The Tories risk becoming an irrelevant party in the capital

The decision to postpone May’s London mayoral election a full year due to the coronavirus pandemic offers an opportunity for parties to reflect on a to-date lacklustre campaign.

For the current mayor Sadiq Khan, generally good poll ratings have sat uneasily alongside persistent questions about seemingly out-of-control knife crime, the long-delayed completion of the new Elizabeth line, and the shortfall between rhetoric and reality on action to solve London’s housing crisis.

The mayor’s reluctance to attend hustings and debate — a failing shared with Tory candidate Shaun Bailey — has been a disservice to Londoners who may not attend these, but might like to learn about what transpired, in City A.M. and elsewhere.

But while Labour’s mayor has had his issues, the other main parties have theirs. Bailey polls well below previous Tory candidates, while Siobhan Benita isn’t holding onto Liberal Democrat supporters tempted by either the mayor or independent Rory Stewart, according to the latest Queen Mary University of London’s Mile End Institute poll.

The Lib Dems have been badly squeezed the last two mayoral elections, earning only four per cent of the vote in 2012 and five per cent in 2016 — both times finishing fourth after the Greens, who are currently polling better than any previous mayoral contest. But the Lib Dems’ flatlining is arguably less serious than the Tories’ predicament.

Tory support in the race for City Hall has been in steep decline for years. Steadily increasing under Steve Norris then Boris Johnson, backing for the party’s London mayoral candidates fell sharply from a 44 per cent peak in 2012, to 35 per cent for Zac Goldsmith in 2016. Now Bailey polls only 24 per cent in last week’s poll, lower than every Tory performance since the mayoralty began 20 years ago.

This precipitous drop is part of a wider Tory London problem. December’s General Election left the party holding just 21 constituencies in the capital. Only in the wake of Tony Blair’s landslides was it lower. But this time, a dismal showing in the metropolis occurred as the Tories stormed home to an 80-seat majority UK-wide.

In prosperous, professionally middle-class Putney, Labour had its only gain anywhere in the nation that December night. Cities of London and Westminster, a central London constituency that includes many of the nation’s landmark tourist destinations and super-wealthy Belgravia and Knightsbridge, saw voters swing 13.2 per cent from the Tories to the Lib Dems. In once-safe Wimbledon, which neighbours Putney, the Tory-Lib Dem swing was 15.4 per cent.

In more downscale London further east, the Conservatives gained at Labour’s expense. Traditionally an electoral desert for the party, three seats illustrate its improving fortunes there: Romford, Dagenham & Rainham, and Barking all chalked up Labour-to-Tory swings of around five per cent on election night.

Another statistic sticks out. In that latter trio, the share of university-

educated voters lies between 18 and 22 per cent. In the former three, graduate voters comprise between 52 and 55 per cent of the electoral roll. In December’s other Tory loss besides Putney: Richmond Park to the Lib Dems, the figure is 55 per cent.

What has changed really since 2016 is that a Tory offer centred 10 years ago on economic aspiration and social liberalism has been infused with a strong dose of populism. Once, Tory voters in the capital could rely upon the party’s support for the City of London and its access to the vast EU internal market; free movement, with its reciprocal rights to work, live and study across the continent; and fiscal responsibility on government spending. That era is now over.

Elsewhere, hollowing out the affluent, educated urban Tory vote to attract traditional Labour supporters with an appeal to nationalist, anti-immigrant sentiment coupled with busting the government’s budget might work. In London, however, cosmopolitan graduate high-earners form a higher electoral share. Similarly, talk of “levelling up” the regions doesn’t offer much to the capital, which disproportionately pays the nation’s bills and has its own problems and deprivations.

In a city where two thirds of voters backed pro-referendum parties only last December, and six in 10 voted Remain in 2016, the party’s three shortlisted candidates were all Brexiteers. Instead of running a distinctive, independent-minded candidate, free to deviate from the national line, as in past elections, and choosing to lean toward the electorate, Tories chose among policy carbon copies.

London Tories show signs of entering a vicious circle whereby poorer electoral returns lower the quality of candidates applying, making the party still less electable. The party has gone from Norris (who had been transport minister and an MP), to Johnson and Goldsmith (who were at least MPs), to Bailey, who was a youth worker.

With a year to go in the race for City Hall, an incumbent mayor well ahead in the polls, and a fresh new independent face in the form of Rory Stewart, are the Tories becoming irrelevant in the capital because they no longer speak the language of Londoners?

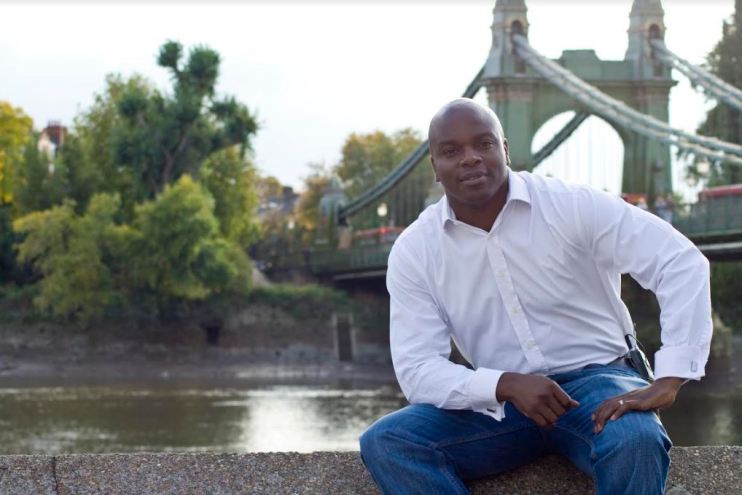

Main image credit: Getty