Interest rate hikes risk a household debt tragedy if we don’t act now

Beware the economist bearing forecasts. The only thing that’s ever certain about economic predictions is that they’ll turn out to be wrong. But this one’s nailed on: interest rates are going to rise. Hardly the riskiest punt – the current emergency base rate of 0.5 per cent can’t be sustained forever and, as yesterday’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) minutes confirm, the question is when and how fast, not if.

And yet despite everyone knowing what’s coming, we appear under-prepared for this inevitability. The slashing of mortgage rates in recent years has generated huge windfalls for many families. But the pressures of unemployment, under-employment, falling real wages and welfare cuts mean that some pre-crisis borrowers have found that the recent past has provided a breathing space without allowing them to get to grips with their structural affordability problem. Even with rates at an historic low, almost one-in-five mortgagor households say they’re struggling to meet their monthly repayment.

With the recovery taking hold and employment continuing to grow strongly, the default option is to simply allow all of this to unwind itself naturally. After all, interest rates are set to rise gradually and are expected to reach a “new normal” of 3 per cent over the next four years – hardly extravagant by historic standards. There will be casualties, yes, but that’s a normal part of any credit cycle, isn’t it?

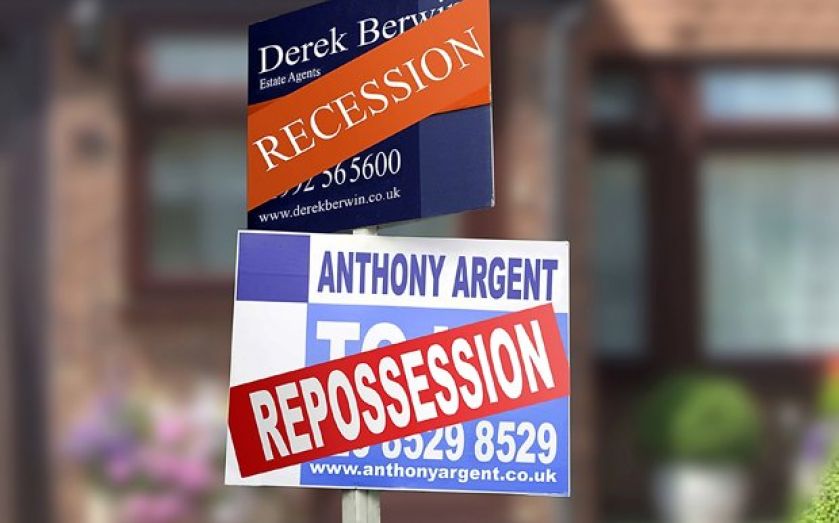

But we’re not just talking about a handful of families: the pain could be sizeable. Indeed, the risk is that the fall-out has the potential to feed back into the aggregate outcome. Our modelling suggests that just over 1m households are already “highly geared” – spending more than one third of their net income on mortgage repayments – and that number could more than double by 2018. That means subdued spending and a drag on recovery. Where repayment difficulties morph into repossessions, it means wider economic and social upheaval, alongside a rising housing benefit bill for the government.

Absent broadly-based growth that feeds into improvements across the income distribution – an unlikely scenario given current prospects for pay growth and plans for more welfare cuts – there is no costless solution.

Today we publish Hangover Cure, our assessment of what a managed approach to this problem might look like. We identify three broad steps: maintaining the current window of opportunity afforded by low interest rates until there is evidence of sustained growth in household incomes; making the most of that window by preparing borrowers for the change that is to come; and improving the safety-nets available to those who can’t avoid falling into some form of debt crisis.

The MPC has been very clear about its intention to remain sensitive to the sustainability of household income growth in its future interest rate decisions, but the measure it uses to gauge that growth is misleading. It consistently over-states the pace of growth relative to better – but much less timely – measures, and it provides no means of understanding what is happening at different points in the income distribution. The MPC is being asked to steer a difficult course with a malfunctioning dashboard. This needs to be fixed.

Whatever it bases its judgement on, the MPC will eventually push rates up. We need to do more today to prepare borrowers for that change – prodding them into action and pointing them in the direction of help where appropriate. Yet some will find their ability to take evasive action restricted. For these “mortgage prisoners” – who find themselves excluded from new deals by today’s tighter lending criteria and so remain parked on their existing lender’s standard variable rate – the regulator must provide better protection.

Ultimately, some borrowers will find they are best served by exiting the housing market. Gradual rate rises mean that the crunch point for such households may still be several years away, but it is right that we act now to improve the availability of safety nets designed to ease such transitions. The government has committed funds to help new buyers onto the housing ladder; it should also stand behind those at risk of falling off. Our “help not to be repossessed” proposal involves home owners selling a stake in their property in order to reduce their monthly housing costs – a form of shared ownership in reverse.

In the run-up to next year’s election, the parties are busy competing on who is best placed to deal with the deficit and the squeeze on living standards. But with the base rate expected to rise six-fold over the first half of the next Parliament, they are strangely silent on how the household debt overhang might be approached. If they don’t rectify this blind spot, my forecast is that they – and we – will regret it.