decorated church interiors that had begun in the Reformation. More recently, modernism, with its disapproval of ornament – ‘a needless expression of degeneracy’ as Adolf Loos so tartly put it – has successfully disseminated its doctrine of white walls and straight lines.

Fortunately there is something joyful and life-affirming about colour and pattern that refuses to be quashed. They keep bobbing up again, catching our eyes like twinkling lights in a dark sky, intriguing our brains.

Spectrum: Heritage, Patterns and Colours is out now, published by Thames & Hudson in association with the V&A